Since 2014, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been quietly subsidizing the German and French car manufacturing sector, through its asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP). To date, the ECB has purchased more than 10bn euros of securitized assets issued by Volkswagen, Renault, BMW and other leading companies in the sector.

Since 2017, Positive Money Europe has been vocally criticizing the way in which the ECB’s corporate quantitative easing programme (CSPP) benefits mainly massive multinational corporations, and in particular those contributing most to climate change. As our recent research has shown, we estimate that the ECB has invested more than 110 billions into carbon intensive industries.

Unfortunately, there is even more the ECB is doing in favour of these high-pollution industries. As early as 2014, the ECB had already launched the “Asset-Backed Security Purchase Program” (ABSPP), a premature version of quantitative easing which is focusing on purchasing securitized assets. In 2018 the ECB cumulative gross purchases of asset-backed securities reached 51.8 billion euros under the ABSPP. But until recently, we did not have any clear indication of where these funds have gone, and who really benefits from this unconventional ECB support.

This is why Positive Money Europe filed a freedom of information request to the ECB in July 2017, in which we demanded that the ECB provide as much information on ABSPP and CBPP3 as they do for the CSPP (which is only available due to external pressure exerted from the European Parliament). Concerningly, the ECB has rejected our request at the time, indicating that the full details of these programmes could be controversial if publicized.

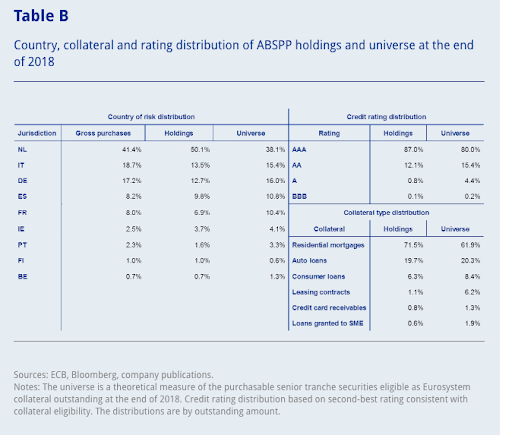

In March 2019, after the European Parliament supported our demand for more transparency on ABSPP, the ECB finally released an article in its Economic bulletin, which provides the aggregated data of the Asset Backed Securities Purchase Program (ABSPP). Although the information is incomplete, it nevertheless gives us a clearer picture of what the ECB has been purchasing (see Table B below).

Two main sectors benefit from ABSPP: housing and auto

The data revealed by the ECB confirms our fears: there’s more financial support backing high-pollution activities. In fact, 36.8 billion euros from the ABSPP programme have supported residential mortgages, while and another 10.1 billion have been invested in auto loans, accounting respectively for 71.5% and 19.7% of the entire programme. Both sectors are important contributors to global warming. Here again, on behalf on a biased ideology, the ECB remains blind to the environmental outcomes of its activities.

The ABSPP has been implemented in order to “help banks to provide credit to the real economy” and to “diversify funding sources and stimulated the issuance of new securities”, claims the ECB website. In this letter addressed to Positive Money Europe, the ECB explains further that “these programmes are aimed at encouraging market participants to invest in a category of assets.”

Residential Mortgage (RMBS) and Auto Loans are the main categories of the european ABS market. They are the so called “universe” of the ECB. Since the ECB is attempting to take a “market neutral” approach to selecting assets for purchase by the APP, it is therefore unsurprising that the residential and the auto sectors are benefiting the most from this 51.6 billion euros’ purchase programme.

Of course, a more granular analysis (which is not possible with the data not provided by the ECB) would be necessary to provide a comprehensive climate assessment of the programme. Nevertheless, a quick look at the structure of the two main sectors benefiting from the ABSPP allow us to conclude that the environmental footprint of the ECB activities is negative overall.

Rewarding pollution

The information disclosed by the ECB does not allow us to undertake a precise analysis of the environmental impact of the ABSPP. However, there is evidence from the housing and auto markets that those sectors are performing badly in an environmental context.

Turning to the housing sector, the urgent challenge is the building or renovating of energy efficient houses in order to reduce energy use – and thereby greenhouse gas emissions. The Residential sector “accounts for 40% of the energy use within the EU” according to the Buildings Performance Institute Europe, “97% of the building stock [in the EU] must be upgraded to achieve the 2050 decarbonisation vision”.

There are initiatives in Europe trying to create “green” RMBS. The EuroPACE programme, in particular, is aiming at aligning credit provision to energy efficiency goals. However, we doubt the ECB is expressively targeting those bonds in its purchases.

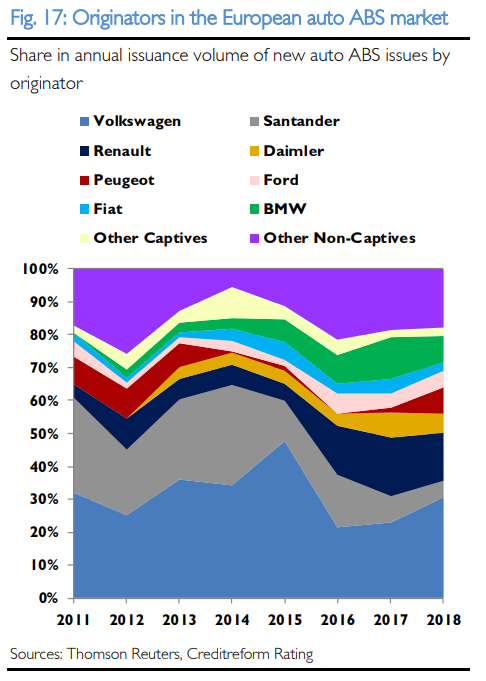

The climate output of the auto ABS is easier to estimate. As one would expect, the main providers of ABS in the auto sector are the big car manufacturers. In 2018, the first originator in the European auto ABS market was Volkswagen (30.4% of the market), followed by Renault and BMW – who are, we can legitimately assume, the main beneficiaries of the auto loan part of the ABSPP.

(This figure and the data about the european ABS market are taken from Creditreform’s annual rating report 2019).

Back in 2015, Volkswagen were accused of violating environmental regulations by falsifying the data produced by the cars’ pollution measurement devices. On top of that, the European Environment Agency (EEA) is ranking Volkswagen as one of the worst performers regarding the EU regulation on annual CO² gram per kilometer’ goals reduction. Renault, which is one of the good performers according to the same EEA’s 2017 report and second issuers of ABS in Europe, is however alleged by French regulators to have cheated in much the same way as Volkswagen.

The majority of the auto ABS seems to be performing badly regarding climate change. This should come as no surprise: according to the European Commission, cars “are responsible for around 12% of total EU CO2 emissions”.

The current dynamic of the residential and the auto sector is going in the wrong way regarding EU’s climate objectives. By adopting a “neutral” attitude towards the current market structure, the ECB is de facto amplifying this trend.

Time to move on

The concerns raised by the ABSPP revive issues laid in the CSPP: the ECB is investing mainly in carbon intensive sectors because it follows a blunt market neutrality approach.

The core problem is that the ECB’s philosophy is to select assets to purchased relative to their share within the market, and the ABS European markets are composed primarily of assets linked to carbon intensive activities – such as polluting car manufacturers or energy-inefficient houses.

Positive Money Europe stands for making sure the ECB uses the power of quantitative easing in a way that supports the type of society the EU wants. Unless one thinks cars are the future of our mobility, the current composition of ABSPP is hardly justifiable.

Quantitative easing should be more equitably targeted and used when appropriate conditions are met for environmental impact. A first good step for the ABSPP could be to specifically target car manufacturers that perform well in regard to EU environmental regulation, or to support residential loans which are linked to energy efficiency objectives (such as the EuroPACE program). Another solution could be to support more effectively ABS loans targeted to SMEs. At the moment, ABS loans to SMEs only account to a tiny 0.6% of the programme.

In comparison to the gigantic size of quantitative easing, the ABSPP is relatively small. It could therefore be used as an opportunity for the ECB to experiment how to channel QE reinvestments towards green activities.

Gift-wrapped car feature image via Marco Verch/Flickr, Creative Commons 2.0 license.