RAPID CITY, S.D. – Isolating herself from family after her Covid-19 diagnosis on the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation, Sicangu Lakota great-grandmother Cheryl Angel found little choice but to traipse from one lonely hotel room to another for shelter.

Angel, a veteran Water Protector and self-described Sacred Activist, vowed that if she survived the deadly contagious disease, she would do all in her powers to assure others receive better access to treatment than she did.

So, she was gratified when her post-recovery efforts succeeded in helping Camp Mni Luzahan conduct an unprecedented community-based Covid-19 health testing Nov. 13 for ‘houseless” relatives sheltered at its tipi circle here in the heart of the Great Sioux Nation’s indigenous treaty land.

Volunteers at Camp Mni Luzahan (Lakota for “rapid water”) conducted an unprecedented community-based Covid-19 health testing Nov. 13. COURTESY / Cheryl Angel

“This is what I envisioned when I was sick, alone, near death and couldn’t breathe,” she said. “Our tribe didn’t have anything set up, and if it weren’t for my relatives, I would have died in there,” she told The Esperanza Project.

Angel’s family members made two-hour drives twice daily to leave breakfast and supper outside her impromptu isolation wards, while inside she followed instructions to use a steroid inhaler four times a day and learned to shoot herself with an epinephrine injection when she felt faint.

She managed to keep her lungs from clogging with phlegm by running hot water in the shower to make a steam chamber and repeating a series of exercises “to get the goo off,” she recalled.

“My prayer was that, if I ever survive this, I’m not going to let anybody else be alone in a hotel room.”

She wouldn’t stay at her rustic Rosebud dwelling because two household members had pre-existing health conditions. “Access to running water and private bathroom facilities is absolutely necessary to recover and to contain Covid-19 from spreading,” she recognized.

“The tribe didn’t have a safe or adequate quarantine area able to provide Covid-19 support,” Angel told The Esperanza Project. So, she said, “I left the reservation.”

She alternately stayed in Valentine, Neb. and Kadoka, S.D., as room bookings permitted. Switching places, she said, “At one point, I was so weak I could barely walk.” However, she added, “I know I wouldn’t have survived on the reservation. Like my son, I probably would have been flown out. And who knows if I would have survived that.”

Weeks after Angel recovered, her son and fellow pipeline fighter Dale “Happi” American Horse, 30, received a Covid-19 diagnosis for severe symptoms when his brother rushed him from their home to the Rosebud Indian Health Service emergency room, just in time to be saved by a life-flight bound for a private hospital in South Dakota’s largest city of Sioux Falls.

Angel recounted that the brother, her younger son Elias American Horse, had tested positive eight days earlier, but didn’t know it because the Indian Health Service protocol was to wait a week before releasing Covid-19 test results.

An employee later told Angel the results were back from the lab the day after the test, she said. If she only could have had them, she could have administered the same Native herbal remedies she used to alleviate her symptoms before Happi’s condition became so severe, she lamented.

By the time of his emergency, Angel was in Rapid City working with a host of local grassroots organizations advocating for treaty land rights restoration and for people extremely vulnerable to the coronavirus, as they set up Camp Mni Luzahan to harbor underserved or homeless relatives without the constraints of pre-existing government and private agencies.

Wearing PPE attire facilitated by Hesapa Voter Initiative, Cheryl Angel administers a nasal swab Covid-19 test to a Camp Mni Luzahan participant, in community-wide grassroots effort. COURTESY / Camp Mni Luzahan

“Unhoused relatives have underlying issues,” said Minneconjou Lakota camp organizer Jean Roach of Rapid City, explaining the need for a grassroots mutual aid effort, despite existing services. Some Native community members in the independent movement dislike the label “homeless” because it “sounds institutional,” she explained.

She and Angel were among the first to set foot at the camp, which relocated in tribal government jurisdiction on the outskirts of Rapid City two days after police raided its original site in town. Angel lit a sacred campfire and put down a tobacco offering to keep the flames alive, as the snowy season began Oct. 18 here in the Black Hill.

Jean Roach, among the first to set foot at the camp, prefers the term “houseless” to “homeless” because it “sounds institutional.” COURTESY / Lloyd Big Crow Sr.

The camp crew convinced the nearby Oyate Health Center, a tribally-owned primary care clinic, to send a Covid-19 testing team on Oct 23, resulting in the discovery of nine positive cases at the group living site.

The crew moved the diagnosed to private quarantine lodging paid initially by the non-profit Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Health Board, which oversees the Oyate Health Center, and subsequently by the South Dakota state government.

Coordinating the grassroots pandemic response there as a volunteer, Angel supervised the quarantined camp members in chores of maintenance and sanitation.

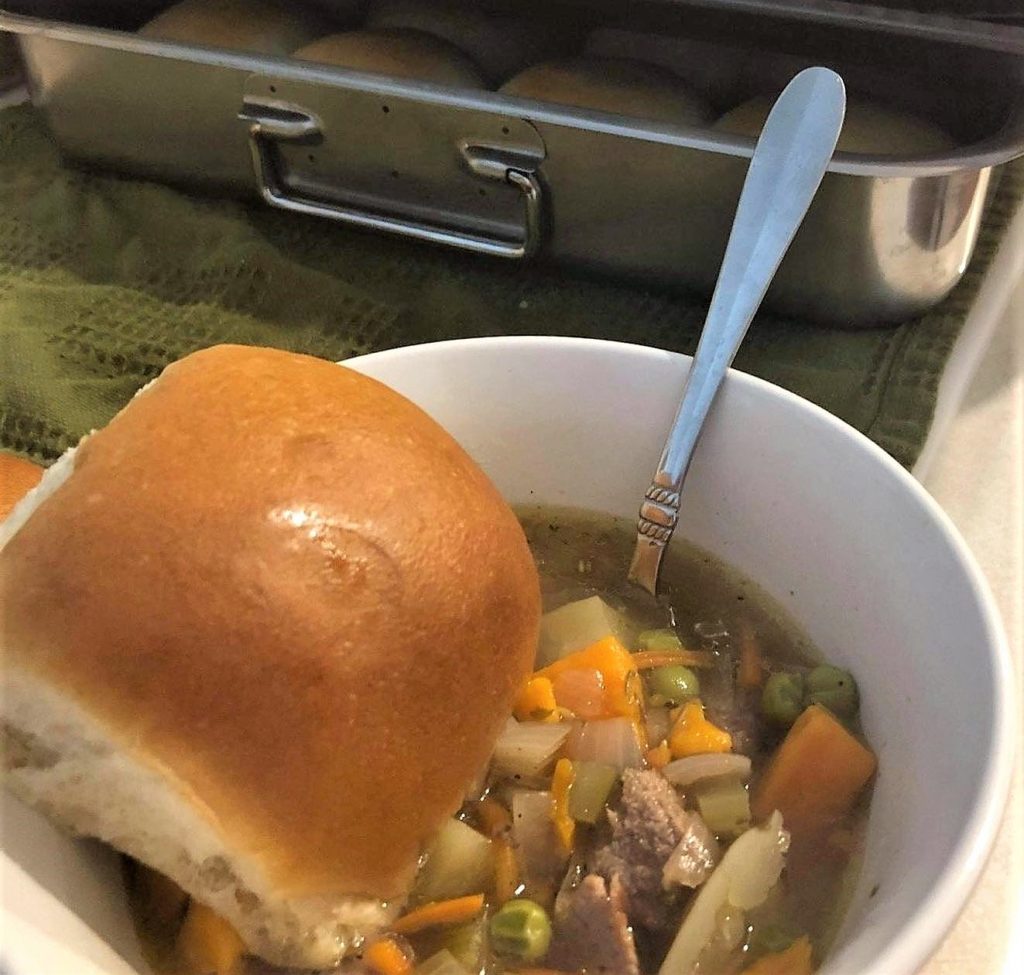

A mutual aid initiative fed them through Meals for Relatives Covid-19 Rapid City Community Response, which gathers donations, marshals chefs, and delivers home-cooked food.

Beef stew and dinner rolls prepared by Bobbi Jean Jarvinen for Camp Mni Luzahan. Courtesy photo

Meanwhile the Covid caseload in the state was burgeoning, and the camp lobbied the Oyate Health Center for retesting at Camp Mni Luzahan after the 10-day minimum quarantine period.

Although that protocol is not required for medical release in South Dakota, Angel said, “I wanted to retest everybody because it’s a vulnerable population going back to camp.”

The tribal health administration ramped up to create an emergency operations center, calling the lodge twice daily to check on needs of the quarantined, then delivering masks, medical packs, snacks, and cleaning supplies, as well as providing clinic transportation and contracting providers of catering, bedding change and security services.

However, the Oyate Health Center stopped short of agreeing to send another team to the camp to retest. So, Camp Mni Luzahan participants sought to take control of testing on their own.

On Oct. 30, Angel had met Dave John, a Tewa and Diné organizer from Peaceful Advocates for Native Dialogue & Organizing Support, PANDOS, when he was delivering an army tent that the Salt Lake City-based group raised money to purchase for the kitchen at the camp. By that time, the camp had more than tripled in size from its first four tipis.

Camp Mni Luzahan has more than tripled in size from its first four tipis. COURTESY / Mni Luzahan Creek Patrol

John works for ATL Technology in Springville, Utah, which makes cables, connectors, medical devices, and pandemic test kits. PANDOS, which does fundraising in order to purchase the Covid-19 test kits, purchased thousands of test kits to donate, too.

The non-governmental organization supports work to raise awareness on Native issues spotlighted internationally during the 2016-2017 mobilization at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline construction without indigenous consent across unceded 1851 Ft. Laramie Treaty territory.

PANDOS purchased thousands of the Covid-19 test kits to donate. COURTESY / Dave John

John dropped off the free nasal swab test kits at the camp and told Angel of his Zuni Pueblo and Diné partner Allen King, executive director for American Indian and Alaska Native Development at NextGen Laboratories, which is an accredited and certified Covid-19 test provider.

The two men had hooked up earlier this year with plans to go to the aid of the Southwests’ Navajo and Pueblo Indian populations, among the hardest-hit by Covid-19 due to lack of access to services.

However, as if that wasn’t a daunting task in itself, the partners soon found a lot wider demand. “Things moved a little bit faster than expected,” John told The Esperanza Project.

Soon they were not only testing the Navajo Nation Police in Window Rock, Arizona, but also the remote Navajo Mountain population of the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe in Utah, as well as patients at the clinics operated by Native Health of Phoenix, one of the largest urban public health care programs in the country.

“I’m glad we teamed up,” King told The Esperanza Project. The purpose is not to compete with urban or treaty-based Covid-19 care providers, such as the Indian Health Service and tribal governments, but to fill gaps they cannot, he explained. “We want to help all the tribes. We know that will take time, but our focus is the underserved,” he said.

After Angel contacted King and found his company willing to provide free laboratory testing for the camp in the Black Hills, she said to herself, “We’ve got a supplier and we’ve got a lab. What else do we need?”

Allen King (left), Cheryl Angel (center) and Dave John (right) vow to fill gaps in access to Native protection from pandemic. COURTESY / Dave John

That turned out to be a medical provider who would vouch for the training and reliability of a community-led process. It was almost a deal breaker.

Angel initially obtained Oyate Health Center Chief Medical Officer Dr. Mark Harlow’s acquiescence, however, he said he would not have authority by the date scheduled for testing. Another doctor at the area’s largest private employer, Monument Health, reneged the day before the scheduled event.

“I said, gee, I’m going to really pray,” Angel recalls. So, she “went to the fire” at the camp. Having traveled in India and Mexico carrying a staff for global indigenous unity, she recalled how cultures far and wide use fire in ceremony, and she convoked the relatives to pray with her.

“I told them this fire is listening to you. If you have anything you can’t say to your fellow man, you can say it to the fire. It can heal and protect us just like air and water,” she said.

In fact, a number of people who frequent the camp had already healed to the point of taking sobriety pledges, and that evening they agreed to work as volunteers to help make it a haven for others in need, participants recounted.

Just as John and King were arriving in Rapid City, Angel received a phone call from Creekside Medical Clinic owner Dr. Nancy Babbitt, who had been informed of Camp Mni Luzahan’s predicament.

Babbitt stepped up to the plate in the nick of time. “I was really excited,” she told The Esperanza Project. “If we can use non-medical people and train them, this is one of the ways we can reduce the spread of this disease,” she said after signing an agreement with NextGen Laboratories.

“My experience dealing with Covid-19 in South Dakota is one of failed leadership. Our governor has made it clear it’s up to the people, so we have to come up with creative ideas to help stop the spread of the corona virus,” she added.

Joining John, King, Angel and others at the camp, Babbitt verified their training and cinched the testing of 14 volunteers and guests on the scheduled date.

“They did a great job. They had all the right equipment, and everything was done perfectly,” Babbitt confirmed.

Joining Allen King (left), Cheryl Angel (right) and others, Dr. Nancy Babbitt verified their training and cinched the testing. COURTESY / Camp Mni Luzahan

“When I saw what was happening at the camp, it filled my heart – to see people making a difference to the population there needing access,” she said.

“Safe quarantine is a luxury, especially if you are homeless,” she emphasized.

King verified that the test kits had been received and analyzed in California, then the confidential results were made available to the designated camp trainees by the end of the following day. All 14 came back negative.

He shared in the emotional response of “just being out there and seeing the amazing work they’re doing, like when a resident gets sober and joins up to help out at camp with the work.” The effectiveness is based on building trust through mutual aid, he observed.

“The camp organization is something that’s needed; not only for homelessness, but also for sobriety,” he observed. “It’s a lot of things combined.”

The camp is an outgrowth of the Mni Luzahan Creek Patrol, a Native grassroots watchdog for the at-risk community members who congregate along the banks of Rapid Creek, where it runs through Rapid City.

Participants rescue them from precarious circumstances that frequently end in tragedy, the most recently recorded being the police identification of a man’s body found unattended on the creek bank the day before testing at the camp.

Keeping the patrol, the camp, the meals, the sobriety, and the testing in the hands of Native community members is “innovative and grassrootsy,” but at the same time it’s all part of the promise forebearers made to keep the peace when they signed the treaties, Angel notes.

“I really believe in the treaties, putting down weapons and living in peace. That means we provide our own health care and education. We protect our water from gold and uranium mining, gas and oil companies,” she said. “They entered the treaties to protect the land and the people.”

Talking to relatives in camp, she said, “It’s a wonderful story about regaining our sovereignty.”

Roach said the camp organizers would like to offer testing to every new camper each morning and, “One thing about us is we can do it because there isn’t a boss to say ‘no’.”

John and King foresee the day when the camp trainees can use their companies’ free supplies to conduct mobile mass testing, not just at the camp but on hard-to-reach rural Indian reservations across the Northern Great Plains.

“So many people are dying every day with the misinformation and the dumb rules that they make,” Roach bemoaned. “It really feels good that these tests would be available in other communities.”

Contacts:

Mni Luzahan Creek Patrol WEBSITE

Mni Luzahan Creek Patrol FACEBOOK

Pandos.org FACEBOOK

Pandos.org WEBSITE

Meals for Relatives – COVID-19 Relief in Rapid City

This story was reported and produced with the generous support of the One Foundation.