Key Questions

In Part One I made the point that our current situation is unprecedented. Civilizations have come and gone, but this is the first time that the threat to our civilization is occurring on a global level, and the first time the challenges of environmental destruction, economic instability and political failure have all coalesced at the same moment. The nature of the current crisis demands extreme action, not a watered down politically acceptable compromise. It may seem impossible at present, but as the situation unfolds there will be opportunities to make fundamental changes to how we think, to how we live and govern ourselves.

To prepare for that time, we need a vision of what would bring us the happiness and security we crave. We have become conditioned by the ongoing barrage of negative news and the inability of the federal government to take meaningful action on climate disruption. We lower our expectations to a minimal level, to a token reduction in CO2 or a tweak of the health care system. Our leaders need a larger vision than the next election, and the rest of us need to be inspired by their vision so that we can buy into it and become active in working toward it. We need a vision that we can hold on to, that has great promise, even if it cannot be implemented tomorrow or even in our lifetime. In our hearts how do we want to live? What do we want for our children? Where can we look for guidance?

There are groups of people that have lived in harmony with the land they occupy for over 10,000 years, who have developed advanced cultures that met the needs of their people and gave them a satisfying life. Amazingly, these indigenous peoples survived the last 300 years of colonization and white man’s diseases. They survived a genocide perpetrated by direct murder and by forcing the children to attend boarding schools where they had to give up their language and culture. In most cases, the populations were reduced by over 90%, yet they managed to maintain a connection to their cultures and are now experiencing a strong resurgence.

I will focus here on the aboriginal people of the Northwestern American Continent, in part because they developed great wealth but did not use that to control or manipulate the system to gain power or advantage over their fellow tribal members.

Key questions we should ask are: How did they govern themselves? What kept them from exploiting their land, over-hunting or over-harvesting their food resources? What kept them for turning on each other in survival mode when their lives were threatened? These are central questions for our time, more important than how we improve technology to sequester carbon, or extract more resources from the earth. We have dedicated the last 500 years to the latter path and while it has created a comfortable lifestyle for those that can afford it, it has not led to greater happiness, freedom, a sense of security or peace. In fact I would argue that those qualities of life are exactly what we have bargained away in our adoption of the capitalistic values that place wealth and possessions at the top of the list of life goals.

Changing Our Frame Of Reference

We must start from a fundamentally different world view. Anything else, any attempt to arrive at the goal by tweaking the edges of the current ideology, philosophy, or political economic systems will not work. To do so is like trying to turn a bicycle into a boat by putting bigger tires on it. We need to admit that we have been the caterpillar and need to build a cocoon and take the time to metamorphose into the butterfly. We have been conditioned to think of the human race as superior and separate from nature. Our Christian religion supports that position saying that God gave us dominion over the earth. It has led to a sense of separation from the natural world. Our mythology is full of stories that condition us to be afraid of the “dark primeval forest” and of the “creatures of the ocean depths” and of the ocean itself.

The first paradigm shift is to live as an equal with all living beings. There is no ranking; there is no dominion over any part of the natural world. We are a part of the whole living organism, just as the bacteria that live in our gut are part of our system. We depend on them to aid our digestion as they depend on us for food supply. We can learn to celebrate that relationship of give and take, to honor it and enhance it by making appropriate gifts of gratitude. When we do that we no longer look on the natural world as alien or threatening, but as a nourishing mother.

A key word here is respect. Respect for all life, even the parts that in our culture we do not view as being aware, like the plant kingdom, as well as those forms that we do not even acknowledge as being alive, such as the earth itself and the rocks and the rivers. We think it is crazy to talk to trees. At the same time we wonder how the aboriginal tribes learned to use plant medicines that require complex combinations to achieve the desired result. We assume they are like us and had to go though thousands of random experiments and mixtures till they stumbled on one that worked. The aboriginals had a much easier way. They asked the plant.

The other key word is spirit. We lose a whole world of wisdom and joy when we choose to ignore our spiritual nature and live as if we are only physical matter. The aboriginal cultures think of the world as primarily spirit, that we are created from spiritual beings, and in order to maintain our health and strength we need to maintain that connection. It requires a different kind of work and focus. Traditionally, a native youth was required to go on a vision quest to connect with his spirit guide, who would be his companion for life. Without that guidance he was considered only half alive. It was not a question of belief as is required in our religions, or a question of taking the word of the priest on faith. The traditional connection with spirit was tangible, demonstrable and irrefutable.

The indigenous awareness of spirit is reinforced in daily life. Before cutting a tree or killing a deer, a prayer is offered, asking permission to take the life of the plant or animal. A ceremony may be offered, or some other gift. There is a constant awareness that everything has a spirit, even the rocks, so all of it is treated with respect. This relationship with the unseen world is reinforced often with ceremonies, dances and rituals that depict the origin of life from spirit being and the spirit beings that interact with us daily. When I asked “how is this taught to your children?” the answer was “There is no program, no formal teaching. It is absorbed because that is the way we live.” To make that paradigm shift will not be easy for us because it is not modeled in our culture. It must be relearned. There are many people, outdoor schools and books that can help. The awareness is growing and filtering into the larger public awareness.

If we live from the core value that we are spirit beings, then there is a sense of humility that arises in looking out at the world. If nothing is separate, then we naturally live with a sense of gratitude for the continuous gift of life. The combination of humility with a strong identification with the people close to you establishes a ground from which tribal members can look at each situation, each decision from the point of view of what would serve the whole community. In an aboriginal culture, the capitalistic paradigm does not make sense. There is no benefit in gathering wealth at the expense of the rest of the tribe.

Our tendency as part of the Euro/American culture is to look for the technological fix. You may be asking, “What was their governing structure? How did they manage resources?” A native person would remind you that you must embody the mindset and spiritual essence of the culture before the technology will be of any benefit.

Growing Leaders with Integrity, Establishing Trust

That said, to create real change in the mechanics of civilization takes leadership with a vision and a long term global view, someone who can rise above the short term election cycle and the need to get the financial support of corporate institutions. Can such a leader come to power in our democracy? There are some truly dedicated members of congress who have the best interest of the country in mind, but they are paralyzed by the current system that requires them to raise and spend large sums of money to finance their campaigns to stay in office. On the local level, there is a better chance that a leader with integrity can get elected and stay in office.

Leadership in native communities had a different underlying principal since the leader had no coercive power to hold the members to his decisions, no authority to force the collection of taxes, no conscription for an army. He or she had to have negotiating skills and respect to find a common action that all would follow. As a result, leaders evolved by consensus over time rather than campaigning for election.

Some tribes, the Haida and Tlingit in the Northwest for instance, had a hereditary system. The future leader was educated from birth for the role, receiving training in all forms of leadership skills and negotiation skills as well as a thorough understanding of the history, so he would understand why decisions had been made and see the value of them. Even after his training, leadership was not guaranteed. As he was growing up, if he did not fulfill the requirements or seemed in some way unfit, he would be replaced by another, often his younger brother. As an adult he had to earn the respect of the community. If he abused his position he could be removed. This decision was usually made by the older women in the clan, for their role was always to preserve the cohesiveness of the tribe.

Other tribes had differing methods for choosing leaders, but in most there was oversight of the process by the women of the tribe. In the Algonquin tribes there was a formal council of grandmothers whose role was to approve of potential leaders based on their knowledge of the person and his motivation and otherwise fitness for leadership. They also had the power to remove a leader who was abusing his position for his own gain.

Leadership with wisdom and integrity is primary, and the other half of the equation is a citizenry willing to trust and support that leader. On a national level we are long way from that. Again it comes down to fear. We actually have little basis to trust that the current national government has our best interest in mind. In a study at Princeton University which looked at the percentage of legislation passed by congress in relation to the popular support for the legislation, popular support had zero influence on the likelihood of legislation passing.1 In order to trust a leader, each person must have the gut sense that his point of view is heard and matters. It is unlikely that that will happen as long as there is such polarity in government that we cannot even agree that climate disruption is real, or that we live on a planet with limited resources, or that debt matters.

What is required to move beyond survival fear so that we can form a cohesive society? First of all we need a level of security, a trusted source of support that will be there unfailingly. In aboriginal societies, the sense of community and respect for all members led to a practice of insuring that those unable to hunt, the elders, the injured, and the children were fed first when a hunter returned with food. Always the elders were offered the first share, for they were the keepers of the wisdom on which the continuity and survival of the clan depended. The Northwestern tribes were blessed with an abundance of food, so there was rarely a survival situation, but tribes in other locations that were not so fortunate still honored the elders with the first food from a kill or harvest.

We try to accomplish the same end with social security and unemployment benefits, but many fall through the cracks in the system and there are many caveats. None of the social welfare programs inspires the same sense of trust as a local practice among a known community in part because all of them are based on meeting certain conditions and often are temporary. The end result is a higher level of stress and a sense that the government, rather than being an ally, is an adversary attempting to limit or remove the benefits to the individual recipient.

Raising children

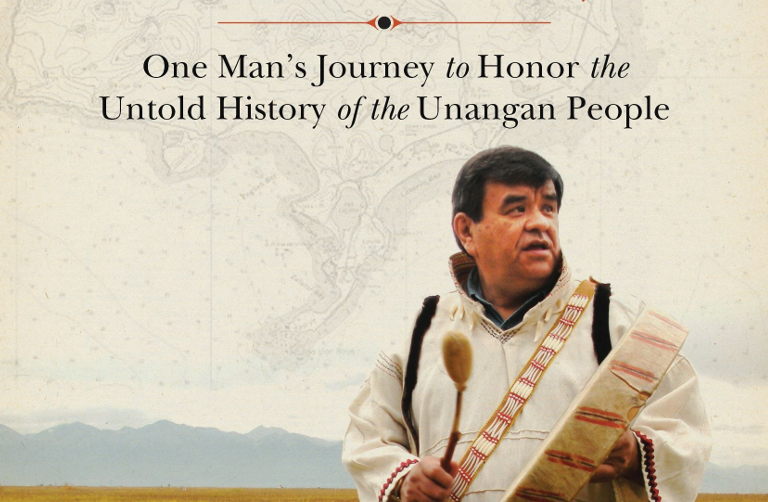

Sharing of food is just one pillar of a strong sense of community. We need to go deeper and look at the process of building that community starting with the raising of children. Illarion Merculieff, an elder of the Unangun People of the Bearing Sea, describes his upbringing as a process of encouragement to follow his own curiosity. He was not given formal instruction. He was never punished for doing something wrong, only praised for what he did well. He felt welcome in every house in the village. The only requirement was that he spend an equal amount of time with women, men, elders and his own age group. He learned by watching and experimenting. The role of the adults was to keep him from getting hurt.2

The result was a young man fully alive, curious and confident of his ability to deal with the world. His sense of himself as part of a community and supported by it was unshakable even as he was sent to the mainland to a boarding school that attempted to “kill the Indian” in him so he would be assimilated into the white culture.

The shift from focus on the material things of life to emotional and spiritual aspects as a source of happiness and well being is crucial. A support for that shift that is underappreciated is the custom of matrilineal inheritances as practiced in many North American tribes. Children came to live with the mother and her brother. The father was busy with his sister’s children. The ramifications of this are profound. The blood bond between sister and brother is permanent. If the mother and the father have issues as couples do today, those disagreements and possible divorce do not have the same impact on the child since they do not involve a split up of the primary caregivers. The child does not fear a breakup of the family and is nourished by the extended family of the mother. If modern psychological theory on child rearing is applied to this sense of a stable nourishing home-life, it could be predicted that the children would have a naturally high level of self esteem and would not need to prove their worth by striving for power or wealth. We may not choose to adopt a matrilineal society, but we can return to a life connected to the community and the extended family.

Connection to the community did not require the loss of individuality. Every individual was treated with respect. The role of the coyote, the trickster, was acknowledged and respected. Strength and endurance was honored. There were many practices to insure that each individual had a sense of their own resourcefulness. One was the tradition of bathing in the river or ocean every day winter or summer to build resilience. They understood that the health of the community and its ability to adapt to new situations was dependent on the creativity and strength of the individual and with each person’s willingness to cooperate for the good of the whole.

Healing Into Our True Selves

The paradigm shift from focus on the individual to a focus on the larger community of people and of the planetary ecosystem requires a shift to a heart centered perspective. Most of us are trapped in the memories of past trauma, or our fears of what might happen in the future. To be free to live in the present requires inner work. Illarian Merculieff describes how this is done. “There are layers upon layers of things that have caused trauma in our lives that are covering our real true self that is in our heart. To get there you have to start feeling all these things that are keeping you away … guilt, shame, remorse, anger and jealousy, all the things that come from the past – and fear that is a projection from the future. Face them, feel them and let them go. The place of power is in the “now”. The Great Spirit is only found in the silence between ones thoughts.”3

- https://www.upworthy.com/20-years-of-data-reveals-that-congress-doesnt-care-what-you-think

- Merculieff, Ilarion, Wisdom Keeper: One Man’s Journey to Honor the Untold History of the Unangan People, North Atlantic Books, 2016.

- Interview with Illarian Merculieff, Port Townsend Washington, May 2019