Across the world, Covid-19 has triggered community action on a vast scale. It’s a powerful riposte to both government and private money.

You can watch neoliberalism collapsing in real time. Governments whose mission was to shrink the state, to cut taxes and borrowing and dismantle public services, are discovering that the market forces they fetishised cannot defend us from this crisis. The theory has been tested, and almost everywhere abandoned. It may not be true that there were no atheists in the trenches, but there are no neoliberals in a pandemic.

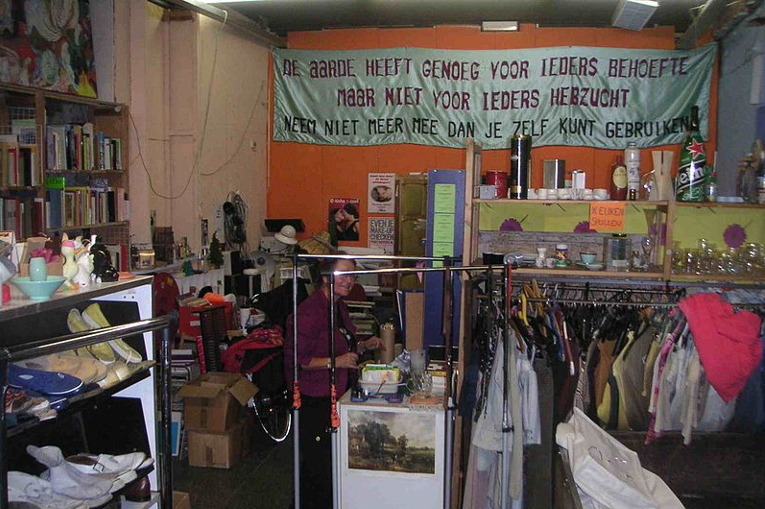

The shift is even more interesting than it first appears. Power has migrated not just from private money to the state, but from both market and state to another place altogether: the commons. All over the world, communities have mobilised where governments have failed.

In India, young people have self-organised on a massive scale to provide aid packages for “daily wagers”: people without savings or stores, who rely entirely on cash flow that has now been cut off. In Wuhan, in China, as soon as public transport was suspended, volunteer drivers created a community fleet, transporting medical workers between their homes and hospitals.

In South Africa, communities in Johannesburg have made survival packs for people in informal settlements: hand sanitiser, toilet paper, bottled water and food. In Cape Town, a local group has GIS mapped all the district’s households, surveyed the occupants, and assembled local people with medical expertise, ready to step in if the hospitals are overwhelmed. Another community in the city has built washstands in the train station and is working to turn a pottery studio into a factory making sanitiser.

In the US, HospitalHero connects healthcare workers who don’t have time to meet their own needs with people who can offer meals and accommodation. A group called WePals, created by an eight-year-old, sets up virtual play dates for children. A new website, schoolclosures.org, finds teaching, meals and emergency childcare for overstretched parents. A network called Money During Corona texts news of job opportunities to people looking for work.

In Norway, a group of people who have recovered from Covid-19 provide services that would be dangerous for non-immune people to offer. In Belgrade volunteers organise virtual coffee mornings and crisis counselling. Students in Prague are babysitting the children of doctors and nurses. Estates in Dublin have invented balcony bingo: the caller sits in the square between the blocks of flats with a large speaker, while the players sit on their balconies, taking down the numbers.

In the UK, thousands of mutual aid groups have been picking up shopping and prescriptions, installing digital equipment for elderly people and setting up telephone friendship teams. A mothers’ running group in Bristol have restyled themselves “drug runners”, keeping fit by delivering medicines from chemists’ shops to people who can’t leave their homes. A virtual pub quiz organised on Facebook brought together more than 100,000 people.

Rooftop aerobics, singing and letters: how communities are coping in coronavirus quarantine – video

Around the world, self-organised groups of doctors, technicians, engineers and hackers are crowdsourcing missing equipment and expertise. In Latvia, programmers organised a 48-hour hackathon to design the lightest face shield components that could be produced with a 3D printer. A number of UK groups are encouraging companies with protective equipment in their storerooms to give it to frontline health workers. In the Philippines, fashion designers have repurposed their workshops to produce protective suits. Sharing techniques through the website PatternReview, home sewers have been mass-producing masks and scrubs.

In just one week, a group of doctors, technicians and other experts organised themselves to design a crowdsourced ventilator, the OxVent, which can be produced from widely available parts for under £1,000. Another design, VentilatorPAL, can be manufactured for $370, according to the community of technicians that created it. The Coronavirus Tech Handbook is an open-source library pooling technologies and new organisational models for beating the pandemic. In the US, self-organised expert groups are filling some of the catastrophic gaps in public health provision, carrying out testing and tracking projects, creating directories of vulnerable people and speed-matching medical specialists with the hospitals that need them.

The horror films got it wrong. Instead of turning us into flesh-eating zombies, the pandemic has turned millions of people into good neighbours.

In their book Free, Fair and Alive, David Bollier and Silke Helfrich define the commons as “a social form that enables people to enjoy freedom without repressing others, enact fairness without bureaucratic control … and assert sovereignty without nationalism”. The commons are neither capitalist nor communist, market nor state. They are an insurgency of social power, in which we come together as equals to confront our shared predicaments.

A thousand books and films and business fables assure us that the fairytale ending to which we should all aspire is to become a millionaire. Then we can isolate ourselves from society in a mansion with high walls, with private healthcare, private education and a private jet. The commons envisages the opposite outcome: finding meaning, purpose and satisfaction by working together to enhance the lives of all. In times of crisis, we rediscover our social nature.

You can tell a lot about a society from its quirks of language. We repeatedly misuse the word “social”. We talk about social distancing when we mean physical distancing. We talk about social security and the social safety net when we mean economic security and the economic safety net. While economic security comes (or should come) from government, social security arises from community. One of the extraordinary features of the response to Covid-19 is that, during this self-isolation, some people – especially elderly people – feel less isolated than they have done for years, as their neighbours ensure they are not alone.

We still need the state: to provide healthcare, education and an economic safety net, to distribute wealth between communities, to prevent any private interest from becoming too powerful, and to defend us from threats. It currently performs these functions poorly, by design. But if we rely on the state alone, we find ourselves sorted into silos of provisioning and highly vulnerable to cuts. Rich social lives are replaced with cold, transactional relations. Community, then, is not a substitute for the state, but an essential complement.

There is no guarantee that this resurgence of collective action will survive the pandemic. We could revert to the isolation and passivity that both capitalism and statism have encouraged. But I don’t think we will. I have the sense that something is taking root now, something we have been missing: the unexpectedly thrilling and transformative force of mutual aid.