n 2014 Ursula K. Le Guin accepted the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters with a deliciously powerful speech:

Aware that her time was nearing its end, she declared that her “beautiful reward” was accepted on behalf of, and shared with…

. . . writers of the imagination who, for the last fifty years, watched the beautiful rewards go to the so-called realists.

I think hard times are coming, when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now. Who can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom—poets, visionaries; the realists of a larger reality.

. . . We live in capitalism; its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings.

Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art: the art of words. . . . The name of our beautiful reward is not profit. Its name is freedom.

Today, it is evident that those hard times have arrived for many, and will continue to arrive for ever more people around the world. As Simon Mont wrote in Tikkun’s recent issue on the New Economy, “capitalism is collapsing under the weight of itself, and it’s not pretty”.

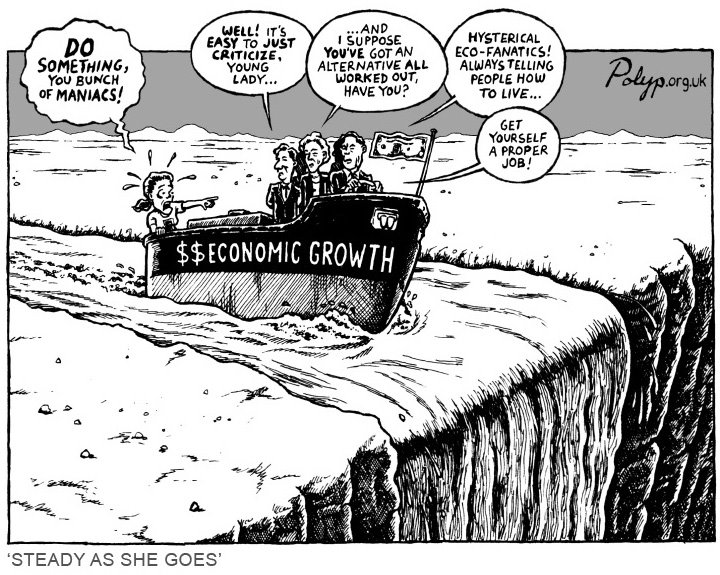

Our globalised world finds itself caught on the horns of a seemingly impossible dilemma – either cease growing, and so collapse the economy on which we all depend, or continue to grow until we overwhelm and destroy the ecosystems on which we all depend.

As my late mentor, the historian and economist David Fleming, put it,

It is certain that there are no simple answers to this—none that could be proposed without proposing at the same time a transformation in the whole of the way we think, work and order our lives.

It was in this context that I read that wonderful issue of Tikkun, exploring just such “alternatives to how we live now”. I found myself in wholehearted agreement with the pieces therein, but I could still hear that voice in the back of my mind – surely it’s not realistic. Despite the numerous inspiring examples cited, surely the mainstream economy is just too big, too established, too real, to be overthrown by such utopian dreams.

I’m certain I’m not the only one with this internal realist for company. But as the much-missed Le Guin said, the age of such realists is ending. Indeed, they have come close to dooming our world. For those paying attention, it could not be clearer that our time demands “realists of a larger reality”.

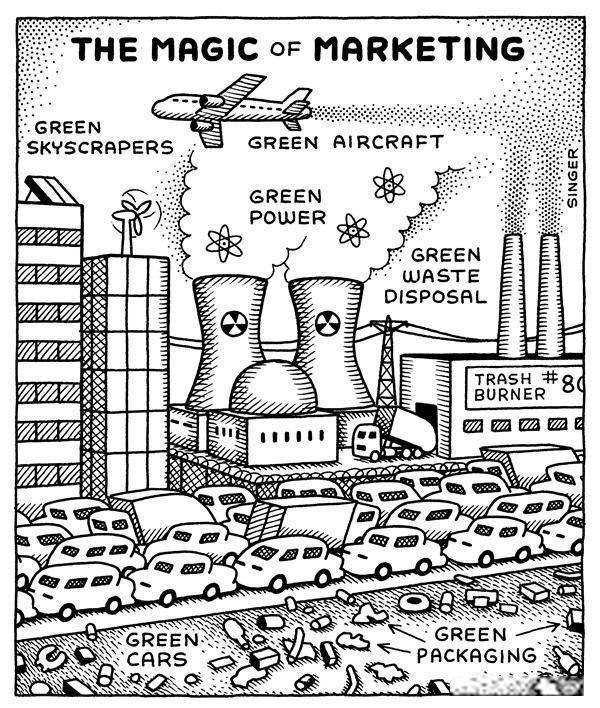

To take one pressing example, the inherently conservative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s recent Global Warming of 1.5ºC report makes it abundantly clear that the unfolding realities studied by climate science are dramatically outpacing the policies notionally intended to address them. They find that we must halve emissions in the next twelve years, and so their observations force them to call for:

Rapid and far-reaching … unprecedented transformation in the economy.

In other words, it has become impossible to be simultaneously realistic with regard to both the political climate and the physics of climate. The two stubbornly refuse to reconcile, so we are forced to decide which carries more weight, and then be profoundly unrealistic about the other.

To take present policy seriously demands a total rejection of the science. And to take science seriously demands a total rejection of present policy (with grassroots movements like the Extinction Rebellion and Climate Mobilization emerging accordingly).

As such, I turn to my internal realist with a challenge – which reality is it that deserves our allegiance: today’s political economy or physical reality?

Slightly to my surprise, he sees my point, and switches sides. And then, as an unrepentant realist, he gets straight to the point: What then does this larger reality demand? How might we solve the impossible dilemma?

What is necessary, that we might have a future?

“Patience”, I counsel my unexpected new ally. First, let us consider what we face.

An economy so violently contrary to our human instincts and desires that it leaves epidemics of depression, loneliness and suicide everywhere it goes. That uses mass media and financial stress to hollow our souls and seize control of both our days and our hearts, sparking not only economic and environmental devastation, but cultural and spiritual annihilation. Like villagers glancing fearfully up at the castle of some dauntingly powerful vampire, we live our lives under the shadow of the economy of undeath.

We owe this reality no allegiance. But we owe it respect. It is a worthy adversary, no doubt.

Yet its weak point is obvious. People straight up hate it. They hate their jobs and the materialist hollowness imposed on their lives. Nonetheless, as I grew up inside it the corporate media kept us blind to other possibilities, made it seem patently obvious – only common sense – that continuing to participate in this grim reality is the only realistic option.

But it’s a lie. And while a lie may take care of the present, it has no future.

The truth is that it takes immense energy (of all kinds) to keep a population suppressed – to fight all our contrary impulses; to quieten our profound inner misgivings, our spark of creativity and rebellion.

And this energy is running low. The domination economy of mass media and financial stress is probably the most effective system for alienating people from their spirit that our Earth has ever seen, but cracks are appearing everywhere. The edifice is crumbling. We all know, of course, that it is unsustainable – devouring its very foundations as it does – but it is somehow easy to forget that this means that it will end.

Easy to forget, perhaps, because for all that we resent the hollow emptiness it imparts, the prospect of its absence too is terrifying, for those of us who were only raised to secure water from a tap; food from a supermarket.

As Mont writes,

Only by knowing how to stay alive without the dominant system can we actually have the courage and wisdom to abandon or dismantle it.

He’s right, but it sounds pretty daunting. Must we then build a whole alternative economy before we can begin? Fortunately not…

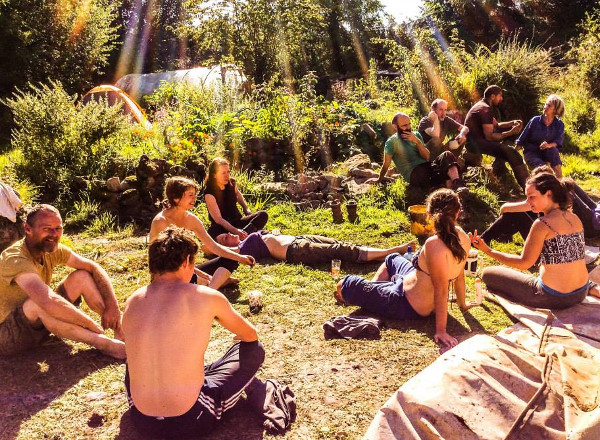

I am writing this article from my dear compañero Mark Boyle’s small community in Ireland, An Teach Saor (The Free House). It is a home from home for me, and one of many, many places around the world where the residents are making the logic of money and the market obsolete – abandoning it, before it abandons us. For example, the ‘free pub’ and bunkhouse here – The Happy Pig – is a place where anyone can stay, free of charge, and remember what it is to not have to find money simply to have a place to exist.

You may not have heard much about such places, because that suits the corporate media just fine. But awareness of their agenda brings an emboldening thought. Doubtless, for every bastion of hope and joy you hear of or encounter, there are a hundred more that you haven’t. It is a heartening multiplication that I regularly remind myself of; a counterweight to the mainstream media’s narrow, oppressive ‘realism’.

Here at An Teach Saor a different future is being built, day by day, smile by smile. One that is grounded in relationships of love and respect, and ultimately in the only economic system that has ever truly worked – the system upon which all others have depended – Nature.

Being here is a healing, nourishing experience, surrounded by inspiring books, wild nature and wonderful, trustworthy people with hands dirty from the soil, who seek nothing more from each other than the pleasure of companionship. Once we remember the taste of freedom, the zombie economy holds little allure.

Yet Mark’s words take me back to the wider world…

Despite knowing little or nothing of the bloody, mucky realities of land-based lives, techno-utopians will warn you to be careful not to romanticise the past.

On this, I agree, and I know it first-hand.

But be even more careful of those who romanticise the future.

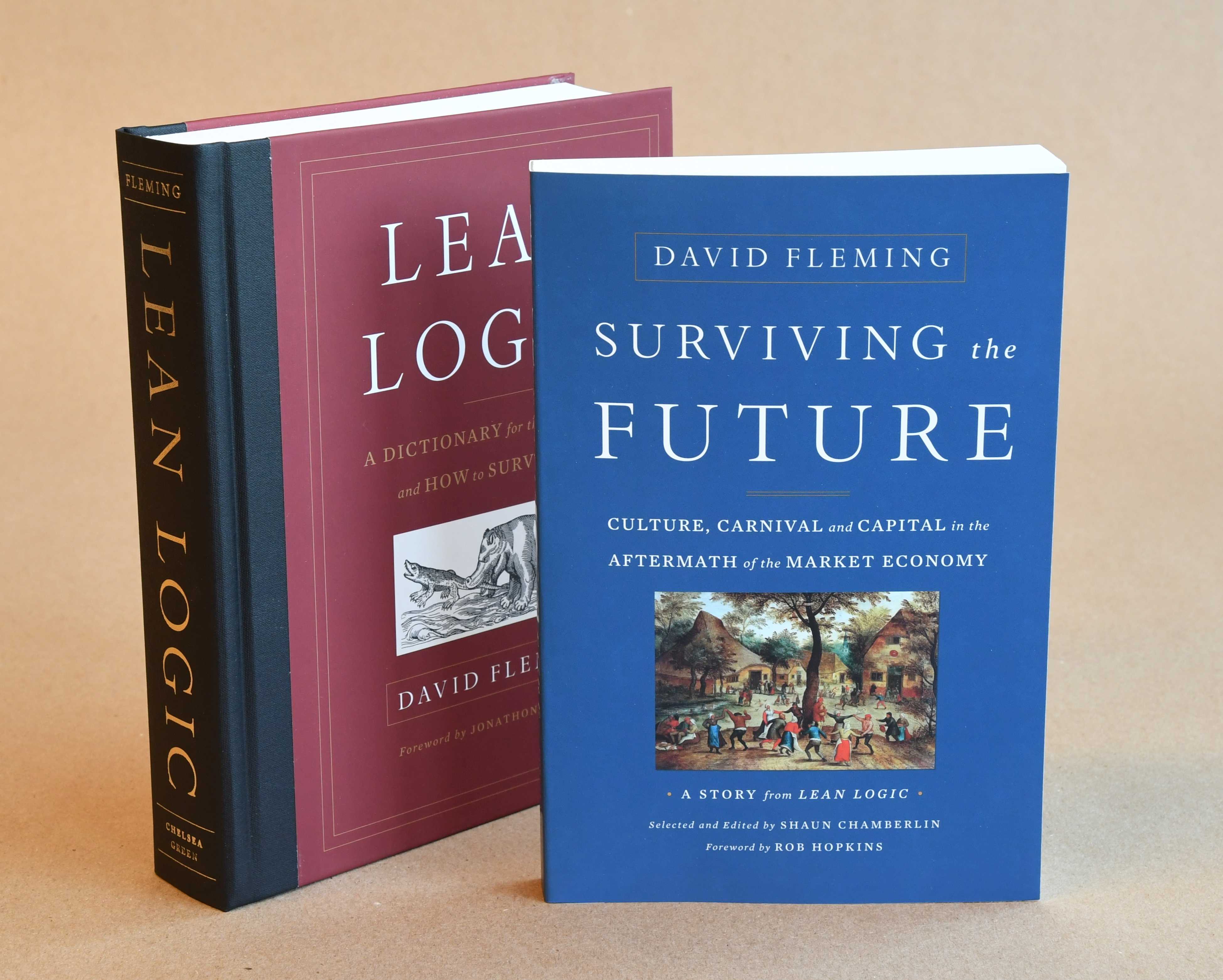

And among the books on the shelf here rests one that speaks to that very theme – Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy, a posthumously published work by my aforementioned mentor David Fleming.

Therein, he reminds us of just how unusual today’s ‘ordinary’ is, and how profoundly unrealistic it is to pin our hopes on market capitalism – an economic system that has existed for less than 1% of human history and is already not only destroying its own foundations, but those of life on Earth. In his words,

The Great Transformation has already happened. It was the revolution in politics, economics and society that came with the market economy, and which hit its stride in Britain in the late eighteenth century.

Most of human history had been bred, fed and watered by another sort of economy, but the market has replaced, as far as possible, the social capital of reciprocal obligation, loyalties, authority structures, culture and traditions with exchange, price and the impersonal principles of economics.

This historical context is critical. The New Economy our times call for is in many ways the Old Economy.

We are rediscovering the ways human beings related to each other for hundreds of thousands of years before we were ripped into isolation by the brief historical anomaly of market capitalism, into which most of us alive today happened to be born. Suddenly it makes sense that living as we do here should feel so right. After all, what is the Happy Pig – which sounds so radical to modern ears – if not a simple rekindling of the ancient Irish tradition of hospitality? As Mont put it:

[The New Economy] is a groundswell to relying on a memory harboured in our hearts to make real a vision of humans returning to deep relationships with earth, spirit, and each other, that is constantly evolving and changing, while staying acutely cognizant of the fact that we must relearn how to keep ourselves alive without capitalism and extraction.

Fleming took that dear memory harboured in our hearts and wrote it large across the page. “We know what we need to do,” he writes, “We need to build the sequel, to draw on inspiration which has lain dormant, like the seed beneath the snow.”

An Teach Saor is just one of thousands of communities around the world today inspired by his sparkling, tantalising writing, which also helped inspire the birth of the now-global Transition Towns movement. Why? Because his fundamental answer to our core dilemma is so refreshing – unique, perhaps, among modern economists. For him, the key to a better future lies not in jobs, growth and mathematics, but in culture, community and conviviality.

He notes, for example, the startlingly extensive holidays of the medieval calendar (five months of each year, in some places) and ponders why the good folk of the Middle Ages were enjoying so much more leisure time than we are in our technologically-advanced society. What gives? He explains,

In a competitive market economy a large amount of roughly equally-shared leisure time – say, a three-day working week, or less – is hard to sustain, because any individuals who decide to instead work a full week can produce for a lower price (by working longer hours than the competition they can produce a greater quantity of goods and services, and thus earn the same wage by selling each one more cheaply).

These more competitive people would then be fully employed, and would put the more leisurely out of business completely. This is what puts the grim into reality.

So in an economy like ours, a technological advance that doubles the amount of useful work a person can do in a day becomes a problem rather than a benefit. It tends to put half the workers out of work, turning them into a potential drain on the state (or simply leaving them destitute).

Of course, in theory all the workers could just work half-time and still produce all that is needed, as is promised by today’s latest wave of automation utopians. But in practice workers are often afraid of having their pay cut, or losing their jobs to a stranger who is willing to work longer hours. In the absence of a sense of community or mutual trust, and having been taught to seek their security in a wage, people instead compete against each other for the right to perform the pointless tasks that anthropologist David Graeber memorably characterised as “bullshit jobs”.

Meanwhile, governments see that the only way to keep unemployment from rising to the point where the system breaks down is through endless economic growth, which thus becomes a non-negotiable obligation – a dogma. So we just keep growing and cross our fingers that somehow Nature will continue to bail us out forever. As Fleming put it,

Civilisations self-destruct anyway, but it is reasonable to ask whether they have done so before with such enthusiasm, in obedience to such an acutely absurd superstition, while claiming with such insistence that they were beyond being seduced by the irrational promises of religion.

Take heart though, for when the current paradigm transparently offers nothing but a literal dead end, we can be sure that we are on the cusp of a fundamental shift.

And Fleming provides the radical but historically-proven alternative: focusing neither on the growth nor de-growth of the market economy, but on huge expansion of the ‘informal’ or non-monetary economy—the ‘core economy’ that keeps our society alive, even today.

This is the economy of what we love: of the things we naturally do when not otherwise compelled, of music, play, family, volunteering, activism, friendship and home. Yet over the past couple of centuries, this core economy has been much weakened, as the ever-growing stresses of precarious employment, debt and rising prices have left people with less time and energy for friendships, family and fun.

As such, to sustain a post-growth economy we will need to get beyond mainstream economics’ aim of minimising spare labour. This ‘spare labour’ is what most of us might call spare time—time enjoyed outside the formal economy—a welcome part of a life well lived rather than a ‘problem of unemployment.’

Those extensive holidays of former times were far from a product of laziness. Rather they were, in an important sense, what men and women lived for. ‘Spare time’ spent in feasting, performing, collaborating and merrymaking together formed the basis of communal bonding, membership and trust.

These shared cultural ties then bind people together in cooperation, support and solidarity, the essential foundations for the communities which have thrived throughout history in the absence of economic growth (and its attendant certainty of devastating collapse) or full-time employment. As Fleming writes,

The [future] economy will depend for its existence on a deep foundation in culture. It is possible to live without it, but only for a time, like holding your breath under water.

Or as one of his readers put it – when productivity improves, “in our system you have a problem; in Fleming’s system you have a party.”

This is the party we are enjoying here at An Teach Saor, and in so many other places, families and communities around the world. Meanwhile, Fleming’s writing up on the shelf, with its rare combination of charm and rigour, reminds us that nurturing the core economy back to health in this way is not merely some quaint and obsolete shared longing, but an absolute practical priority – unadulterated realism.

Wherever we are, we can spend our days relearning how to seek our security in each other – and in Nature – rather than in money, and as we do, we notice that the unfolding end of the undeath economy (no longer our undeath economy) becomes less something to fear, and more something to celebrate.

We think less about what we might stand to lose and far more about the joys we had already lost and are slowly learning to regain, together. At long last we are remembering how to build a world in which, as dear David wrote,

There will be time for music.

—

Note: I first drafted this in September, but then decided to rework parts of it for publication as free-standing articles for Tikkun and Kosmos magazines.

With those pieces now published, I have decided to release the original full piece here.