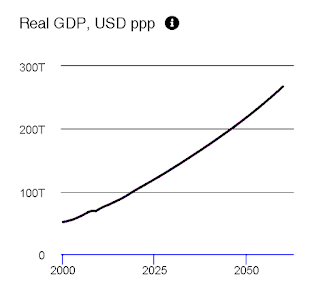

It is not unusual to hear someone make definitive statements about the distant future as if they were facts. How often have we heard something like the following: The world economy will double in size by 2050.

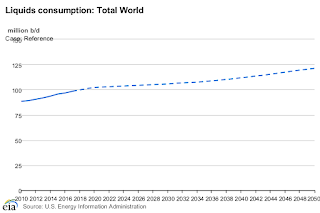

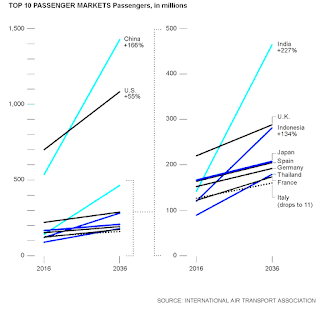

When people represent such “facts” in chart form, those facts become somehow more convincing. (You need to click on the charts below to see them clearly):

|

| SOURCE: OECD |

But, of course, these charts in no way represent reality, not least because much of the time period covered by them has not happened. Philosophically, the problem represented by those charts is the problem of induction. We assume at our peril that when a pattern is repeated long enough that that constitutes “evidence” the pattern will continue for a long time into the future. Of course, the reason for representing at least some of the past in these charts is to cement just that view.

So, how might we think of the supposed unprecedented declines in oil consumption, air travel and economic activity in general in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic? No one yet knows their true extent worldwide, but the decline in oil consumption has been estimated at 25 million barrels per day or 25 percent of world oil production. GDP estimates for contraction of the world economy are wildly uncertain but dire. One economic forecasting firm predicts that for the current quarter in the United States the annualized rate of contraction will be 37 percent. The most dramatic figure I could find is that the number of airline passengers was down 96 percent in the United States in early April.

Most experts would dismiss these numbers as one-time aberrations that could be safely ignored in the long run. But it is precisely the size of these “aberrations” that makes them hard to ignore. Nevertheless, there is a general view that the coronavirus is an outlier, and when we get a vaccine, the economic and other effects associated with the virus will go away.

Of course, there are several problems with the last sentence. First, the coronavirus may not be an outlier. We humans are now routinely pushing into habitats where all sorts of viruses lurk, viruses which might become the cause of the next pandemic. When we push into these areas, we call it development. Viruses (if they could speak) would call it an opportunity.

Second, vaccines are not always easy to develop and even when they are successful, the viruses at which they are targeted may mutate in ways that make the vaccines useless.

Third, the idea that the problems that have beset us are due to the coronavirus alone is far too simplistic. This assumes that the pandemic came into a social and economic system that was without major fragilities, one that will return to its previous state when the pandemic is over.

Of course, events have now illustrated that global society is not going to return to its state prior to the pandemic. National governments are spending freely and going deeper and deeper into debt. Even so, state, provincial and municipal governments (which aren’t allowed to print money) will have to cut back services and employees drastically. A wide array of businesses are going and will continue to go bankrupt. That retail districts throughout the world will have many empty stores formerly occupied by retailers large and small seems inevitable. That airline travel will not reach the heights anticipated by the charts above seems highly likely.

There is no way to know how long the wrenching changes we are experiencing will go on or how our arrangements for commerce, governance and social life will change. What is missing and has been missing is a map our fragilities. The pandemic revealed those fragilities for all to see; but they were not invisible. A belief in the invincibility of our global systems obscured them.

How might we start to map out more clearly what is fragile and what is not and choose better arrangements that will make us less fragile (and possibly prosper) in the face of future disruptions? First, we can identify some characteristics of fragile systems:

- Centralized

- Tightly networked

- Optimized for “efficiency”

- Lacking redundancy

This is not a complete list, but it is a good start. The implications of these characteristics are now on display practically everywhere in the world. We centralized much of the production of hospital supplies in one country, China.

We created a tightly networked logistics systems based largely on just-in-time delivery methods (meaning minimal inventories), a system that can be crippled by the failure to deliver one component of a product. We optimized our health system for “efficiency” and so lack surge capacity. Surge capacity costs money to maintain and is thus labeled “inefficient.” Perhaps the most visible manifestations are the lack of masks and protective equipment for hospital workers.

The pattern just outlined is now almost everywhere embedded into our systems of commerce.

Of course, the challenge is not merely to identify fragility but to suggest an alternative. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of Antifragile, provides a book-length guide. I’ll quote his definition of antifragile:

Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile.

My attempt to summarize these ideas can be found here. Some general characteristics will seem like a mirror image of the list above:

- Decentralized

- Loosely networked

- Optimized for survival/transformation in the face of shocks

- Built-in redundancy

Understanding the concept of antifragile really requires of careful reading of Taleb’s book. I recommend that book as a companion to our efforts to remake the fragile systems which are crumbling around us.

Image: “Balanced Herself Uprightly on that Precarious Footing” Illustration from a 1908 publication of “Anne of Green Gables” by L.M. Montgomery Wikimedia Commons