As I toured the Matamoros refugee camp for the first time, all my questions received the same answer:

Who built the showers? Tucker.

Who put in the water filtration system? Tucker.

Who dug the drainage canals? Tucker.

When I asked where to find this Tucker, the answer was also the same: in the camp.

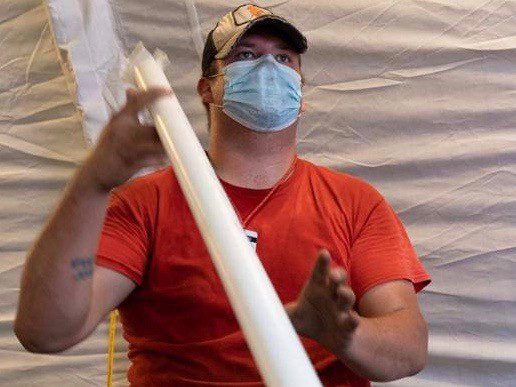

Brendon Tucker constructing hand-washing stations in Matamoros refugee camp (Courtesy/Brendon Tucker)

But with 2,500 asylum seekers plus doctors, nurses, and volunteer humanitarians — both permanent and visiting — I decided tracking down a mystery man would be like looking for a needle in a haystack. So I went to interview the grassroots emergency medical providers at Global Response Management (GRM), instead.

While waiting, I claimed an empty camp chair in the outdoor carpeted courtyard between GRM’s mobile clinic and examination rooms created from IKEA Foundation “Better Shelters.” Used around the world as temporary housing in refugee camps, I wondered why here there were only three.

In Matamoros, refugees live under tarps and tents. It was lovely and cool in the shade of the trees. Even in January, the sun beats down hard on the Texas/Mexico border at the height of the afternoon. Out of the sun’s glare, I felt slightly sheltered, too, from the dust kicked up by passing supply trucks, foot traffic, and children’s soccer games. It hadn’t rained in Matamoros for weeks. Dust hung in the air and lodged in the lungs. The most common health complaints presenting at the GRM clinic at that time were respiratory-related illnesses.

I struck up a conversation with three other people taking a mid-day break. They wore t-shirts and jeans splattered with mud. A svelte, long-haired brunette women with gorgeous teeth that peaked out from behind a shy smile leaned familiarly against an equally lithe man with curly locks and curiously cloudy blue eyes. His hands draped one on top of the other over the handle of a cane. It was the cane of an older person — nothing fancy — but it did make me wonder if he was blind.

The third, a young, ruddy-faced man with an easy smile and an infectious laugh, took up more space than the other two put together. When they spoke, I had to lean in to hear. When he spoke, I sank back into the canvas embrace of my camp chair and let his accented drawl wash over me. It wasn’t too dissimilar from my Tennessee twang. Still, I couldn’t place it. As we chatted, I struggled to guess his age, unsure if the layer around his middle was a pre-mature beer belly or persistent baby fat that refused to be shed.

One thing was certain: he was a hard worker. The baseball cap slung, brim-backward, over his head was stained with grime and dried sweat. It turned out the three were cleaning the river bank that day. I was just about to ask how one negotiates a steep embankment while wielding a cane when someone called out, Tucker! All heads turned.

“If it weren’t for landing in jail, I’d be dead today.”

Brendon Tucker in Matamoros, Mexico with (left to right) Dr. Melba Salazar-Lucio of Team Brownsville and Joyce Hamilton, Elizabeth “Lizee” Cavazos, and Cindy Candia of The Angry Tías & Abuelas of the RGV (photo courtesy of Cindy Candia)

Whatever I was expecting, Brendon Tucker was not it. A young man with a big presence in the Brownsville/Matamoros humanitarian community, he’s the Angry Tías favorite nephew and Team Brownsville’s prodigal son; the backbone of GRM and the right and left hands of Resource Center Matamoros (RCM). While only 25, his journey here is fascinating, for Tucker was brought up on a diet of right-wing media and racist bile.

Tucker, as he is affectionately called, hails from the geographical mid-point between the American Southeast and Southwest: Texas Hill Country. Known for its tall rugged limestone and granite hills, beautiful lush valleys, mystical underground caverns, and Canyon Lake — where Tucker grew up — Hill Country is a popular get-away destination from both San Antonio and Austin. It is home to wealthy ranchers and struggling farmers, many that have been there for generations, as well as its newest arrivals: heat-seeking retirees.

It is also very white. While once populated by mavericks — German immigrants who opposed slavery and stood against Texas secession during the US Civil War — Hill Country today is one of the reddest regions in one of the reddest states, where Hillary Clinton claimed only 27 out of 254 counties in the 2016 presidential election.

“I grew up politically conservative because that’s what I was taught,” states Tucker. “In history class we watched the O’Reilly Factor every day.”

Tucker was a troubled kid. He lost his mother when he was 12 and, being naturally hyper-active with ADHD, he never had much use for school.

“I was a little shit. A redneck brat from a redneck town in a redneck state.”

As a teen, Tucker was traveling a destructive path. At 17, he was caught with enough weed — .2 grams — to land him a 90-day jail sentence or probation and a stiff bail. No one posted bail, so Tucker did the time.

On the inside, he cleaned up — marijuana wasn’t the only thing he’d been using — and he discovered Stephen Hawking and a love of reading. He also learned first-hand about the racial injustices baked into the US prison system.

How the Other Half Lives

Out of jail, he moved to Houston for rehab. There, he lived with his paternal grandmother, who he credits for saving his life. Paraphrasing “the great Cornel West,” Tucker’s emphasis, he states: “I am who I am because she loved me, she cared for me, and she attended to me.”

But with a Class A misdemeanor on his record, he had a hard time finding a job with any future. During his three years in Houston, Tucker lived how too many live in the so-called Land of the Free: juggling several minimum-wage jobs — none with health care — and still barely making ends meet. He bounced from one gig to another at Ross, Sunglass Hut, Kate Spade, Starbucks, and for a time, he rented short-term furnished apartments to families of cancer patients receiving treatment at the Houston Medical Center.

One day, Tucker found some of his previous tenants living in their van. They were paying for their relative’s cancer treatment out of pocket and had run out of money. Also about that time, he met a homeless guy, living under a Houston bridge. He was dying of stomach cancer, unable to afford treatment at all. Meanwhile, it was not unheard of for Tucker to sell five pairs of the same designer sunglasses to a single client — one pair for each boat and car.

“That’s when I discovered income inequality and the broken state of health care in the US.”

That’s also when Tucker woke up to his own privilege as a white person, even a poor one. Working at Ross “Dress for Less” discount store, he got promoted after only a couple of months, in lieu of black co-workers with degrees and kids who’d been there longer. He witnessed shoppers use the “N-word” with his black colleagues, reducing them to tears. One ‘Karen’ accused a black fitting-room attendee of stealing her purse and called the cops. Even they refused to believe that after stepping out to grab another item, she’d returned to the wrong room until Tucker pointed out the woman’s mistake.

Sergio Cordova and Brendon Tucker, taking a break from cooking in the alley behind the apartment that housed the Team Brownsville Kitchen for Asylum Seekers (photo by Carlos Grana, Peruvian-American film director, 2018)

Steering Toward a Career in Direct Action

The 2016 presidential election brought politics into Tucker’s life. After a brief stint in Austin, living with a bunch of “radicalized lefties,” he went home to help his dad fix up houses and manage the family Sno Cone business. There, Tucker tuned out the typical radio voice of the construction site — Rush Limbaugh — and tuned in Amy Goodman and Democracy Now.

On hearing Reverend William Barber II speak about his revival of Dr. King’s 1960s Poor Peoples’ Campaign, Tucker knew he wanted to be part of it. He drove straight to DC, arriving for the 2018 launch of Barber’s National Call for Moral Revival.

“I realized then we all have a part to play in the political narrative of this country.”

Also at the launch was Sema Hernandez, a Texas Democrat making a quixotic bid for her state’s US Senate nomination. A community organizer, environmentalist, and pro-immigrant activist, Hernandez stood against child detention and for universal health care. Her views resonated with Tucker, whose home state still boasts the nation’s highest rate of medically uninsured. She suggested that Tucker join her at the June 28 Families Belong Together rally and candlelight vigil being organized by Mike Seifert of the ACLU-TX in Brownsville.

No sooner had he returned to Canyon Lake from DC, then he was off again. This time to attend in the same event that drew the newly-formed Angry Tías; the five friends who would soon become Team Brownsville; and Joshua Rubin and the Carbon Trace crew, who left their own vigil in McAllen to participate.

At the rally, Tucker met Ashley Casale and her then-7-year-old son, Gabe. They’d driven 2,054 miles from upstate New York as soon as school let out that summer to agitate for the reunification of families separated by Trump & Co’s “zero tolerance” policy. Denied access to every detention center they tried to tour, and every interview they tried to conduct, from Raymondville to Combes to Brownsville, they pitched a tent in front of Casa El Presidente. This “tender age shelter” — a euphemism for the hodgepodge of unregulated prisons holding babies and children up to 12 years of age all over the US — was managed by Southwest Key, the highest paid for-profit government-funded kids’ jailer in the US that year.

Tucker decided to join Ashley and Gabe. And when the 23-year-old redneck-turned-revolutionary steered his wreck of a car into the Casa El Presidente parking lot, it gave up the ghost. His fate with Brownsville was sealed.

Cooking for Team Brownsville

Gabe in front of the Casa El Presidente vigil encampment (photo by Ashley Casale, 2018); Brendon Tucker, Team Brownsville Chef (photo by Debbie Nathan, 2018)

Ashley eventually had to get Gabe back home for school. But Tucker remained, keeping vigil in front of Casa El Presidente for about two months. Brownsville residents grew curious as they passed by his tent and signs of “SILENCE IS BETRAYAL” and “WHAT IF IT WERE YOUR CHILD?” Some folks stopped, like Cindy and Mike Johnson, who brought Tucker home from time to time for a meal and a shower; and Sergio Cordova and Michael Benavides, of Team Brownsville, who urged their Facebook followers to bring Tucker water and sandwiches.

Mike and Sergio started crossing the Brownsville bridges that July with their colleagues and friends, Andrea Rudnik, Juan-David Liendo-Lucio, and Dr. Melba Salazar-Lucio. They brought food and water, tarps and diapers, medicines, flip flops, and clean underwear — whatever was needed — to the ever-growing scrum of asylum seekers halted on the wrong side of the border due to Trump & Co “metering” policy. The five were also helping to orient refugees newly released from detention, dumped by ICE without resources at the Brownsville bus station. But like Gabe, the five humanitarians would soon be heading back to school. They were all teachers.

What’s more, buying dinner for the asylum seekers was proving too costly — it was breaking their bank accounts. They needed someone to cook during the day. They asked Tucker if he’d like to join them as Team Brownsville’s chef. He signed right on, cooking all that fall and crossing with the others nearly every evening. He lived and worked from a small efficiency apartment the Team rented near the Gateway International Bridge, which he decorated with Poor Peoples’ Campaign posters.

“He was really enthusiastic. And full of energy. We created a GoFundMe to raise money for the rent and Tucker really took over. He cooked. We cooked. Volunteers came to cook. The New York Times did an article on us. It was the Tucker/Mike/Sergio show. They were the voices of our cause,” recounts Andrea Rudnik.

Tucker — with his booming voice, 6-ft stature, sandy hair, and light complexion — stands out in the borderlands, where skin tone and cultural influences are more Latin- than White-American. Nicknamed “ Whetto Loco” by some, and “Super Tucker” by others, he attracted the attention of other young activists who lured him away to start a similar kitchen in Tijuana. In December, he was off, saying he’d be back in a month. But Brownsville wouldn’t see him again until summer 2019.

“The Tijuana kitchen didn’t work out. There were, like, 6000 people in need there, not 100.”

There was also no existing structure, like Team Brownsville, to fall into, and his fellow activists were green and untested. The mission quickly fell apart.

On his way back to east, Tucker came face-to-face with another border injustice: the raping of sacred tribal lands to erect Trump’s physical wall. He stood with the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe of Texas — along with the two-person riverbank clean-up crew I’d just met — to stop construction…for a time. And he arrived back in Brownsville just in time to see Trump’s invisible wall — the Migrant “Protection” Protocol (MPP) — came crashing down.

From Cook to Camp Engineer

Brendon Tucker and Matamoros asylum seekers installing the first of 10 laundry sinks in the refugee camp, December 2019 (photo courtesy of Brendon Tucker)

Right about that time a 15-year-old refugee girl got sucked into the current while bathing in the fetid Rio Grande. Were it not for the refugees who jumped in to pull her out, and for the person who happened to be there that knew enough CPR to resuscitate her, she would have drowned.

She would not have been the first. She survived by pure dumb luck.

Gaby Zavala, also recently arrived in Matamoros and gunning to be of use, was enraged. Migrants were being fed by Team Brownsville; there were being sheltered by the Angry Tías. But they needed to get out of the river. They needed wash water.

Gaby called the local water plant and was told if she could supply the tanks, they would fill them. She set up a GoFundMe page, raising enough money to buy two. She sourced them in Brownsville, but needed to haul them to Mexico. She borrowed a truck, but — then heavily pregnant — needed someone to help her load it. She asked Tucker, and the two sweet-talked those tanks into Mexico and onto the levee.

They got to work that same day, building the rustic private showers I’d seen scattered throughout the camp on my first tour. And good thing they didn’t wait as Gaby gave birth the very the next day!

“People were so happy. They were singing in the showers,” Gaby recounts.

When GRM’s Project Manager, Blake Davis, suggested filtering the Rio Grande to bring potable water into the camp, Team Brownsville put up the money for two AquaBlocs. Tucker oversaw their installation and maintenance.

Then came the threat of COVID-19. And while the president tried to tweet away the reality of coming danger, prioritizing unlawful deportations of innocents over the health of his nation, Tucker took out his T-square and got to work. By the time the US sealed its border with Mexico in late March, he had designed and built 96 hand-washing stations throughout the Matamoros refugee camp. Then, he spearheaded an educational campaign to teach people how — and why — they should use them.

As this non-college-educated white male from the heart of Trump Country harnessed his ADHD to save lives, he discovered his calling as a water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) engineer in the process.

Brendon Tucker building a shelf for the camp pharmacy late one night in January 2020. (Tracy L. Barnett photo)

Love in the Time of Coronavirus & Climate Chaos

When the border closed, all the grassroots humanitarians in Matamoros, now operating as the Dignity Village Collaborative, had to decide in which country they would shelter. Tucker chose to stay in Mexico to help GRM build a field hospital for the care and isolation of potential COVID-19 patients. Just as they were putting the finishing touches on the 20-bed facility, disaster struck:

On May 16, a biblical storm ripped through the camp, turning the January dust into a May mudslide and destroying 200 of the 800 tents where 2,500 refugees had been living for eight, nine, even 10 months, waiting for their internationally recognized human right to an asylum hearing in the USA.

The border closure suspended court dates indefinitely, crushing hope. Now belongings were ruined by flood waters that coursed through the encampment like rivers. Having survived tragedies most of us can’t even imagine — from persecution by cartels to persecution by a US administration with a penchant for cruelty — the Matamoros refugees now face new hardships, like mosquitoes, mold, mildew, and more rain, for the official start of hurricane season was still two weeks away.

Team Brownsville and the Angry Tías sent in more tents as well as wheel barrows, shovels, pick axes, and pumps. Gaby negotiated with local Mexican officials to allow RCM to gravel the levee roads, pathways, and community areas. Mike and Cindy Johnson — Tucker’s first Brownsville benefactors — shared the cost of gravel with RCM. And Super Tucker got to work on his latest WaSH project: building a proper storm drainage system throughout the camp, aided by Erin Hughes. A Civil Engineer from Philadelphia, she’d presciently moved to Brownsville with her husband for a year to work in the Matamoros refugee camp. Tucker is so grateful to have her as a co-worker and guide.

Many Waters Cannot Quench Love, Neither Can Floods Drown it. — Song of Solomon 8:7

The Matamoros Refugee Camp, graveled by Tucker, Erin Hughes, and asylum seekers in preparation for 2020 hurricane season (photos by Brendon Tucker)

The Matamoros Refugee Camp, graveled by Tucker, Erin Hughes, and asylum seekers in preparation for 2020 hurricane season (photos by Brendon Tucker)

When last I checked in with Tucker, he was on the brink of exhaustion. Even his ADHD could no longer sustain him. He and Erin had been moving earth for days, expanding and reinforcing the irrigation canals I observed on my first walk through the camp.

They used topographical maps and common sense to locate the best spots in the levee terrain to create culverts to channel water away from the encampment and into the river. They’d already laid down 80-tons of gravel and were awaiting delivery of 80-tons more to secure the ground and create run off to mitigate another disaster.

“If INM had only allowed us to put up Better Shelters,” Tucker reminisced, “I’d be bringing in electricity right now instead of digging ditches.”

It turns out the Dignity Village Collaborative had pitched this idea to local Mexican officials back in the fall, 2019. That’s why there were three in the camp, donated to GRM.

“What keeps you going?”

“It’s nice to be part of something bigger than myself. Working with Gaby and GRM, with the Tías and Team Brownsville — all the members of the Dignity Village Collaborative — nothing gets done alone. Everything we do is in tandem. Best decision I ever made was to come, then come back, to Brownsville.”

“Brendon Tucker is a remarkable young man, extremely bright, but more important he’s a decent, generous human being.” — Joyce Hamilton, Angry Tías

“Tucker is a young man with a heart of gold. I’m honored that he calls me dad.”

— Sergio Cordova, Team Brownsville

“I’m proud to have Brendon Tucker as a friend. He’s a damn good kid with a genuine desire to make people’s lives better.” — Cindy Candia, Angry Tías

So you see, even a conservative libertarian from Texas Hill Country can turn toward the light. All it takes is a commitment to boycott Rush Limbaugh and Fox News and a refusal to look away.

Sarah Towle is an award-winning London-based US expatriate author sharing her journey from outrage to activism one story of humanity and heroism at a time. Her story on the Angry Tías and Abuelas ran here in April. This is Episode 11 in her travelogue of a road trip gone awry: THE FIRST SOLUTION: Tales of Humanity and Heroism from Trump’s Manufactured Border Crisis, rolling out on Medium as fast as she can write it — because, in Sarah’s words, “it’s Just. That. Urgent.”