Rich nations’ proposals for greening the economy need to acknowledge that their wealth rests on economic exploitation and ecological spoliation of poorer countries.

The Green New Deal (GND), Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s draft legislation to reduce US carbon dioxide emissions, was literally 2019’s talk of the town.

Climate apocalypse is on everyone’s mind. The spring of 2019 was the season of failed monsoons in Chennai, its reservoirs meters from desiccation. Millennial heatwaves roiled France. Wildfires raged in the United States, and continental firestorms rake Australia. The normally cool prose of scientists has been heating up as well, channeling the anxiety induced by the catastrophic conditions they describe. Reports warning of the disappearance of the world’s flora, fauna, and land increasingly seem like forecasts for the end of the world. Climate change has and will continue to pulverize the global South, where disaster is not on the horizon but has already arrived. Yet at the moment, the most visible environmental legislation — the Green New Deal (GND) — is being made and unmade in the North, the primary polluter and home of the largest corporations.

Industrial upgrading requires metals and metal-mining displacement of the people living on that land and pollution. Toxic levels of cobalt, which is used in electronics, have been found in the blood and urine of the miners in the Democratic Republic of Congo, especially children. Photo courtesy of Fairphone.

Like the New Deal to which the GND refers, it aims big. In the words of Demond Drummer, the head of the New Consensus think tank, the quiet catalyst of the GND discussion, it is a domestic agenda for governing, a chance “to see the elephant whole.”

Saikat Chakrabarti, Ocasio-Cortez’s former Chief of Staff, has added that “we really think of it as a how-do-you-change-the-entire-economy thing.” Meanwhile, Ocasio-Cortez has spoken warmly of Tennessee Valley Authority-style programs and “public-private partnerships.” She has put forward the figure of ten trillion dollars as its cost.

Ocasio-Cortez’s draft legislation, much like the draft document from the New Consensus, was bare bones. Its five goals are:

(1) To achieve net-zero emissions through a “just transition;”

(2) Create millions of high-wage and good jobs;

(3) To “invest in the infrastructure and industry of the United States”;

(4) To ensure clean water and air, as well as climate and community resilience; and

(5) Repairing, stopping, and heading off “historic oppression of the “frontline and vulnerable communities,” whether identified as marginalized by poverty or origin.

The proposal does not map specific projects, only general areas of “invest[ment] in the next generation of American industry and innovation.”

The call for meeting 100 percent of power demand through “clean, renewable and zero-emission energy sources” deserves praise. But direct investment “into feeder industries including clean steel, aluminum, and other related industries” raises more questions than answers: Why does the plan to “green” the industrial sector involve mostly swapping in “clean” processes for dirty ones while accepting the existing level/quantity of industrialization as acceptable, and also accepting the existing hierarchies linked with industrialization. Similarly, promoting the “international exchange of technology, expertise, products, funding, and services… a new green economy, producing solar panels and solar farms, windmills, hydroelectric plants, carbon-neutral automobiles…and a host of other products,” sounds more like anti-racist Green Keynesianism than any kind of eco-socialism.

The Bernie Sanders legislation has been far stronger, with more – but still not enough – emphasis on climate debt, a very strong agricultural plank, which is good.

But it also has a huge section devoted to electrifying the car industry, which is a giveaway to a big US industrial sector. (The focus, instead, should have been boosting on public transportation.) Indeed, while in other ways the Sanders GND has broken from the green capitalist consensus, in regards to its emphasis on greening industry, it shares common ground with ideas promoted by other programs like the New Consensus and the Australian Breakthrough (The National Centre for Climate Restoration).

It should not come as a surprise that proposals from the heart of wealthy, industrialized, and capitalist countries like the US or Australia focus on new hi-tech. And we do need some of this tech. But how much? At what cost? And who will pay it? Who will profit from it? How long will it take to come online? Who will benefit from it? The devil is in the details.

In essence, the GND proposals are development programs. But what is development? Opinions differ. Mainstream theories of development argue that the poor can “catch up” to the wealthy and that development and underdevelopment are different stages of the same process. Other theories of economic and ecological change teach us that underdevelopment and development are Siamese twins — the wealth of the rich rests on the poverty of the wretched. Because the number of countries which have “caught up” can be counted on one hand, history tells us that the latter theories are largely the correct ones.

As the GND’s crafters admit, their proposals are really policies for managing the world’s economic system. None of these proposals properly acknowledge that the wealth of the richer countries rests on economic exploitation and ecological spoliation of the poorer ones. Each contains the coding to make “normal” an entire world of development and underdevelopment, wealth and want.

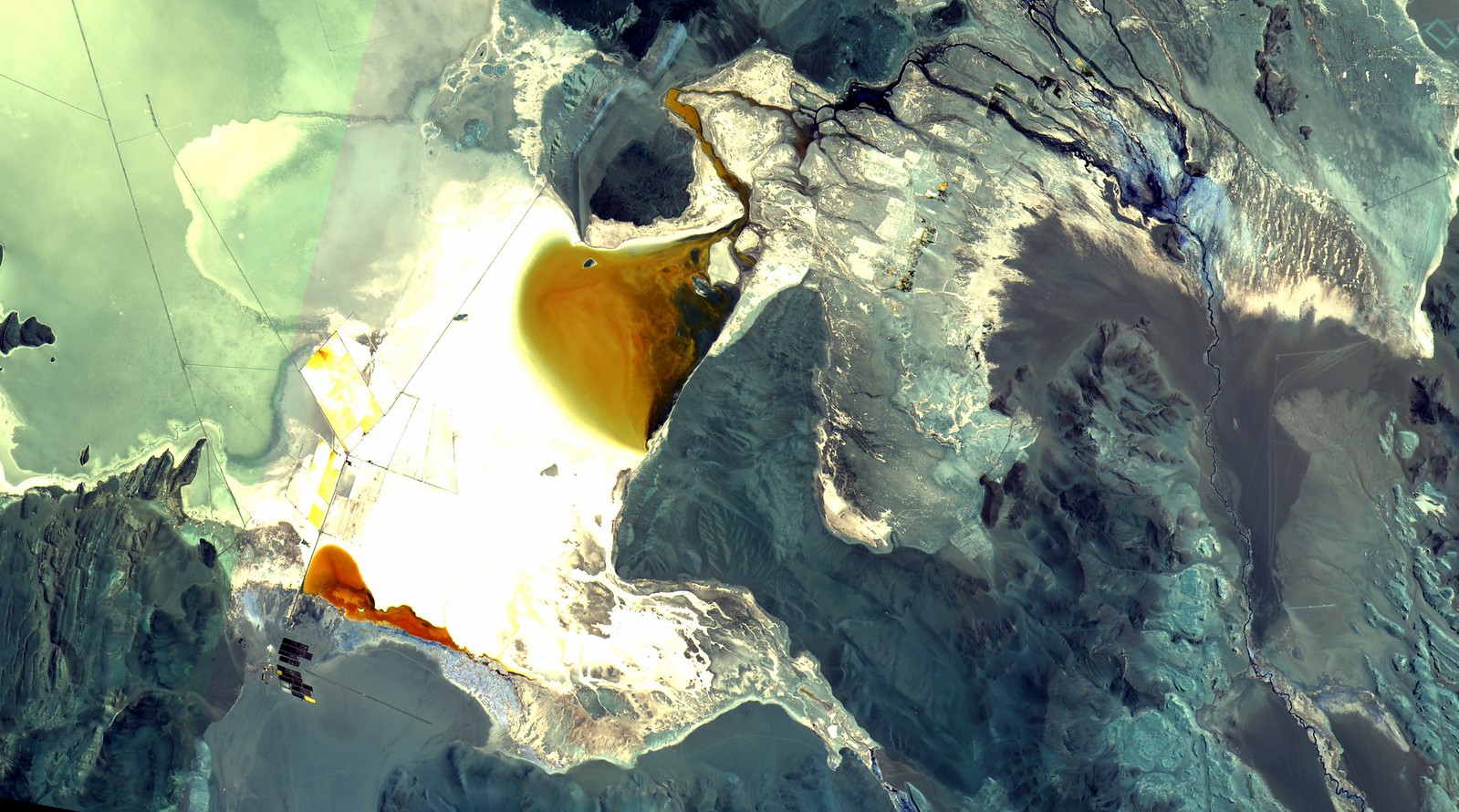

In Salar de Atacama, mining already uses 65 percent of the available water and the area’s farmers find less clean water for their llamas and to irrigate their quinoa crops.. Photo by Oton Barrros / Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra.

Technology is not neutral here. Technologies are artifacts of the social systems in which they sit. Armed with such knowledge, we can interpret technological suggestions as inherently political and reflecting a long history of power.

To cite just one example, the widespread discussion of mass replacement of combustion cars with battery-powered cars is the fruit of private US car manufacturers gutting and preempting mass transit systems. The government subsidized the post-WWII buildout of suburbs — which went alongside dollar-cheap energy — to the great profit of the petroleum corporations that propped up post-WWII governments.

And control of oil meant the denial of democracy in the Arab region. Cars appear “natural” means of transport, in place of, for example, free nation-wide public transit, because of a history of power.

The past few centuries have shown us that the ecologies of rural people are some of the first to suffer amidst the ambition for worldwide capitalist industrialization. Can the GND allow smallholders in Latin America, for example, the right to food and development while at the same time locking in a decarbonized industrial system? Many say yes. But those goals can be at odds. Industrial upgrading requires metals. Metals come from mines. Mines mean cutting into the earth. And cut-up earth means displacement of the people living on that land and the pollution of their water tables.

Batteries needed to power cars use lithium and cobalt. Lithium primarily comes from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and China and extracting it has taken a toll on the environment in each of these places. In China, mines have produced massive fish die-offs and yak deaths. In Chile, lithium extraction requires either massive amounts of water to pump lithium brine to the surface to allow it to evaporate to facilitate extraction, or energy-intensive seawater extraction. In Salar de Atacama, mining already uses 65 percent of the available water and the area’s farmers find less clean water for their llamas and to irrigate their quinoa crops. In Argentina, lithium operations have poisoned streams used by humans and animals alike.

Chilean and Argentinian pastoralists’ and peasants’ lack of social power to protect their water and land is what makes lithium extraction “cheap” enough for large companies to profit from its extraction, and for technocrats in Washington to imagine Green New Deals that rely heavily on new battery technologies. Chile and Argentina, in no small part due to a history of US-backed sub-fascism – the US-backed Pinochet, the pioneer of US neoliberalism in Latin America, against the social democratic Salvador Allende – do not have governments, which could set up a lithium extraction industry, which would actually ensure that the price of this white gold reflected in some way its costs.

Cobalt is not much better. Its primary source is the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) where poorly paid child mining is abundant, with 40,000 children laboring in the mines. Toxic levels of cobalt have been found in the blood and urine of the miners, especially children. DRC, pre- and post-Independence, was a Belgian mining colony. When it elected a national-democratic leader, Patrice Lumumba, who wished to nationalize mining operations, he was assassinated. The massive war, which enveloped the region from 1997-2002, eventually killing over 5 million people, was in large measure about control over resources, including cobalt.

Cobalt’s current price fails to reflect cancers and the human toll in a war practically unknown in the West – because if it did, the technological systems that rest on access to relatively cheap cobalt could not work. They would be too expensive.

Although few deny the ecologically, socially, and politically horrific consequences of mineral extraction, some imagine that it can be remedied without questioning current social, planning, or technological arrangements in a radical way. Others believe that a lot will have to change.

Eco-modernists might call for increasing labor protection for children and examining ways to strengthen environmental protection in the cobalt pits, or even implementing “clean” sourcing requirements for cobalt, that is, no blood minerals. They might imagine that thorium nuclear reactors and clean hydroelectric will soon deliver a cornucopia of clean energy to facilitate seawater extraction of lithium.

If eco-modernists would focus on cleaning up extractive processes, while taking for granted resource-intensive social and technological arrangements, ecological economists would point out that technology, prices, and power are inseparable. The technologies written into plans for future economies reflect certain social arrangements. They are not the result of the mathematical-social ballet of supply and demand curves interacting in a smooth and perfect market system.

Capitalism’s devaluation of nature and human health in poorer countries is not a bug, a dodgy line of code messing up the programming. It is a feature. Seeing lithium or cobalt batteries as an easy-fix rests on not seeing and not valuing many peoples and places.

It also rests — although many would not admit it — on continuing to make development a rare privilege, suitable only for an elite of the world’s population. There is simply not enough ability to bring new mines and factories into production quickly enough, to ensure that the entire planetary population can use the same amount of energy as the US currently uses.

Is there a way to imagine a different GND, a global Green New Deal? I think so. But it might have to start by recognizing the ecological laws of limits and a social ethic of redistribution of wealth and resources, and equality. It would argue for developmental convergence, including in energy use, between wealth and poor, within and between countries. It would respect the red lines from La Via Campesina around biofuels. It would recognize that proposals, which rest on swapping out, clean for dirty technology, which do not account for where the materials for “clean” tech come from, are not very clean at all. And it would have to come from those at and speaking with the bottom of the international division of labor — not just Washington, DC.