The 21st Century is not working out the way many of us hoped: we witness the failure of nations and politicians to address the climate crisis, as well as social unrest in many countries over the failure of a neoliberal economic model that has neglected social equity and environmental sustainability. The Financial Times has even called for “a more sustainable and inclusive form of capitalism.”

To put these aspirations into practice, we could learn something from an entrepreneurial nation of a little over two million people, where the ratio of high wage manufacturing to Gross Domestic Product is double that of the U.S., and 16 percent higher than Germany or Japan. It has the fifth highest life expectancy on the planet (at 83.5 almost five years longer than the U.S.) and exports sophisticated machine tools to Germany and high-tech components for interplanetary space probes to NASA.

No, it’s not Denmark, but the autonomous Spanish Basque Country (Euskadi in Basque).

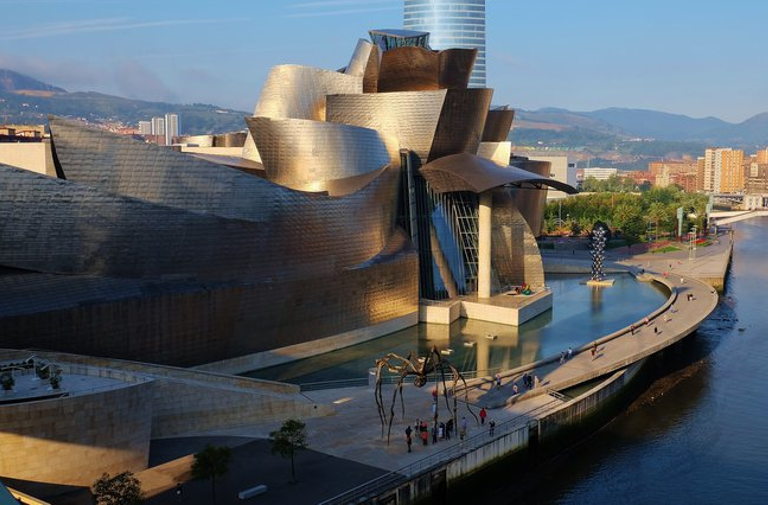

Over several decades Euskadi has transformed itself into one of the most internationally competitive, socially inclusive, environmentally progressive economies in the world. It is a polity that welcomes economic globalization as an opportunity, while reaffirming local community and cultural identity. It has achieved a degree of income equality higher than Denmark or the Netherlands, and a per capital GDP on the same level as Sweden. The Basque Country has reinvented its industrial metropolis, Bilbao, as a model of a post-industrial high-tech economy. Despite inheriting an energy sector heavily dependent on imported fossil fuels, since 1995 it has reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 12 percent while GDP increased 70 percent, decoupling economic growth from greenhouse gas (GHG) increases. A significant part of Euskadi’s world-class manufacturing is organized in workers’ cooperatives, such as the Mondragon Group, the world’s largest consortium of worker-owned enterprises and Spain’s tenth largest company.

The key to these Basque successes is multifaceted: social solidarity rooted in a persistent culture of national and linguistic identity, coupled with a long history of entrepreneurship and trade. Euskadi also benefits from a unique, decentralized, autonomous finance structure where most tax funds are raised, administered, and spent in its three small provinces, increasing the likelihood that social goals are actually implemented, rather than dissipating through the bureaucratic intermediaries of a larger centralized national state.

The recovery of culture and history as tools to deal with globalization

One of the best guides to understanding Basque values is the second American President (1797-1801) John Adams, who cited Euskadi’s legacy of democratic self-governance in a work published in 1787 calling for a new constitution for the United States:

“While their neighbors have long since resigned all their pretensions into the hands of kings and priests, this extraordinary people have preserved their ancient language, genius, laws, government, and manners… Many writers ascribe their flourishing commerce to their [geographic] situation; but…that advantage is more probably due to their liberty. In riding through this little territory, you would fancy yourself in Connecticut; instead of miserable huts, built of mud, and covered with straw, you see the country full of large and commodious houses and barns of the farmer; the lands well cultivated; and a wealthy, happy yeomanry.”

The Basques were already an ancient people in Roman times, and unlike other Iberian peoples they conserved their grammatically complex, non-Indo-European language. During the Roman period and afterwards, when the Germanic Goths invaded the Iberian Peninsula, the Basques governed themselves through customary law and practices known as fueros. As the different fiefdoms and regions in the Iberian Peninsula consolidated to form the Spanish state in the late Middle Ages, the Spanish monarchs pledged to respect the Basque fueros, visiting periodically the Basque village of Gernika (Guernica) to renew this oath underneath an oak tree where neighboring communities would meet to debate local concerns. Over the centuries Guernica became the symbolic ground zero of Basque self-governing traditions and national identity.

Feudalism mostly bypassed Euskadi; Basque culture evolved in independent farmsteads known as baserri, in turn organized in hamlets (auzoa) of ten to thirty farmsteads, with shared community labor obligations (auzoalana). For over a millennium Euskadi was one of the shipbuilding centers of Europe, already incorporating Viking shipbuilding techniques in the 10th Century, and constructing most of the galleons of the Spanish fleet that dominated the world’s oceans in the 16th Century. Near Bilbao is a small mountain of extremely pure iron ore, already mined by the Romans, that supplied an iron and steel industry which provided much of the iron consumed by Britain in the 19th Century. Along with Catalonia, Euskadi was the first region to industrialize in Spain.

Up through the 19th Century the Spanish monarchs continued to respect the fueros, of which the most important was one banning the Spanish state from levying direct taxes. Taxes were collected and spent locally by the Basque authorities coupled with an agreed upon annual sum for Madrid that was periodically renegotiated. In 1936 the fledgling Spanish Republic granted fuller autonomy to the Basques, who established a regional government lasting only a few months before a fascist military revolt led by General Francisco Franco overthrew the Republic. The Basques supported the Republic, and Franco asked his ally Adolf Hitler to unleash the German Luftwaffe in a massive carpet bombing of Guernica on April 26, 1937—a market day when thousands of people from surrounding communities were in the streets.

The Franco regime suppressed Basque identity, outlawing the use of the Basque language, criminalizing the display of the Basque flag and even forbidding Basque parents from giving their children Basque names. Following Franco’s death, a new, democratic Spanish constitution in 1978 restored substantial autonomy—particularly fiscal autonomy—to Euskadi. The Basque government today oversees the Basque Autonomous Region, which consists of the three provinces of Biscay, Àlava, and Gipuzkoa, with a total population of around 2.2 million.

A condition of Spanish entry into the EU was eliminating Franco’s protectionist economic policies. The Basque Country and especially Bilbao (with nearly half of Euskadi’s population) encountered a precipitous economic crisis in which centuries old industries virtually collapsed. Unemployment reached 26 percent by the early 1990s, accompanied by problems such as drug addiction and the spread of HIV. Meanwhile, the terrorist group ETA pursued total Basque independence through bombings and murders of police and Spanish government representatives. ETA only declared a permanent ceasefire in 2011, and announced its disbanding in 2018.

In a period when Margaret Thatcher and others proclaimed “there is no alternative,” Euskadi pursued policies quite at odds with the neoliberal, market fundamentalism that influenced many countries. First, it undertook a comprehensive government industrial policy, in close cooperation with the private sector, to increase high-tech manufacturing in clusters of companies, technology institutes and research centers in areas such as machine tools, aeronautics, automation, transport and logistics, environmental industries etc. By 2005 the Basque country had ten applied technology centers, thirteen research and development centers, four research laboratories, two public research organizations, and three technology parks. Second, it expanded social and welfare services to lessen inequality and promote social inclusion at a time when many countries were retrenching social support.

On these two pillars Euskadi began at the beginning of the 21st Century to promote a model of environmentally sustainable human development.

A legacy of solidarity

By the second half of the 20th Century Basque traditions of solidarity also fostered one of the world’s strongest worker cooperative movements. Worker-owned cooperatives, companies, and associations now account for around 10 percent of all jobs in Euskadi, and 17 percent of exports. Mondragon Cooperative Enterprises was founded in 1956 by five former students of a priest inspired by Catholic and socialist ideals, José María Arizmendiarrieta. Today with more than 80,000 employees worldwide and sales of over 12 billion euros annually, it consists of some 261 separate organizations in 31 countries, of which 105 are cooperatives. Mondragon companies manufacture and export machine tools, telecommunications equipment, computer chips, solar and wind energy equipment, and automobile components, to name a few.

Mondragon and the cooperative movement emphasize that economic development is not an end but a means to human and social fulfillment. Workers are co-owners and the salary differential between the lowest paid worker and highest paid manager in a cooperative can be no higher than 1:6. In Mondragon coops major decisions must be approved by General Assemblies, where all members from CEOs to lowest paid workers have one vote. If a Mondragon cooperative needs to reduce its workforce, the group ensures that workers are retrained and placed in one of the other cooperatives.

But Mondragon and the cooperative movement face increasing pressures to remain competitive internationally. Management has outsourced new production and distribution to affiliates in lower wage countries, and only around 40 percent of group workers are full-fledged owner-members in the cooperatives, located mainly in Euskadi. Mondragon also now includes 143 affiliated companies in 31 nations—including 20 in Mexico and 21 in China, and 6 in the United States. Almost none are cooperatives, so in effect the group has two kinds of corporate citizenship—one, more privileged, imbued with socially progressive rights in the coops, and a second tier of conventional companies in the rest of Spain and abroad.

Moreover, Basque researchers examining Mondragon and globalization found that “managers… are often more committed to efficiency than to the cooperative culture.”

Mondragon’s recent problems may be early warning signs of risks to Euskadi’s deeply rooted egalitarian traditions. Nonetheless, these same values continue to be reflected in initiatives of the government and private sector to integrate environmental sustainability into all areas of Basque society.

Towards an equitable, environmentally sustainable future…

The Basque government has reoriented its national budget planning around the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which sets 17 ambitious social and environmental targets including cross cutting climate mitigation and adaptation goals. It’s established 55 natural protected areas covering 23.3 percent of the region’s land area (compared with 18 percent for the EU as a whole). The current President (Lehendakari) of the Basque Country, Iñigo Urkull, declared that the Euskadi’s commitment to the SDGs reflects Basque values of “auzoalana, cooperation and a shared workload” for the local and global “common good.”

The environmental education programs of the Basque government have been identified by the United Nations as leaders in international good practice. The sustainability curricula of the “School Agenda 21” program encourage students to identify recommendations which they share in meetings with other schools and then present before local mayors and town councils. The Basque environmental ministry has prepared “quick guides” for journalists on climate change and green public procurement, with another on the circular economy in preparation.

Euskadi has established the “Circular Basque network of companies and organizations; already between 2000 and 2016 the Basque economy grew by 26 percent, while the consumption of materials decreased by 25 percent and the volume of urban landfill waste decreased by 56 percent. The Basque Circular Economy Strategy for 2030 aims to further increase recycling and remanufacturing by 30 percent and reduce waste generation per unit of GDP by 30 percent.

Global responsibility at the local level: the Basque climate change strategy

The “Climate Change Strategy of the Basque Country to 2050” (Klima 2050) was endorsed at the 2015 Paris climate summit in Paris as one of the world’s 24 leading public programs for achieving a climate resilient, low-carbon economy. The preparation of the strategy involved comprehensive public participation, including online input through Euskadi’s “open government” website, Irekia.

Klima 2050 aims to reduce Basque GHG emissions by 40 percent by 2030 from 2005 levels, achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, stronger commitments than the EU as a whole, or New Zealand and Canada (though many argue 2050 is too late). Fossil fuel use is be replaced by electric power from climate friendly sources (especially in transport), coupled with comprehensive initiatives in energy efficiency, promotion of cogeneration, “smart grids” and “smart meters” in Basque municipalities, as well “zero emissions” smart building construction.

Klima 2050 will enhance the Basque economy’s international competitiveness. It estimates annual costs for the first five years of 84-91 million euros, more than compensated by 57 million euros a year in additional gross economic activity (including the creation of over 1000 jobs), yearly energy use savings of 55 million euros, and health savings of as much as 32 million euros. The point that many environmental investments more than pay for themselves in advanced economies is one that has been evident for years, but sadly often ignored in politicized debates in the U.S. and other countries.

The Basque success

In recent years Euskadi has soared in international rankings of wellbeing. In 2017 the Basque Country ranked 8th in the EU in per capita income, 21 percent above the EU average, ahead of France, the United Kingdom, Belgium and Finland, and Spain as a whole. The Basque Country substantially outperforms the U.S. in many areas of social and economic welfare, including life expectancy, access to public health services, and income equality.

Euskadi also ranks highly among industrialized nations in education levels, and 26 percent of advanced degrees are in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) areas, double the proportion (13 percent) for the both the European Union and the United States. It ranks near the top of the EU in innovation capacity.

In 2013 Euskadi ranked number four among the world’s nations in the “Environmental Performance Index” developed by Yale and Columbia Universities. Basque opinion polls show virtual unanimity that protection of the environment is “very important’ or “quite important”—higher than Germany or the United Kingdom (both 94 percent). The Basques see no trade-off between environmental protection and economic welfare: 82 percent strongly or completely agree that environmental protection promotes economic progress rather than hindering it.

Conclusion: is another way possible?

Is the Basque case replicable, and is it sustainable? Like anywhere else, there are problems and challenges: Euskadi’s unemployment is the lowest in Spain, but high compared to Northern Europe or the U.S: 9.3 percent (nearly 30 percent for youth under 25). The cooperative ideal faces pressures from global economic competition and the social entropy of traditional solidarity. How will Basque social coherence and values fare in a new era of forced migration catalyzed by climate change, geopolitical instability, and economic desperation in many areas of the world? Euskadi has few migrants compared to the rest of Spain and many Western European regions, but these migrations have just begun.

Euskadi’s cultural history is unique. But similar progressive values are embodied in myriad local legacies around the world. In the U.S. there are many examples such as New England town meetings, or progressive movements of states like New York and California, reflected in California’s leadership in many environmental areas. The U.S. federal system leaves ample fiscal space for raising and spending tax funds at the local (municipal, county, and state) level.

The Basque example is a work in progress, but there is a lesson for all of us: social and environmental solutions inspired by broader national and international policies are sometimes, and perhaps often, best realized through local empowerment and local democracy. A recent comparative study of “Minority Self-Government in Europe and the Middle East” cites Basque environmental progress for showing how “autonomous regions… are more dependent than central governments on long-term investments, while offering a better record of transparency, reliability and political legitimacy.” In the words of former Basque President (1999-2009) Juan José Ibarretxe, “Today, in the ‘global society’ it is ‘the local’ that embodies real hopes that another world is possible.”

I would like to thank Professor Sofia Arana (University of the Basque Country), and Ms. Ixaso Bengoetxea Larringa (former researcher at Gernika Gogoratuz Peace Research Center) for their help in understanding Basque institutions. All opinions and any errors in this article are, of course, the responsibility of the author.