Global capitalism demands we pretend all is well, while climate and political realities already reveal the end game we are living in. The U.S. government, along with many others in the western world, has lurched into overt authoritarianism, while climate chaos accelerates at a breakneck pace.

How do we live in both worlds?

In this column, each of us reflect on our own process of coping with this existential schism, in hopes that our experiences might be of some help in grappling with the grave dilemma we all share.

Dahr:

Those of us who are lucky enough to be living somewhere in the world where there is enough food to eat, water to drink, and security for us and our loved ones, are living in a bubble.

If we are paying close attention to escalating changes to the climate and the biosphere of Planet Earth, we know that it is only a matter of time until we or our descendants, too, will have our lives turned upside down, or even ended, by catastrophic climate disruption impacts.

Increasing numbers of us are living with the knowledge that it is already far too late to avert a global environmental catastrophe, yet the dominant culture of global capitalism continues to pretend there is still time — or the crisis isn’t actually that bad, or that geoengineering or some other mythically miraculous human technology will save us.

Nearly every experience now feels to me like an example of the growing chasm between the worlds. Here are some recent examples:

- I engaged in a conversation with a friend who spoke of interesting points during one of the Democratic debates, while I paid the debates no attention, since I already see the U.S. as a functioning authoritarian state and wonder seriously whether Trump will be the last president until the final disintegration of this country.

- Earlier today, after reading news of more climate refugees drowning in the Mediterranean Sea in a desperate attempt to gain safety abroad, I walked into a well-stocked grocery store to purchase some provisions, all the while acutely aware of the irreconcilability of these incongruent realities.

- Recently, two of my mountaineering friends and I traversed glaciers in North Cascades National Park en route to a mountain we aimed to climb. Cerulean exposed ice augmented by deep green mountain hemlock lined the valley across from the glacier upon which we climbed with our crampons and ice axes. The wonder and power of mountains brings my soul alight as nothing else. My deep love of this place made the simultaneous knowing of its impermanence all the more acute.

While writing my recent book, The End of Ice, I met with Dan Fagre, a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) ecologist based in Glacier National Park, who is also the lead investigator in the USGS Benchmark Glacier program. One of their benchmark study glaciers is the South Cascade Glacier, which was one valley over from the one I was recently climbing. Fagre told me he didn’t expect there to be any more glaciers in Glacier National Park by 2030, and likely none anywhere in the lower 48 states by 2100.

The hundreds of feet of ice my friends and I were climbing up will likely be long gone before I pass away. My love for these mountainous cathedrals of worship and my sadness about what is happening to them have melded into one simultaneous feeling. It is also why, more than anything else in my life, I want to spend time in and with the mountains and their glaciers.

The pain of existing in this evaporating world intensifies against the backdrop of the rise of authoritarianism across much of the western world, the daily increasing wealth disparity between the grotesquely rich and the poverty-stricken, worsening racism, sexism, mass shootings, misogyny, xenophobia, and a mounting pressure from the global refugee crisis.

I could list dozens of daily examples of this existential and experiential schism borne from being a journalist who wrote a book warning people of the ongoing collapse. These are just a few.

Sometimes I half-joke with friends about our living in the apocalypse. My use of that word stems not from its biblical usage, but from its root in the Greek word apokálypsis which means, literally, “uncovering, disclosure, revelation.”

The veils between these co-existing realities are thinning daily for everyone. Sometimes they are being torn apart. Other times, when people are not able or willing to acknowledge these hard truths, they themselves are being torn apart by this schism.

Carrying this knowledge, how, then, does one live life on a daily basis — going to work as usual, taking children to summer camp, washing clothes, and making meals?

I have found a variety of ongoing actions helpful for creating a milieu with a spiritual atmosphere of acceptance. After years of wrestling with anger, despair, depression and angst stemming from the global crisis, my weekly menu of self-care includes time outside every day in nature, at least one full day a week in the mountains, a daily meditation practice, regular service work for both humans and the planet, and maintaining a small yet tight inner circle of trusted friends with whom I share my feelings about what is happening to the planet.

Additionally, I find that remembering to find gratitude for even the smallest things helps: having clean water to drink, fresh air to breathe, food to eat when I am hungry, and my physical and mental health. None of this should be taken for granted.

Recently I was gifted the opportunity to be of service to my 16-year-old nephew, who joined me for a four-day backpacking trip in Olympic National Park. Knowing all too well the world the younger generations are growing up in, the chance to be of support to him had great meaning to me, and was a privilege and honor.

He, like the rest of us, is troubled by having to live in these two worlds — that of the so-called normalcy of the dominant culture, transposed against the climate/political catastrophe besetting the planet. It was evident to me that this rift was weighing on him, sowing confusion, frustration, fear and anger.

While backpacking along mountain ridges with magnificent views of glacial-clad Mount Olympus, the roar of the river running along the valley floor below us, and the sound of the wind flowing through the forested slopes of the valley, he told me of recurring dreams of the great unraveling he’d had since he was a toddler. Without divulging the details to the reader, I will share what he described as a chronic feeling beneath his ongoing anxiety, one he described bluntly as one of “imminent doom.”

He already knew of the climate crisis, yet asked me to fill in the details. Over the days of our time together in the backcountry, I walked him through my findings from the Great Barrier Reef, the Amazon and Alaskan glaciers. I told him of my time in Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow) Alaska studying the thawing permafrost and venting methane, and of the rising seas in South Florida, and how even the sturdy giant Sequoia trees are under threat. I told him how much of a privilege it was for me to get to go see these places, and how I used the opportunity to say goodbye to many of them, which I expect will likely be gone within my lifetime, and certainly within his.

While the climate news I provided him was bleak, I watched him take deep breaths as it settled in. The truth can be calming, as it sets our feet on solid ground, dispelling the obfuscating mist of lies, deceptions and fossil-fueled propaganda that colors the dominant culture.

My aim for my nephew’s visit was to introduce him to the awe and majesty of the precious Earth, share cross-generational friendship and frankness in order to confirm what his intuitions and dreams had always been telling him, and let him know he always has an ally in me as we both live into the future.

When he departed to head home, he thanked me and told me he wanted to come back next summer. I reminded him that, no matter what, I’m always here for him in whatever capacity he might need me in the future.

Barbara:

As I write this piece, I am looking out the window, across a welcoming meadow, with my dog snoring contentedly at my feet. That’s my immediate reality.

Parallel to this, on August 2, 12.5 billion tons of ice melted on the Greenland ice sheet; the 250th mass shooting in the last 215 days in the U.S. just broke into the headlines; 200 known species went extinct; and the equivalent of 4,300 football fields was razed in the Amazon. This registers in me as a cocktail of outrage and grief. Steady background anxiety translates into a premonition of collapse on interlocking fronts, mass chaos and human civility gone haywire.

Behind the disparity of my privileged immediate experience and the knowledge of what is coming, are two very different ways of thinking. In a semblance of control and cool observation, my mind witnesses, assesses and wants to fix the crises. It’s my ceaseless effort to frame what is going on and keep it manageable in my head.

Parallel to this process, after years now of digesting scientific climate realities, my body, heart and subconscious anticipate what is in the wings. Uncertainty prevails despite any efforts to contain it all.

What do I trust as the basis for my actions and choices? My mental context feels thin and brittle. My perception through my body senses is increasingly loud and demanding. I have the choice of where to place the weight of my discernment. Increasingly, I am using my “figure-it-out” capability to concretize the implications that arise out of a deeper level of perception mediated by my heart.

The pressure of sensual perception shows up in many ways.

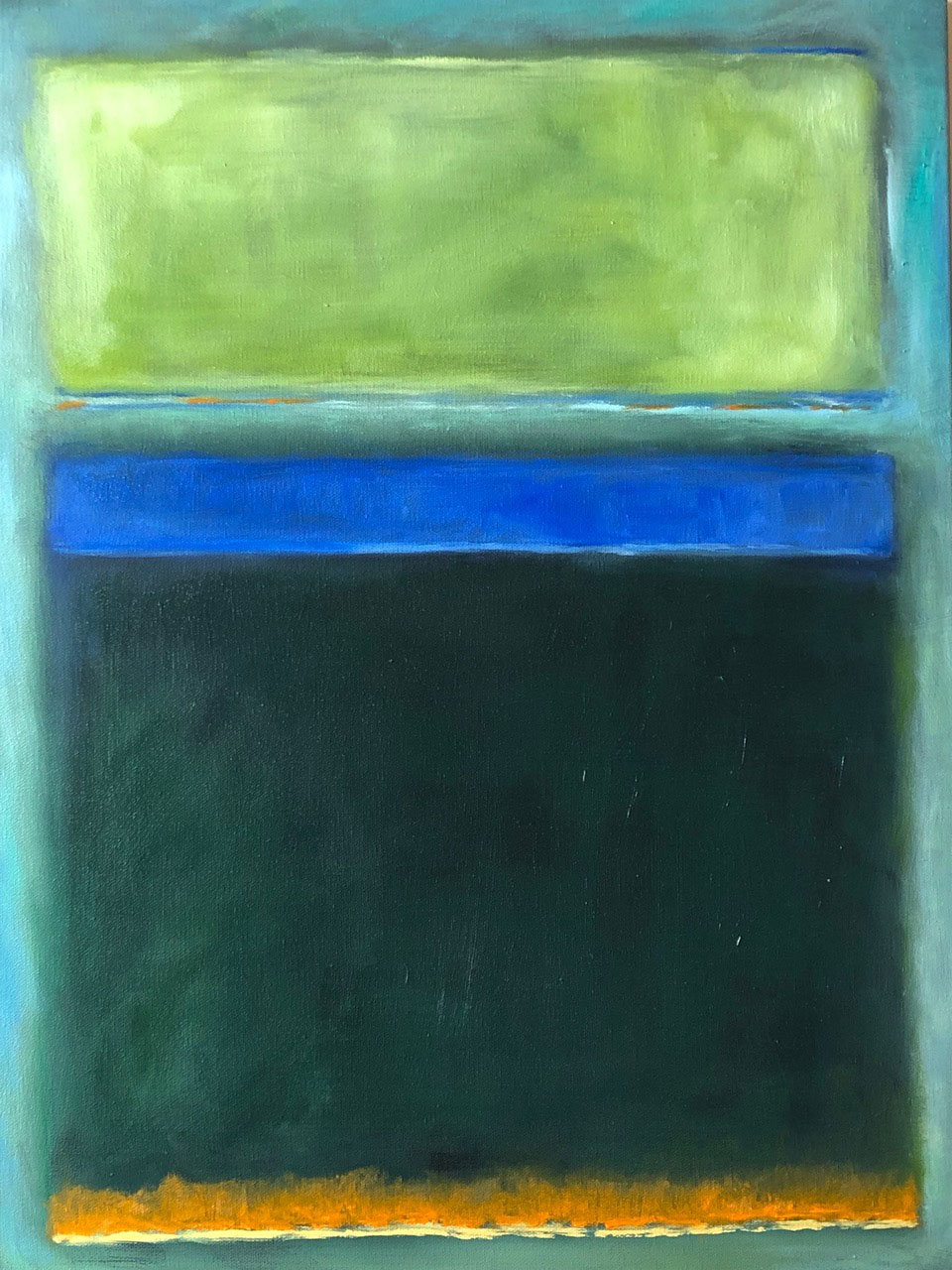

I am an oil painter, and for the last 20 years have immersed myself in representational art … paintings that look like something that viewers can identify. Now I can’t do anything but work abstractly, faithful to momentary impulse. The great color planes that emerge on the canvas are not of my choosing; they are the expression of a deeper hand that is persistent and thematic. A friend noticed recently that complex dark swaths of color sit at the base of illuminated pigment toward the top of the canvas, perhaps connoting a clarity of the human spirit that persists behind prevailing darkness. I am respecting what my subconscious is conveying, though I don’t have concrete interpretations as of now.

Painting by Barbara Cecil.

Along with Dahr, I live in an area in Washington State that is crisscrossed with emergency preparedness efforts, as this is a prime earthquake zone. Recently I had a strong urge to get my food supplies in order. It turns out Dahr had the same impulse. Both having gotten the same memo, we piled into his truck and drove to Costco — a nightmarish place for me, but it made sense. He shoved one of those oversized carts into my path and we cruised the aisles in good spirits. No fear, just following orders, now replete with one month’s fare to tide us over should the need arise. For both of us, it isn’t just about earthquakes, but something in the wings that cannot be named. The preparation felt simply right, and even-keeled. It was an appropriate emotional and physical response.

I have thought often in the last years about what I call “Noah Moves.” Most people probably thought Noah was outlandish at best, building that ark in the desert. I imagine he felt rather isolated in his determination. But he followed his inner guidance. Things that we are called to do often don’t make sense to friends, colleagues or family … from buying a mountain of food at Costco, to moving, to rearranging patterns of relationship, to laying in protest on a bridge in London. I am continually answering the question, “How, then, shall we live?” according to an inner standard that registers direction moment by moment and day by day. I am learning, often ungracefully, by trial and error, how to bridge gaps between myself and the people I love who are navigating in a different reality.

I recently received a letter from a professor, Aurora Winslade from Swarthmore College, who is in charge of a national sustainability network at universities across the United States. She was asking for emotional and psychological resources that could help her come to terms with the reality of our times:

I host a workshop/retreat for sustainability professionals each summer, and this summer we incorporated various attempts to explore the crisis that is unfolding around us and how we feel about it, and I found that many (most?) people there were going through serious emotional trauma as they tried to continue to do their day jobs of tirelessly cheerleading for incremental change, while (almost secretly) harboring increasing feelings of impending doom.

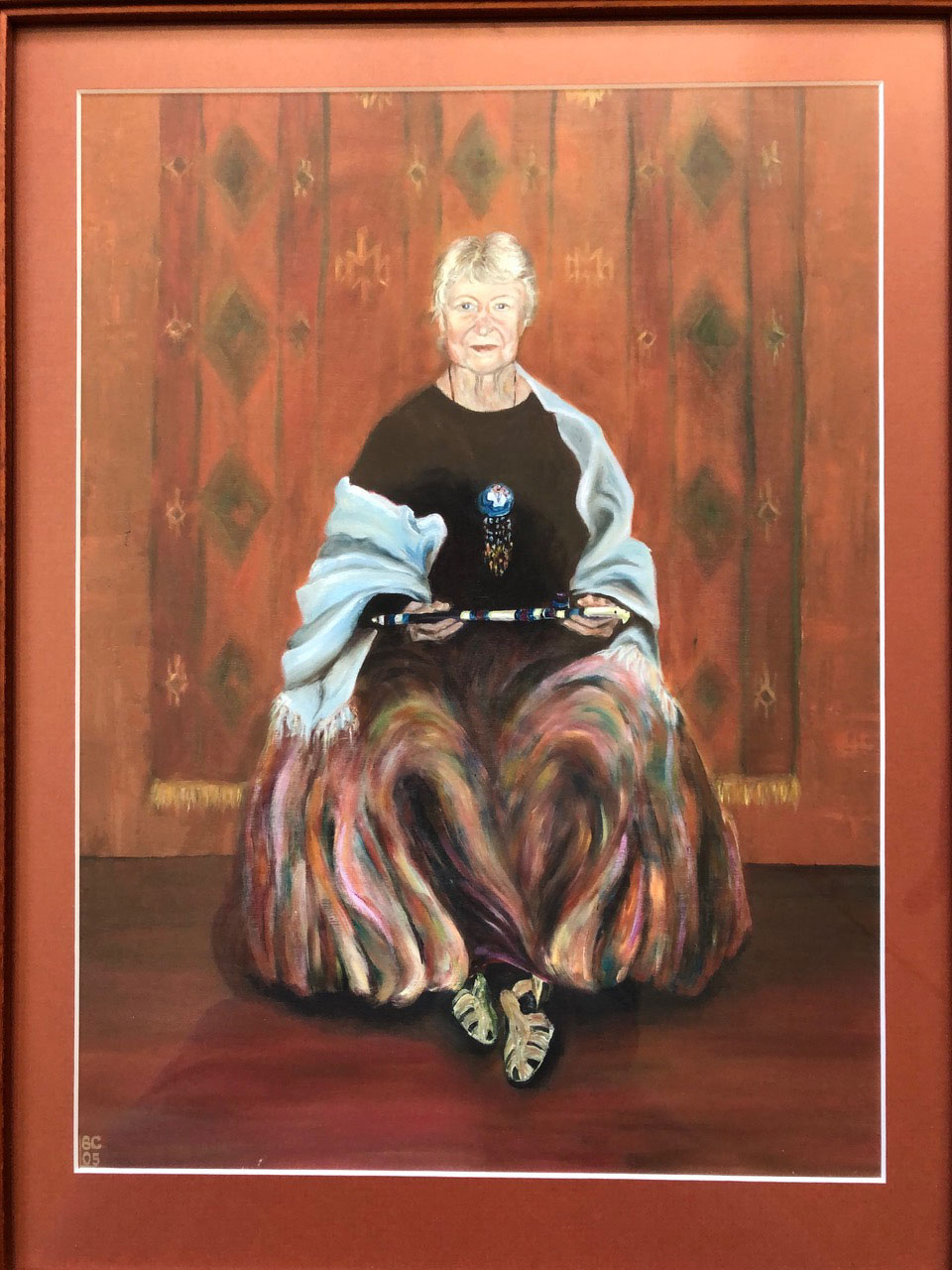

Painting by Barbara Cecil.

Dahr and I write these reflections to help bridge this widening gap. I have deep compassion for activists who are entertaining the fact that it may be too late for all efforts to stem the tide. My integrity, well-being and a greater moral imperative demand action that is relevant now, as scientists’ worst-case scenarios are regularly surpassed.

My activist friend, Vicki Robin, whose ferocity and brilliance have been beacons for me for decades, including her advocacy for local food consumption, revolt against the Navy’s infringement on human rights in Washington State, and wisdom around deep change in our patterns of consumption, describes herself as palpating the walls in a dark room, looking for a light switch. She penned a poem recently as a way of describing her split between the two worlds. To me, it reads as a passage beyond the disparity that has been tearing at her for many months now. Here’s an excerpted version:

Reflections While Doing Dishes

I will be useless in the end times because I’ll still be saving rubber bands in case someone someday needs one.

I’ll be useless because I’ll still be rinsing out plastic bags in the sea as the water rises.

With the last gallon of gas I’ll still be gliding to a stop in order to go just a little bit further.

Once the gas is gone I’ll be thinking of something useful to do with the car.

The habits grooved deep in me as rituals of giving a damn will keep on precisely because they are habits.

I will be one of those wispy haired disheveled old women with a toothless smile calling everyone dearie and honey

and seeing if I have something in my pocket for them.

It’s too late to change everything, my friends.

So let’s save rubber bands and plastic bags, let’s empty our pockets,

let’s fight for what’s right not because we will win (and we’ll want to) but because it’s just what we do.

What do I change now that the change has come? Perhaps only my expectation that we could change this in time.

I am not hopeless. I am only without the hopes I had.

I will fall silent soon as life grows resplendent with truth.

My days are still filled with serial shocks to my worldview and identity as I slowly come to understand more deeply how we got here, and what my part is in it. I bear witness and follow an inner thread. I believe that each of us is built to heal, restore, release, recreate, remember in our own way.

For me, I am making amends to this planet through all the ways I relate to Mother Earth. I am searching for new language to clothe an unprecedented juncture in time, and bringing that new language to these pages. I am finding ways to be an ally to Indigenous people who have long led — and continue to lead — the way in protecting and nurturing the Earth. And I am stepping up beside the young people who are on the front lines. Almost daily now I get on my hands and knees, and lower my head to touch the ground. This gesture, I realize, puts my heart above my head, telling me what to follow.

Teaser photo credit: BARBARA CECIL, LANE V. ERICKSON / SHUTTERSTOCK; EDITED: TRUTHOUT