This article was written for and originally appeared on the website World Water Reserve. I strongly recommend checking it out. The posts deal with both the global picture and the practical local applications of water use.

Water is invisible to most people in developed countries. We turn on the tap, and there it is. It’s provided free in restaurants, without our even asking for it. We can spend money to buy water in bottles, but in America at least, we’re never far from a water fountain. There have been revelations recently of lead or other contaminants in water supplies, but still the concept of a universal “water supply” is rarely questioned.

Infrastructure . . .

This easy access to water is not the case in many places on earth and was almost never the case in the past. And it’s looking like it will not be the case in the future, as sea level rise threatens fresh water supplies, energy resources are depleted, political systems lack the will or ability to maintain infrastructure, and climate change creates unpredictable rainfall and temperature patterns around the globe.

Welcome to low-water living

If our water systems collapse, or if we decide to simplify voluntarily, individuals and households may be surprised at the lifestyle changes that will be necessary. What we own, how we use it, and even our domestic architecture will be affected. This was something I had to learn during two years without running water in Liberia and seven years with erratic running water in Kyrgyzstan. I offer my experiences in living without reliable water sources not because I’m the expert. There are millions of people around the world who have managed their whole lives on a tiny fraction of the water we consider necessary. But perhaps I can describe to you what living with unpredictable water is like and make it less daunting.

One of the first things I noticed when I walked into a market in Liberia was the number of objects designed to carry water. The road leading up to the bazaar in our town was lined with dozens of booths stacked high with enameled metal and plastic dishpans, laundry tubs, buckets, children’s potties, scoops, barrels, bowls, cups, bottles, and more. My first reaction was surprise at the number and variety – who would need all those things? I never did in the US – but within the first week of setting up household, I had to visit these booths many times.

Because this is what a typical house without plumbing is like. Kitchen amenities consist of flat tables with no built-in sink, drains, or taps. The toilet is an outhouse. The bathing room might be an outside enclosure with a gravel surface or a room indoors; if it’s indoors, it’s just an empty space with a cement floor and a sluice hole at the foot of the wall. Laundry is done in a tub outside, with a washboard if one is lucky. There are no fixtures built into the house for brushing teeth, washing hands, doing dishes, or filling a drinking cup. So every householder has to design systems herself to manage water.

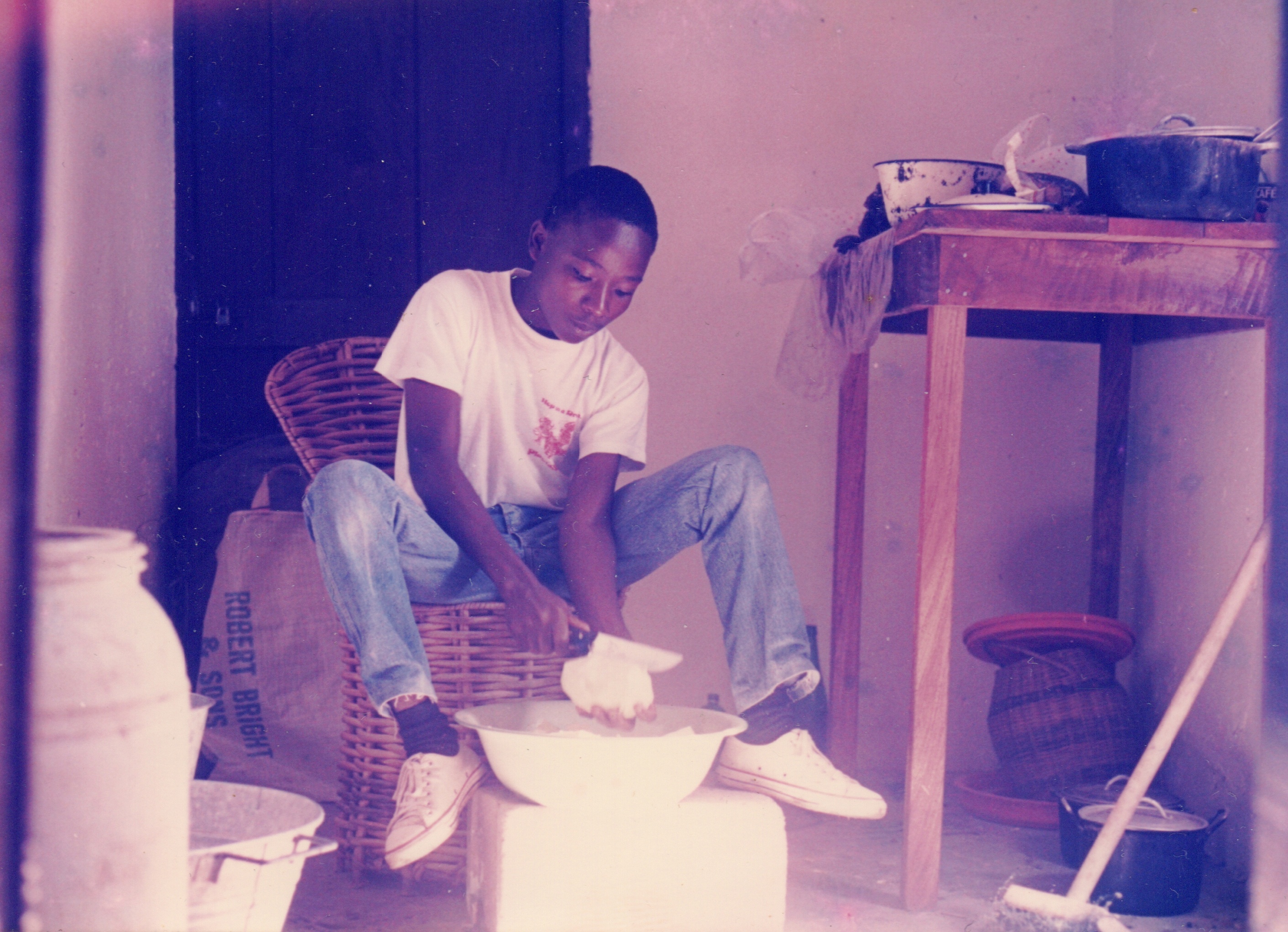

Liberian kitchen

The house where my husband and I lived in Liberia wasn’t as primitive as most, but that was not an unmixed blessing. We were in a regional capital, and our house was connected to a notional town-wide water system that no longer worked. So we had an indoor tub and toilet and a rickety kitchen sink, but we didn’t have any water entering the pipes.

Once I had bought dishpans to set in the useless sink, a 30-gallon storage barrel, several buckets for bathing and housecleaning, two big tubs for washing and rinsing laundry, and many smaller storage vessels, the issue became getting the water to put in them. Every five or six days, my husband loaded the barrel and a bucket onto the wheelbarrow and walked ten minutes downhill to the “swamp,” as it was called, an open area where reasonably clear water bubbled up and collected. Then he had to push the heavy barrel back up the hill to get it home. He’d set it in the kitchen next to the dishpans, and I’d hang a plastic scoop over the handle. We’d boil drinking water and store it in glass jars, in our case old Tang juice powder jars, a luxury that our neighbors couldn’t afford to accumulate. When we needed to bathe, we’d fill a bucket up halfway, stand in the tub, and use a scoop to wet ourselves, soap up, and rinse. We did laundry once a week and kept the items that had to be washed to a minimum. Our old dishwater and laundry water was used to flush and clean the toilet as well as to wash floors. During the rainy season we collected runoff from the roof, which was usually too dusty for drinking or laundry but could be used for flushing and cleaning.

He has a system.

This would probably seem unpleasant and difficult to those not used to it, but it really wasn’t. The biggest difficulty was getting through the silent-movie-slapstick phase of not having a system or the proper vessels for everything that needed to be done – standing naked in the bathroom with a bucket and no scoop, wondering how this is supposed to work, then scampering through the house to find something to use; unthinkingly dunking dirty hands into a full container and realizing all the things that now can’t be done with that water; wandering around the house with a dishpan of rinsewater, checking to be sure that there is nothing else to be done with it before it gets thrown out; even realizing you forgot to boil enough water for the next day and wondering whether diarrhea is really that easy to catch (it is). But soon enough we’d figured out the process and didn’t even think about it anymore.

There were some things I noticed about my water use in Liberia. My toes were never clean, except for a few times a year when I had to travel to the capital city and had enough water to soak in a bath. I was never frivolous about tossing clothes in the washing pile until they really needed it, and I had many fewer clothes. I drank all of everything I had to drink, right away.

Sharing water

And there were some things I noticed about how water affected the Liberian lifestyle. Hospitality in Liberia is water. You must give people something to drink. Strangers will knock on the door asking for a glass of water. We would sometimes get frustrated, because people would ask always for “cold water,” and if we got electricity to run the fridge for more than a few hours a week, we were lucky. But then we found out that “cold water” is also a euphemism for a bribe; a checkpoint soldier would mutter, “You must find me cold water” while refusing to raise the roadblock. Water is an item of utmost value, never taken for granted.

Years later, after we had children, we moved to Kyrgyzstan in the mountains of Central Asia, a climate and culture as different from Liberia as it could be. The climate was high, cold, and dry, and the culture was reserved and nostalgic for lost Soviet conveniences; Liberia’s climate was low, hot, and wet, and its culture was exuberant and entrepreneurial. But although the causes for water challenges and the solutions that the Kyrgyz came up with were sometimes different, we faced many of the same issues in daily life.

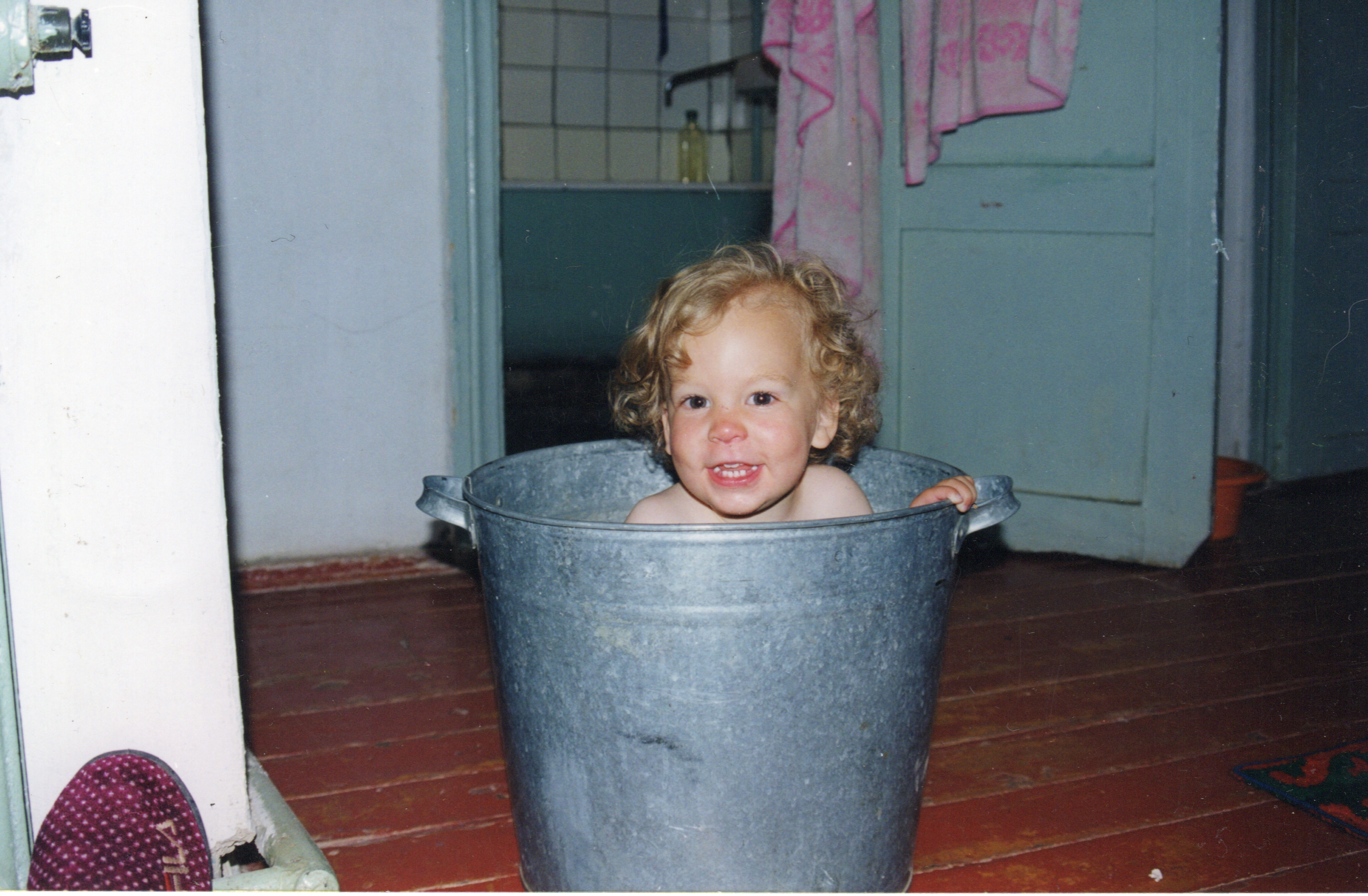

The baby and the bathwater

Our house in Kyrgyzstan had running water – most of the time. There was an indoor toilet, a bathtub, and a sink in the bathroom. When the water worked, it was almost always bitterly cold. (I found that potty training went pretty quickly with my two youngest children; they had powerful motivation not to have an accident and get cleaned up with water barely above freezing.)

The bathroom was big enough to set a small, open-topped electric washing machine in the corner. This had to be filled, heated, and drained by hand and could hold two pairs of jeans or one bed sheet or a few shirts in a single load. All laundry was then hung on the line outside, which meant that half of the year it freeze-dried. Once my daughter came inside from playing in the snow, sobbing and holding her head. “What’s wrong?” I asked her. “I hit my head on a sheet!” she wailed. That incident summed up life in Kyrgyzstan for me.

There was no room designated as a kitchen when we first moved in, so once we chose one, we had to carry water into and out of it. We eventually had a friend come and install a sink and cold water in the kitchen, which was a wonderful luxury. We heated all water in a metal bucket with an immersible heating coil, perhaps one of the most dangerous objects I’ve ever been around but a necessary part of life. On the table next to the kitchen sink stood our big bucket filter for drinking water. It did a great job, but of course our children drank from other sources around town when I wasn’t monitoring them and came down with occasional water-borne illnesses.

That describes what it was like when the water worked. There were times when it would quit working more or less randomly and two times of year when it would certainly be unreliable. The first was in the depths of winter, when for all of January the temperature would never rise as high as zero degrees Fahrenheit (minus 18 Celsius); at that time both incoming and outgoing pipes were likely to freeze. We had an outhouse in our yard, which we were grateful for, but it wasn’t fun to trot outside at all times of the day and occasionally night when it was so cold our eyelashes froze the second we opened the door. Small children with many layers of clothing were especially resistant, so we did have a chamber pot for them.

Kyrgyz tap water in spring

The other time when water usually wouldn’t work was late spring. The headwaters of the river that becomes the Syr Darya ran through our town and were fed by melting glaciers in the mountains around us. For several weeks in the spring the water that came through our pipes was a soup of silt and sand. Sometimes the pipes would get blocked entirely for a while; even when they worked, all the water had to be allowed to settle in buckets and then the clearer water carefully skimmed off the top before it could be used for cleaning or washing or be run through the water filter.

Frozen pump

When we had no water in the house, someone – usually our most sociable and bilingual child – had to take a bucket to the neighborhood pump. This was a collection spot for gossip and play. In the winter, the inevitable leaks froze into a volcano shape with the tip of the pump sticking out the peak. This made the task of filling a bucket challenging, since one had to operate the pump and hold the bucket all while sliding downhill and away. The kids loved it, thankfully, so fetching water was generally their job – although the buckets were not terribly full when they got them home.

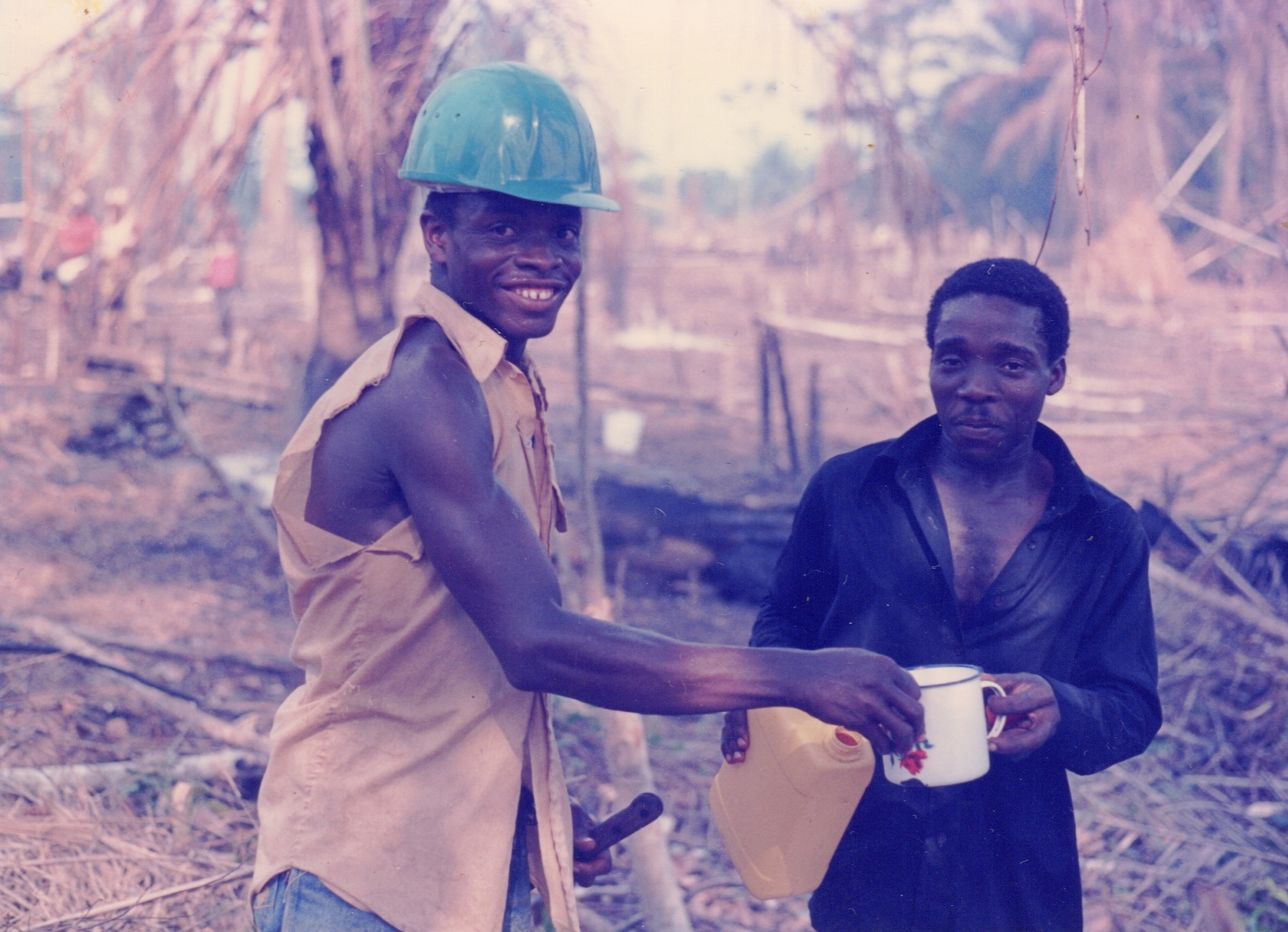

Hauling water in the village

These processes in Liberia and Kyrgyzstan take a long time to describe, but they quickly became second nature to us. Life there was not suffering, although there were some risks we faced and many luxuries we did without. We were more fortunate than some of the people we lived with, of course. We had a water filter, we could afford to plumb a sink in another room, we had glass jars to store water in – many didn’t. In more remote Kyrgyz villages, water had to be hauled from farther and made to last longer. I was impressed with how little water women could use to wash dishes, for example, but then I also was struck with how much more common tuberculosis was there. There were other diseases that could have been lessened or prevented by a greater ability to wash oneself and one’s belongings, but that was due to education and culture as much as to availability of water.

Desertification in Africa

The water situation was even more challenging in other countries. Uzbekistan is Kyrgyzstan’s neighbor and relies on the Syr Darya for its water and Kyrgyz hydroelectric plants for its electricity. Many towns in Uzbekistan have almost no access to water and buy their supply weekly from tanker trucks that come through town. In the not too distant future, even that supply may dry up. As the climate warms, the glaciers in the Tien Shan and other Central and South Asian mountain ranges are shrinking. All of Central Asia and much of other areas of Asia rely on the rivers fed by those glaciers for every aspect of life – but the glaciers will soon become unreliable and eventually vanish. Thriving cities like Bishkek, Tashkent, Samarkand, Osh, and Bukhara may become unable to support their current populations. We can expect then to see the same mass migrations we saw in the American West during the Dust Bowl in the 1930s and in Syria during the last few years. The severe droughts and desertification going on around the globe are a more serious problem than just adapting to using less water; some people will simply have none, and the only adaptation open to them will be moving. That is a larger issue than I can address in this essay, but it is a critical one.

So what should residents in developed countries do about worldwide water issues? I’m not saying you should disconnect your plumbing and live like the Liberians or Kyrgyz I knew. I always hated the “There are people starving in [insert fashionable famine-stricken land here], so eat your food” approach when I was young. It won’t do Uzbeks or Syrians any good at all if you turn off the tap when you brush your teeth. Using less water will reduce energy costs of purification and pumping and may protect your local aquifer or cut down on water imports, depending on where you are; these are important things, but they really aren’t going to make much practical difference worldwide.

I think, however, that there is an important psychological element as we face a future of climate change, energy shortages, and consequent political instability: we need to feel ourselves competent to meet challenges. We shouldn’t be like those people who say, “Oh, I could never live without my indoor plumbing.” Of course we can. I did, and you can, too; you could live with less water right now. It will be good training for us. We need to accept upcoming changes not just with competence but with a sense of cheerfulness, fun, and adventure. Living with limited water really isn’t that bad, and spending more hours every day on tasks of basic survival rather than on video games or other maladaptive time-killers will actually make us happier in the long run. So think about your water use, enjoy it while you have it, use it wisely, and face future challenges with the knowledge that you can manage and even thrive.

Making the most of water

All photographs by Andy Zehner