This is the second in a weekly series of essays by Dougald Hine, our new Commissioning Editor at Bella Caledonia. Notes From Underground is also available as a podcast and on YouTube.

I was passing through Brussels on my way to London last October. A message had come through Facebook from someone I’d never met, and we found each other in a café near the Eurostar terminal at Gare du Midi.

Working for an organisation close to the European institutions, my new contact had just completed a report on the future of shipping.

‘To make the numbers work, I had to assume that, by 2030, half of Europe’s entire electricity supply will be used to produce the synthetic fuels to keep the container ships coming from China.’

In offices across the city, reports were being written that made similar assumptions for other industries. Think of the total projected electricity supply as a budget: this budget was being spent many times over in order to explain how goals for decarbonising the European economy could be met without questioning the assumption of continued economic growth. In order, that is, to allow the report writers’ bosses to go on avoiding that question.

We sat there with our cappuccinos, pondering this state of affairs. How do you break the silence, we asked each other, without becoming someone no-one listens to?

* * *

I heard a story about what happened when Greta Thunberg met Macron.

By now, it was February. For three months the French president had been under siege as yellow vest protesters made their anger felt on the streets and at the roundabouts. The trigger for this movement, the move that pushed people to breaking point, was a clumsy attempt to drive the transition to a green economy by pushing up the price of fuel at the pump. It is tempting to imagine that Greta’s visit to the Elysée came as a relief, relatively speaking, though the frankness of the conversation that followed is still surprising.

‘France is unable to decrease its emissions,’ Macron told her, ‘because of its economic growth.’

In a recent issue of the journal New Political Economy, Jason Hickel and Giorgos Kallis ask ‘Is Green Growth Possible?’ They set about examining the empirical basis for claims about the decoupling of economic growth from environmental impact. Their findings are damning. The drop-off in advanced economies’ resource use – heralded by proponents of green growth as the moment when we passed ‘peak stuff’ – turns out to be a statistical illusion created by the offshoring of manufacturing. Once you take into account the resources used in factories elsewhere to produce the goods and services we consume, the growth of our economies is more stuff-dependent than ever. Meanwhile, the ever-narrowing pathways towards the Paris goals for limiting global warming are paved by carbon capture technologies that are either ‘unproven or dangerous at scale’ – or dependent on decarbonisation rates, if we start right now, that are vastly greater than seems plausible for any economy without an overall slowdown in activity.

Having surveyed the evidence and probed the models, Hickel and Kallis conclude that green growth is a fantasy born out of desperation. ‘It is not politically acceptable to question economic growth,’ they write, ‘therefore green growth must be true, since the alternative is disaster.’

That’s what is so interesting about the conversation between Greta and Macron. We are no longer in the territory of anonymous underlings wondering how to broach the unspeakable with their bosses. Once the incompatibility of economic growth and ecological viability has become speakable in a room like the one where that meeting took place, we are crossing an event horizon. I’m not sure anyone knows how things work on the far side.

* * *

This spring I was back in Brussels, alongside Alison Green of Extinction Rebellion and Jem Bendell, the author of the Deep Adaptation paper, at an event hosted by the European Commission.

My message that day was that sustainability is over: the challenge now is not to make the current European way of living sustainable, but to negotiate the surrender of this way of living. That means the decommissioning of whole areas of current economic activity, but also the decommissioning of deeply held beliefs and assumptions, including the growth assumption.

Among the buzz of emails that followed that event, one stuck in my mind. It came from an economist who works at the Commission, and it concerned what he referred to as ‘the unresolved question of delinking’.

The crux of this, he suggested, is not to do with the measurement of GDP, but the viability of the European social model. If we accept that the long-term trend of economic growth cannot continue, this is not just a problem for Amazon and Tesco, it’s a problem for the National Health Service, the schooling system and the welfare state. This is one of those places where the right are right, while many of us on the left prefer to avert our gaze: the best achievements of the model we inherited from the twentieth century, which was built in the aftermath of two world wars and one depression, and which we sought to defend through four decades of neoliberalism, are dependent on the functioning of a capitalist economy that cannot operate in the absence of growth.

‘I have not seen any proposal so far that even comes close to addressing the issue,’ his email went on. ‘Most of the talk is about investment, a climate bank, etc., but the much bigger problem is the addiction to current rates of growth via the public spending programmes.’

This is the conversation about decoupling that we need to have.

* * *

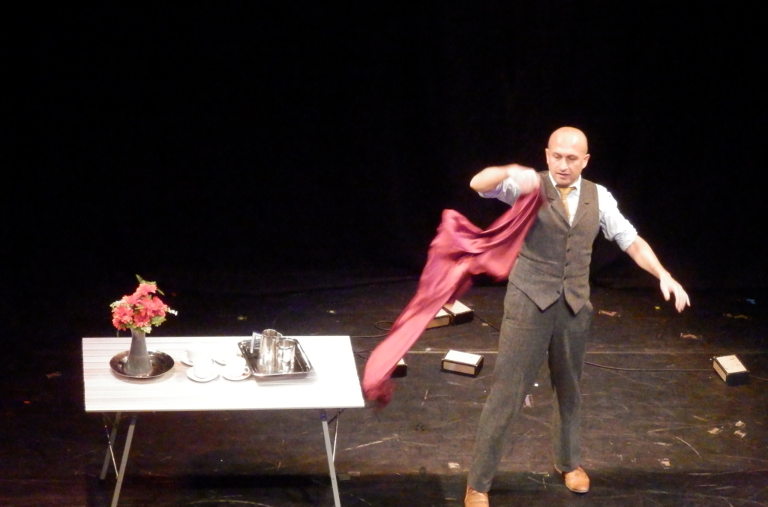

The need for economic growth is a social construct, not a law of nature, but this construct is the tablecloth on which our current society has been arranged. The question we face, as the 2020s come around, is whether we can pull the tablecloth out fast enough without smashing all the plates and glasses?

What clues do we have as to how to do this? They may not be legible to people who sit in offices in Brussels, or to the bosses they need to convince. They won’t look much like policy proposals, our pathways out of this, depending as they likely will on human capacities that lie beyond the logic of the state or the market. Yet it will be necessary to build bridges and to keep lines of communication open with those within existing institutions who grasp the situation.

People have been working on ‘degrowth’ economics for decades. Giorgos Kallis, the co-author of the ‘green growth’ paper, is one of them. When the incompatibility of growth and life has become speakable in the Elysée Palace, it is time for these people to move to the centre of the conversation. At a moment like this, the words of Milton and Rose Friedman come to mind:

We do not influence the course of events by persuading people that we are right when we make what they regard as radical proposals. Rather, we exert influence by keeping options available when something has to be done at a time of crisis.

To find our bearings in a landscape beyond growth, my own suggestion would be to revisit the thinking of Ivan Illich. Writing in the 1970s, he called into question the achievements of the post-war social model, illuminating the counterproductivity and hidden destruction built into our systems for schooling, healthcare and economic development. When our dependence on such systems is what makes it so hard to question the growth assumption, the work of Illich and his friends brings other options into view. In particular the work of those such as Gustavo Esteva and John McKnight, who brought Illich’s thinking into dialogue with the experience of communities at the grassroots, in the barrios of Mexico City and the housing projects of Chicago. Their practical experience mobilising human potential that lies beyond the reach of the market and the state is the fruit of decades of collaboration. Bring it together with the work of the feminist economists J.K. Gibson-Graham, and with David Fleming’s Lean Logic, and we start to find clues as to what still works when we abandon the pretence that green growth can save us.

Teaser photo credit: Isabelle Adam