Gaby Gonzalez is a soil scientist, an architect and a third-generation Mexican farmer, descended from a proud campesino grandfather and schooled by her father in the ways of modern industrial agriculture, an approach she found seriously flawed. The lessons she learned from both of them found a new meaning when she discovered biodynamic agriculture. Last year, she was part of a group who founded the new Mexican Biodynamic Agriculture Association, Impulso Biodinámico de México. She took a little time with us recently to share a bit about her journey with this deeply spiritual approach to cultivation.

Esperanza Project: How did you first become interested in biodynamic agriculture?

Gaby: As a child I observed the most natural ways of growing food of my grandfather, who would heal people with plants and animals. There were always people waiting for him at his door to come to consult him.

My grandfather was a criollo or creole, a native Purepecha and Spanish mix, a healthy brown-skinned worker of the land who knew his pace and rhythm. He was always busy, at home on his farm near Zamora, Michoacán, making cheese, fermenting something, fixing his tools or creating new ones. Most of the time he had something in the fire, boiling, cooking, roasting.. Most of the time he was in his “zaguan” — the back part of the property, beyond the orchard where the animals were kept — where he used to prepare his remedies and kept insects and fungi in alcoholic solutions in order to extract their potent qualities, which then he used to prepare the remedies; he used scorpions, wasps and bees, grasshoppers and other insects as well as all sorts of herbs such as quelites, pasiflora, ecuares, chayotes, and many roots and fungi. He knew every inch of soil of his ranch, every bird and plant that would come back with each season. In Zamora, where my grandfather was from and his ranch used to be, the land was fertile, water was abundant and it had blessed weather most of the year, sunshine and loads of rain during the season. Of course, some 40 years ago, his approach was typical of the farmers of the day, although few had his distinctive gift of deep contact with nature and the capacity of understanding its inherent but subtle language. He understood the equilibrium in health. Little mattered if it was a plant, an animal or a human; he knew that equilibrium was key. He understood the qualities of each realm and used them to create remedies to rebalance the deficiencies of one with the other. Serene, serious but content he did his job to create a timeless and always effective way of working with the land, plants, animals and humans.

At the opposite extreme, my father encouraged the perspective of chemical agriculture when he took over the ranch after my grandfather became ill.

My father took the reins of said ranch to produce “properly”— that is, with chemicals; as with many families, young people consider their parents’ ways of thinking and doing to be obsolete or inadequate, and the knowledge they’ve acquired in their studies to be far superior. So, my father took over the ranch when I was still a child, but I remember very well that from the first year, the ranch never produced enough (as if it were the soil’s fault, our not knowing what it does); consequently, after five years, my father and his nine brothers decided to sell the ranch.

The way the soil was forced to produce exhausted it to the point that it no longer produced enough to live on. My father, driven by his will to overcome the power of nature with chemicals and his certainty that this was the right way, couldn’t see a different way to work with nature, rather than against it. Observing his battle with the elements clarified my perspective on agriculture, and I kept looking for alternatives.

Today my grandfather’s farm is a 60-hectare concrete slab with a subsidized housing project on top.

So in the bosom of my family I discovered these two paths. And I realized as a child that, if I was going to do agriculture, I would not do what my father did, just as he did not do what his father did. The difference in my case was that I knew the advantages and disadvantages of both visions. So, I entered into the world of “organic” agriculture and began to learn, to read, to practice.

My family processes fruit industrially, so the quantity of organic waste is huge, and everything goes to the municipal sanitary landfill. At the age of 15, when I understood that it was a huge problem for large volumes of organic matter to be thrown away, I proposed that something be done with it. My family told me that they would not bother to do anything with the “garbage” because it was “garbage,” but that if I wanted, I could investigate what to do; so I did.

For the next 15 years I studied, worked, traveled, and got to know projects and teachers that introduced me to the vast world of composting.

I travelled to Europe when I was 17, to Belgium, and observed the way they manage waste. In England I visited a farm that used to compost. I went to Australia and discovered permaculture and new ways to regenerate land, also through composting. Teachers who marked my path included Angelika Lübke and Urs Hildebrandt from Austria, Jairo Restrepo Rivera from Colombia and Darren Doherty from Australia.

Following up on my experience with my family, I decided to develop an industrial composting project with fruit waste from agroindustry. This project introduced me to a series of spiral turns that would end up changing my perception of life, my way of thinking and my way of living, and brought me closer to what I consider today a life mission.

At the moment I decided to embark on the development of this project, which was in a few words a double doctorate in soil science, life conspired to make it happen: I found close at hand all the tools and people necessary to achieve it. One of these tools was Biodynamics, a discipline I not only found fascinating, but to which I owe the person I have become.

Gaby’s first composting business, Compostas del Duero,in Zamora, Michoacan.

What impressed you so much about Biodynamics?

Gaby: Maybe it wasn’t so much the What that impressed me, as the Why … I met Lübke and Hildebrandt at a composting course in Valle de Bravo in 2012, then traveled to Austria to see their work — which was the last piece of the puzzle I had been waiting for to move ahead with my composting project. My Austrian teachers had introduced me to the term “Biodynamics” with a somewhat critical view of the method I had learned of composting. I had a very narrow and counterproductive idea of what Biodynamics was, for what at that time was my goal: high-quality composting as a large-scale soil regenerator. At the beginning of the project I read about the fertility of the Earth in German soil scientist Ehrenfried Pfeiffer’s classic work, and of the multiple experiments that were carried out by Lilly Kolisko to interpret the biological processes and demonstrate the importance of life in the soil.

I understood that between both scientists there was a conductive thread that remained invisible: Both used Biodynamics as the basis for all their experiments and subsequent books that today are foundational works for how to practice agriculture in general. So I understood the importance of Biodynamics in life: that not only plants are important for high-quality production, but also the soil, the animals, the elements, the environment, everything that happens around us that allows us to be alive. That understanding of “globality” changed me completely. I began my immersion in the depths of Biodynamics, and I went through many phases of disbelief, of feeling frightened — I felt a resistance to changing the Western science-based approach for such abstract and open ideas delving into the vastness of vital processes. I began to question the whole concept of rationalism itself, where we think in a rational way, trying to find answers that are short-sighted and creates square concepts of things, not letting the thought or idea develop itself into different and more organic ways, to open up into different forms to understand, to feel, to experience deep inside of the self that you know something, rather than think something is right because of what you have been taught. I felt frustration and reached a point of renunciation. I finally came to the books of the Austrian scientist-philosopher Rudolf Steiner, the founder of the biodynamic approach to agriculture. I read Theosophy first, then the farmers’ course and then the works continued to flow into my hands and I had no intention of letting that flow stop.

This is how I came to know that Steiner lays out an entire approach to the task of being human in this world, granting us the title of stewards of the Earth based on this uniquely human capacity we possess: the power of thought capable of evolving.

So Biodynamics not only brought me techniques to produce healthy food; it brought me the possibility of developing healthy thinking, to lead a healthy life and that the impact that this life has on the evolution of human consciousness, elevating me beyond what was simply given to me at birth. That is what inspired my deep interest and respect for the practice of Biodynamics and its sister disciplines: Waldorf pedagogy, Anthroposophical medicine, Anthroposophical architecture, philosophy, and so forth – the human task in its totality.

Photo: Facebook/Impulso Biodinámico de México A.C.

Esperanza Project: What is the difference between Biodynamic and Organic Agriculture?

Gaby: As I learned from observing my father, modern agriculture focuses on producing healthy plants, as isolated elements of the environment and with all their needs to be manipulated in order to produce adequately; that is, today’s agriculture considers the capacities of nature to be insufficient to produce with the quality and quantity that we have achieved with industrial agriculture. Organic agriculture is simply the opposite extreme of chemical agriculture; chemical inputs are replaced by organic inputs to nourish the plants.

Biodynamic agriculture, as the word implies (bios = life, dynamy = movement) is based on the understanding and study of vital processes. In this case, we focus on agriculture: on food production. Biodynamics observe the processes that give a plant the possibility to grow and develop, that which gives life itself to plants. It focuses on understanding the intelligence that exists behind the growth of a tomato plant, or a carrot or potato; What is it that makes it a tomato, and not a potato? How do you recognize the key moments in a plant’s development? What is its language? Who do they communicate with? What do they take from the ground? What do they take from the air? Why is the root a root? Why are the leaves leaves? What happens with the sap? Why in the day does it “act” in one way and in the night, another way? What happens with the different seasons of the year? With the moon? … Thus, this observation of a simple plant leads you to observe the rhythms of the cosmos and the depths of the Earth to give you a small idea of what it means to generate a tomato.

The main difference between Biodynamics and the concept of agriculture in general, whether chemical or organic, is that in conventional / organic agriculture we consider these fruits as isolated elements and / or as objects. We take for granted everything that Nature has done for millions of years, and the fact that we do not really do anything, other than intervene in these natural processes, breaking with a delicate balance that now forces us to intervene with our inputs to conclude that this is just how plants are, that’s the way agriculture is — and therefore having a tomato today and still having enough tomorrow is enough, because we have decided to produce them.

Those of us who work with Biodynamics make the effort to understand and potentiate the processes that keep alive, in the context of agriculture, the plants within their environment and all that it implies. Thus, quality production is valued from another perspective, not only quantity; Intervening wisely to successfully manage environmental processes and understand the language that these plants use to obtain what they require from their environment in order to develop and produce.

Esperanza Project: Can you share some specific examples where you have seen that this approach has worked well?

Gaby: Biodynamic farmers are producing all around the world. Biodynamic agriculture, which as a discipline came into being scarcely 100 years ago, has spread throughout all continents. Today, India has more than one million biodynamic projects. Europe and North America have established valuable commercial networks for biodynamic producers, and in Mexico every day more producers are added, for better or for worse, thanks to the great crisis that is currently being suffered in the fields. We are seeing climatic changes and abuse in the use of agrochemicals that weaken the environment, as I mentioned before, and intervene in the balance of its vital processes, altering them and finally causing the collapse of the means of communication between plants and the environment. So in Mexico today, biodynamic projects are joined to soil regeneration strategies where the word biodynamic as such is widely known, but is growing rapidly in all areas: production of grains, fruits and vegetables.

In Mexico, through necessity and responding to calls of distress (the main productive regions of the country are in serious problems), people are seeking possibilities to stay afloat with new strategies, and biodynamics is, today, a kind of life preserver that they are turning to as they seek help, little by little.

In Chiapas, for the past 90 years, there has been possibly the first biodynamic project in America, Finca Irlanda, where German immigrants who traveled in search of suitable environments for the production of biodynamic coffee have been living since 1928; they established the farm after attending the lectures on the course for farmers by Rudolf Steiner, in Koberwitz in 1924, from where Biodynamics as discipline occurred. The operation is a clear example of success today as it is still standing and producing one of the best coffees in the world; even with the pressure of the collapse of many coffee plantations that have succumbed to the devastating rust plague that has affected a large part of the coffee-growing region of the country, among which are many conventional and even organic coffee farms.

I moved to San Miguel de Allende in 2017, after putting on standby my compost producing plant, Compostas del Duero. I had learned a lot from that experience; it was enormously popular, but we didn’t have the space or the money to expand quickly enough to fullfill the demand, which would have helped us to break even. I hope to revive it in a couple of years, but meantime have begun working on the development of a biodynamic composting project near San Miguel at a biodynamic asparagus ranch, to learn more and to put all that I had already learned with Compostas del Duero into action again. The project is growing with wonderful results in the field, in the mentality of the people who work it and with the final result being the superior quality of the asparagus that is being produced there.

Photo: Facebook/Impulso Biodinámico de México A.C.

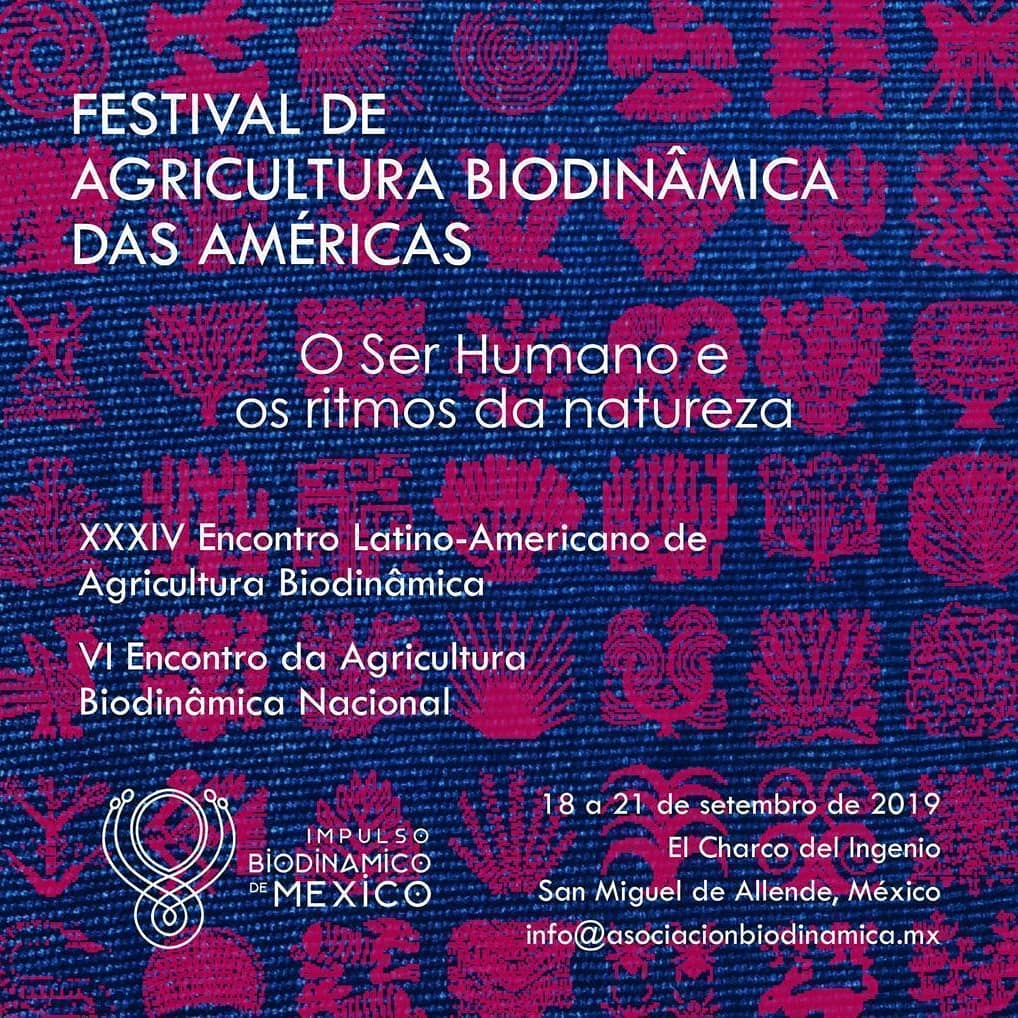

In October 2018 we formed the Mexican Biodynamic Association — called Impulso Biodinámico de México AC. — a biodynamic educational association that has already been recognized within the international federation of biodynamic associations (IBDA). We are working to disseminate honest information throughout Mexico through digital and physical literary resources translated into Spanish, quality consultancies and approaches to marketing networks to help the country’s biodynamic producers to promote their products; we seek to create international links with other projects, associations, institutions and foundations and to promote new biodynamic projects in Mexico. We want to promote the development of pilot projects and demonstration and educational centers for the training of biodynamic producers. I encourage young people to reinterpret learned agricultural concepts, to look for new creative ways to involve everyone in a new approach to restore our natural environments that keep us alive.

Esperanza Project: What is the connection between Biodynamics and traditional indigenous agriculture?

Gaby: What they share is a basic cosmovision or worldview, an approach that acknowledges the connection with a whole. In Mexico, for example, it is well-known within the Wixarika tradition that, by idealizing certain natural elements of its semi-arid environment, certain plants or animals, such as their gods, maintain a connection with the sacred, beyond the concept of minor rank that humans give to a simple plant or a simple animal; because these beings, by becoming medicine and food, keep us alive within the sacred aspect of the intangible that is that relationship with the whole.

That which keeps us alive has that indecipherable, mysterious, sacred aspect within our subconscious; as human beings, whether we express it or not, whether we agree or not, we all know it exists inside us. That subtlety is what Biodynamics as a current discipline has in common as a philosophical aspect with indigenous cultures and their worldview. Biodynamics requires that way of thinking in order to permeate the Human Being and his work with nature.

To be clear, the techniques of cultivation and production are not original to the indigenous cultures; they are created, and have always been changing and evolving. The current agricultural processes by which we obtain food on a large scale have nothing to do with connection, or with life processes, and much less with understanding it as something sacred. The word Agriculture lacks culture in reality, which is what gives meaning to the connection between the indigenous worldview and biodynamics. Biodynamics, as a modern technique, rethinks agriculture in all its concepts, integrating the culture of life, something bigger than we are that we must honor, with techniques and processes that support life. Thus indigenous cultures have their rhythms for planting corn and beans, for each crop that keeps them alive within their environment, and thus they can visualize what works for them, to improve their crops with the passage of the years, observing, feeling and understanding the natural processes through which these sacred plants pass that keep them alive. And becoming resilient and independent, some concepts that conventional agriculture don’t like at all and of many people are even afraid of.

Esperanza Project: What kinds of obstacles have you faced in this work? How have you overcome them, and what has surprised you along the way?

Gaby: The most important obstacles have been my own internal processes, healing and finding the possibilities to open my mind and my heart to what nature has to teach me, not the other way around. The process of unlearning has been constant and challenging at all levels. It is always complex to break your own schemes to try to understand something bigger than you. Human schemes, created to constrict, wear down the spirit and obscure thinking by covering it with veils of dogma, recognition and titles of power or professional standing. The ego is a necessary tool to walk through life, so I see it and I believe, as long as it is not the only navigational instrument that I know how to use.

The possibility of descending from the ego to the heart melted many walls for me, but it opened wounds that I didn’t even know I had, and it has been important to face them. In addition to what one personally crosses by choosing a path of flexibility (of the mind, heart and ego) that is not easy to carry out in this world of rigidity and structure; the most complicated has been the social barrier that always pushes us back to that rigid and structured path, to the status quo, to the lifestyle, to the difference of genders, etc.

Biodynamics certainly not only challenges your mental concepts, but the social constructs and the limits of human potential. You become an alchemist of consciousness, in which finding the way to turn into gold what crushes you is the same process that allows you to open your perception to enter the agricultural biodynamic practice. But it is going against the current, always — although there comes a time when you stop fighting, that you do not go with or against, you simply are.

That is how I have learned to cope with the ups and downs of one’s path, of what each person has the responsibility to learn in the life that falls to them. Knowing and confirming that nothing is forever and new challenges always come. The biggest surprise is to realize that with each experience, I gain more resilience and become aware of it — and that gives me strength and tools for the challenges to come.

With biodynamics, the path is personal. The more you advance in yourself, the more you become healthy, the more you allow yourself to experience your inner self. More profound are the possibilities of establishing a relationship with your environment that gives you what is necessary to restore it and produce more and more vigor, more life. This concept has become a major obstacle for conventional agricultural producers, immersed in the role of being the protagonist, the one who produces, the one who makes the plants produce. This biodynamic way of thinking, which is related to the dynamics of life in all aspects, is something so deeply disconnected from the Human Being at present, which is the biggest obstacle to becoming truly Human and taking on the true role that corresponds to us.

Esperanza Project: What are some common misconceptions about Biodynamics?

Gaby: Sometimes it is misinterpreted as organic agriculture, as a task in which you seek the recipes to add nutrients to the plants. It is interpreted in all the superficiality in which we live, in the rapidity with which the results “should” be seen as to whether this technique works or not.

It is known as something that doesn’t work because it is “slow,” or because “I won’t be able to produce as much”, or “because I will lose money,” etc.

Because it involves a lot of work. Maybe at the beginning, when making the change, yes, you have to do a lot of personal work as well as work in the field; clearing one’s own space, what has not been touched internally, requires a complicated and long process, certainly. First, you must clean up the abuse of the ecosystem, the excessive use of agrochemicals that for years were used to exploit the intrinsic potential of nature to produce; it takes time to reestablish an ecosystem and its processes take time, but it is our responsibility, and at a given time we will have to do it. In Biodynamics, the investment of work is opposite to the proposal of modern agriculture; we work hard at the beginning in order to rest at the end, obtaining as a result of that work a restored and resilient ecosystem from which we can survive the rest of our lives in peace. In contrast, modern agriculture emphasizes rapidity, superficiality and exploitation. Beginning with a healthy ecosystem, agriculture requires little work; but as time passes and the land degrades, the need for human work intensifies, concluding with a dysfunctional farm that no amount of work can rescue, and a collapsed ecosystem. A sad situation.

Also, people tend to misinterpret what biodynamic techniques imply. One of the biggest misconceptions revolves around the use of animal parts. The biodynamic preparations are, as the name implies, prepared out of the three realms of nature on this planet (animal, vegetal and mineral). The animal composite mostly used for biodynamic preparations are cow horns, for example, used to make the “500-horn manure” and “501-horn silica” preparations. Other animal organs and tissues are used for making different preparations. Each animal part has a counterpart in the life force spectrum, regarding the cycle of nutrients, of basic elements that links directly with a living process of the animal, hence the use of the bladder to recall the inherent process of nitrogen within the animal life, for instance.

This practice has produced a negative, or abusive or even dirty, disgusting connotation, and that goes against the thinking with modern agriculture, since nothing animal should be used to maintain the “innocuousness” of the crop, according to this philosophy.

As an environmentalist and opponent of the inhumane treatment of animals, my initial response to these practices was negative as well. But then I learned that a cow is the greatest alchemist of all within the animal realm; hence most of the parts used in biodynamics come from the cow. I realized that using a cow just to eat it is diminishing its possibilities to fulfill its role in the ecosystem, to pass away into a superior self — a realm we tend to envisage for ourselves only, exclusively human. When we use the cow organs to create another alchemical possibility to transform and reconnect ourselves through them with honor, we are perceiving the life of the cow in much the same way that an indigenous culture acknowledges that the lives of the wild animals is what keeps them alive, so they honor the animal’s death in a ritual killing.

Returning to the idea that cows are the greatest animal alchemists, that’s the kind of ritual we honor cows with, their existence, their life purpose, to help us reconnect ourselves with the whole through making those preparations and also liberating the animal spirit back into this whole. The vegetal and mineral components contained and/or wrapped up within the organs transforms with the potency of the flow of life forces that surround us. By making these preparations, an animal part becomes the “chalice” for the transmutation of something dead into something greater to ignite life again — thereby liberating the animal karma we’ve been creating throughout our relationship history with animals. I came to see that it’s a beautiful way to look at it, once we see the beauty as well in the destructive nature of life itself. From that perspective, we make sure that the animal parts used to make these preparations come from animals that were treated with honor from the moment they are born to the moment of sacrifice.

The irony is that some discriminate against biodynamics for being for “hippie” and others discriminate because they consider it elitist. So it is clear that there is a counterstance on each side, simply because the methodology of biodynamics is completely different from what we know, and many of us are reluctant to explore the unknown.

Esperanza Project: What is your vision for the future?

Gaby: I’m excited about our plans for Impulso Biodinámico de México, a new association of people interested in restoring a possibility for a healthy future in Mexico, and the world, since a biodynamic association exists in most countries around the globe. In Mexico, we are linked to ancestral knowledge that has helped us until now to overcome the terrible possible scenarios for a desertified future. Thanks to indigenous minds and hands our seeds of medicinal herbs, “hortalizas” and grains have led us to this moment where we, as a biodynamic group that acknowledges the path from where we come as well as the new ways of seeing and working with nature, will try to then intertwine and reinforce the practices in order to foresee a brighter future.

The association will be focused on spreading this knowledge on biodynamic agriculture, in helping the project to grow, in linking farmers to markets, in creating new possibilities to experience agriculture and in seeking to promote the evolution of the human race with honor and responsibility. We hope people get interested more and more and become members of the association to support the expansive wave that is bringing consciousness back into the soils to once again produce intelligent food, to reset the mind and the souls of those who nourish themselves from these products and to empower our capacities, to reconnect. Becoming members of Impulso Biodinamico is done easily through its webpage (www.asociacionbiodinamica.mx). Please feel free to contact Impulso in order to promote a course, to become a biodynamic farmer through the possibility of having a consultant or even to get certified as a biodynamic farmer by Demeter International (learn more www.demeter.net).

The main goal is to achieve a unique Mexico, united in the transformation of human activities that impact nature — beginning with the understanding of agriculture as a human process, not 100% natural, learning how to act humanely with the soil and the animals, and thus with ourselves, in the way we feed ourselves, from how we produce what we eat, to how we can restore health and welfare in our relationships since we put our hands on the ground by working the field to create a positive impact, a virtuous cycle in all our relationships.

I see a possibility of a really promising future for the practice of Biodynamics in Mexico. Nowadays, perhaps because it’s trendy or because it seems that it might make it possible to recover something that is already considered lost, people are turning to new possibilities and field strategies. Our objective is that, for whatever reason, biodynamics can really become the new agriculture. The objective is to gradually permeate the fields, the soils and the minds of the farmers. If today it is necessary to start with biodynamic preparations and soil remedies, medicines for healing an ailing planet, before people are able to deepen in what is truly important, then that’s how we will do it. Eventually, the practice itself leads to the deepening and opening of minds and a path towards a truly resilient and restored Mexico.

Gaby Gonzalez is an architect by profession, an agriculturist at heart … Life has taken her on the path of self-learning, the reconstruction of her ideas, the way of thinking and the constant perspective adjustment. She is a proactive and enterprising woman who seeks the continuous improvement of her person and of her surroundings. She is dedicated to promoting regeneration projects in different areas: agriculture, bio-construction and health. She is co-founder of the new Mexican Biodynamic Agriculture Association, Impulso Biodinámico de México.