“The place where God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger coincide.” —Frederick Buechner

What is ‘right livelihood’?

Traditional economists assume work is a disutility that people try to do as little of as possible. Right livelihood reframes work as something that is beautiful and valuable and comes from a shared desire to contribute meaningfully to the world.

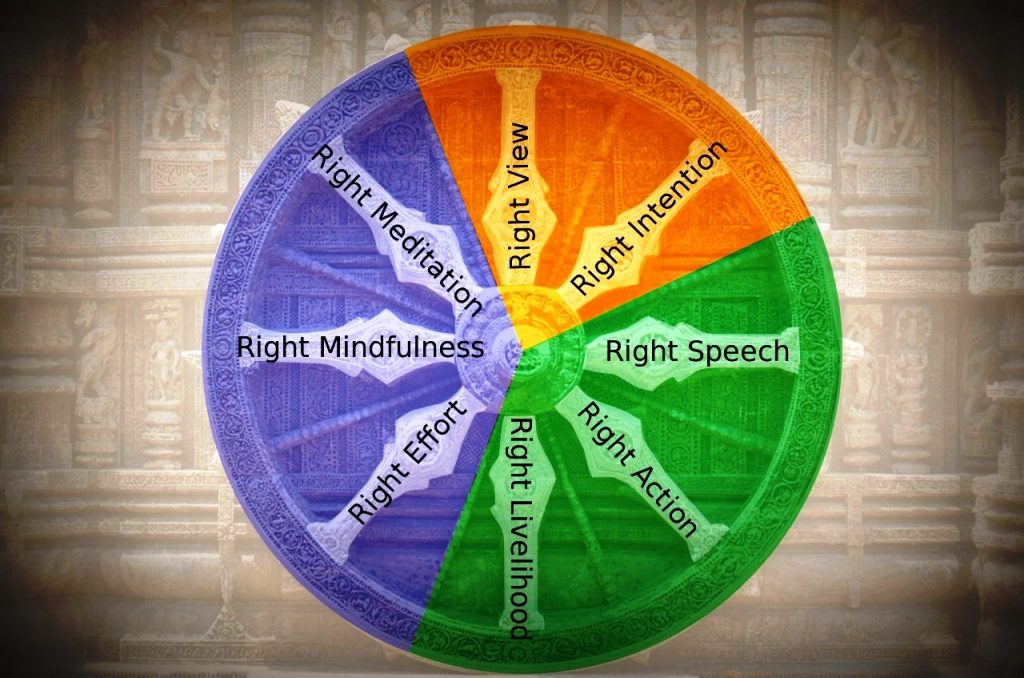

Right Livelihood has its origin in Buddhist philosophy and practice. It is the 5th mindfulness training that the Buddha shared in the eightfold noble path alongside right view, right intention, right speech,  right action, right effort, right concentration, and right mindfulness. Right livelihood reframes work as part of a spiritual path and discipline.

right action, right effort, right concentration, and right mindfulness. Right livelihood reframes work as part of a spiritual path and discipline.

The pursuit of Right Livelihood refers to the type of work we do, as well as our attitude towards work itself. In contrast to conventional professional development narratives around ‘climbing the corporate ladder’ or progress as making more money, right livelihood offers a view of work as a vehicle for self-actualization, systems change, and planetary healing. It invites the personal practice of approaching work with joy and intention and committing ourselves to efforts that support justice, equity, and ecological sustainability. Right Livelihood is our unique contribution to a more life-sustaining and enlivening world.

Right Livelihood: A Journey with No Destination

Thich Nhat Hanh says, “There is no way to happiness. Happiness is the way,” recognizing that there is no moment in time when we will have arrived at happiness. Rather, it is something we must cultivate in each moment. Similarly, we could say, “There is no way to right livelihood. Right livelihood is the way.” Right livelihood is not something we will eventually arrive at if we work hard enough or know the right people. It is not a fixed state, but instead, an ever-evolving journey of contribution  where the pursuit of meaningful work itself is the primary focus of our attention. It is a lifetime practice of making meaning through our work on a moment to moment basis, while also opening ourselves to a healthy relationship with personal goals and professional growth.

where the pursuit of meaningful work itself is the primary focus of our attention. It is a lifetime practice of making meaning through our work on a moment to moment basis, while also opening ourselves to a healthy relationship with personal goals and professional growth.

Right vs. Wrong: Finding Our Way

The pursuit of right livelihood also implies that it is possible to have a wrong livelihood. Traditionally, Buddhist teaching has identified this with the very worst of examples: weapons and chemical poison manufacturing, human trafficking, et cetera. The environmental activist and Right Livelihood Award winner Vandana Shiva says, more simply, “Right Livelihood is living in ways that actually contribute to harmony in nature and society. And the opposite, wrong livelihood, is to rupture nature and society.” In the modern context of corporate capitalism, wrong livelihood could be further expanded to include all work that contributes to systemic economic inequality and large scale ecosystem destruction through the exclusive pursuit of profit.

When framed as an individual journey, however, right livelihood is less about what is right or wrong at the moment and more about our own approach to work—on a daily basis and over the course of a lifetime. As such, it is possible to produce work from a place of joy and affection and contribute to the well-being of others in the workplace, all within an industry that systemically contributes to suffering and harm. Conversely, one can do work that meaningfully contributes to society while bringing stress, anger, and negativity into the workplace and creating a culture of toxicity for colleagues and patrons.

In walking the path of right livelihood, we are called to explore both the form and the content of our work: how we show up as compassionate humans in the workplace, as well as the actual output that we create through our labor. When we sense we are being unskillful or harmful in our attitude or actions, we can receive this as an opportunity for spiritual growth and the alleviation of suffering in ourselves and others. The most important practice on our right livelihood journey is how we respond in each moment and season of life.

What is the difference between right livelihood and a job?

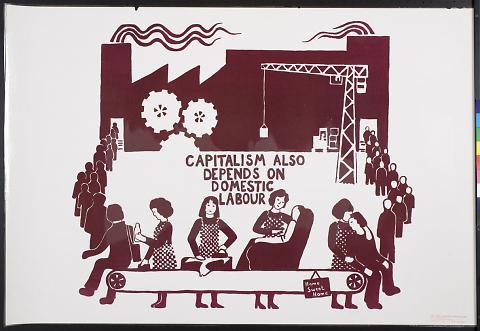

Right livelihood challenges assumptions about “work” and invites us to decouple productivity and income. It encompasses all efforts that contribute to a more life-sustaining and enlivening world,  including that which is paid and that which is unpaid. This means that work that is seen as “unproductive” or outside of the mainstream view of the economy such as caretaking, housekeeping, child rearing, art making, volunteering, and activism may actually be part of a right livelihood.

including that which is paid and that which is unpaid. This means that work that is seen as “unproductive” or outside of the mainstream view of the economy such as caretaking, housekeeping, child rearing, art making, volunteering, and activism may actually be part of a right livelihood.

The idea of right livelihood is similar to the perception of work within feminist economics, which posits that “reproductive labor” (caretaking, child rearing, and housekeeping) is a valuable part of the economy and deserves to be recognized as work even if it is often unmonetized, uncompensated, or under-compensated. This also implies that our right livelihood path does not begin with our first job and end with retirement, but instead, a child or teenager is cultivating her or his right livelihood through learning and participating in society, and a retired person can also contribute meaningfully to society through her or his efforts.

Reframing work according to right livelihood also invites us to perceive self-care as foundational. Capitalism enables a culture in which work is prioritized over personal health and community relationship. Alternatively, the idea of right livelihood invites us to see efforts to pursue physical and spiritual well-being as ‘productive’ because they enable our contribution and service to the world. Valuing exercise, spiritual practice, and self-care regimes helps to liberate our sense of self-worth from the dollar amount we are paid for.

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”—Audre Lorde, 1988

Connecting our work to larger movements for change

Perceiving right livelihood as our contribution to a more enlivening world invites us to explore how our vocations intersect with larger movements for social and ecological transformation. The transition to a renewable energy economy, for example, requires the productive effort of millions of people designing, constructing, and maintaining infrastructure that does not yet exist. Such a project unites literally all livelihoods related to the energy sector—from engineering and construction to marketing and finance—in the common cause of addressing an issue critical to Earth’s future.

Similarly, our livelihoods can also be vehicles for transforming the economic system itself, both in the way profit is shared and work is organized. The democratic ownership model behind worker cooperatives is increasingly recognized by activists and policymakers alike as a systemic solution to the economic inequality created by capitalism. Cooperative businesses, which exist in multiple forms throughout all sectors of the economy, distribute ownership and profits throughout a larger membership base (rather than concentrating it in the hands of a few owners) while also facilitating a culture of organizational democracy.

The cooperative model is not limited to business alone: worker self-directed non-profits, developed in part by the Sustainable Economies Law Center of Oakland, California, are emerging as important vehicles for workplace democracy in the non-profit sector. As a part of a larger movement to transform the way we work together, cooperative enterprises and worker self-directed non-profits are two models that can reposition democracy as a daily practice of inclusive and compassionate decision making.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are larger policy initiatives that would enable people to participate in more productive work not currently monetized, such as art making, care work, activism, and volunteering. This includes movements for universal healthcare, universal education, and a universal basic income. If we had a universal basic income, for example, we could even more so divorce our need to work for money to meet our needs and instead invite ourselves to find a right livelihood that isn’t required to pay bills.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are larger policy initiatives that would enable people to participate in more productive work not currently monetized, such as art making, care work, activism, and volunteering. This includes movements for universal healthcare, universal education, and a universal basic income. If we had a universal basic income, for example, we could even more so divorce our need to work for money to meet our needs and instead invite ourselves to find a right livelihood that isn’t required to pay bills.

Ultimately, aligning right livelihood with larger movements for change is an individuated process that will look different for everyone depending on the uniqueness of our own calling. Thinking systemically and strategically about how our work contributes to building a more beautiful world can provide it with depth of meaning and energy to sustain our spirit for the long haul.

Where do I start?

Recognizing that the pursuit of right livelihood is a lifetime journey with no final destination, we can begin by taking the time to look deeply into our own life, asking: where does my greatest hunger meet the world’s deepest need? How does this work contribute to larger efforts for social and ecological transformation? What is my greater potential for supporting a more life-sustaining and thriving world?

Maybe the connection is less obvious, or maybe your ‘work’ includes effort that the economic system does not value. If this is the case, open to the idea of an ‘economic base’ in a more mainstream context which allows you to build a longer-term livelihood aligned with your deepest passion. Do your own personal work, find creative ways to meet your needs, and cultivate peace with where you are in your life right now.

At the same time, the work to find right livelihood in our lives is not mutually exclusive with hustle, strategy, and the pursuit of lifetime personal and professional goals. The tools recommended by conventional career development approaches are all available for navigating decisions about how to make our living in a meaningful way. Conferences, networking events, and social capital are valuable assets in this journey. The practice is to find a healthy relationship with our growth and non-attachment to our goals, recognizing that these will not lead to happiness or fulfillment in and of themselves.

Right Livelihood and Global Transformation

Right livelihood is an opportunity to perceive work as a spiritual path of self-realization. By cultivating mindfulness, gratitude, and intention towards our effort in the world, we can continually align and improve our contributions to what Charles Eisenstein calls “the more beautiful world our hearts know is possible.” Finding meaning in our work is about listening deeply to what our hearts know is possible and bringing to life the beautiful truth inside all of us. By consciously aligning this authentic effort with unfolding currents of global transformation, we can find common cause in the intergenerational project of building a sustainable and equitable future on Earth.

Della’s talk on Right Livelihood for UC Santa Cruz