Just as four big oil and gas producers block the UN climate policymaking conference in Katowice, Poland from welcoming a report on the science of the 1.5 degree Celsius (°C) target which it had commissioned three years earlier in Paris, new evidence has emerged of the striking contradiction between word and deed at the 24th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP24).

In a deadly diplomatic strike, big fossil fuel nations took a key scientific report out of the Katowice text, replacing acknowledgement of the report’s compelling case for accelerated action, with a more ambiguous formulation which merely notes the report’s existence.

Objections from Saudi Arabia, the US, Kuwait and Russia to wording to “welcome” the 1.5°C report was enough to sideline it, with Saudi Arabia threatening to disrupt the last stretch of negotiations between ministers this week if the word “welcome” was not replaced by “note”.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 1.5°C report states in plain language that averting a climate crisis will require a wholesale reinvention of the global economy. By 2040, the report predicts, there could be global food shortages, the inundation of coastal cities and a refugee crisis unlike the world has ever seen. A number of scientists contend that the report wasn’t strong enough and that it downplayed the full extent of the real threat. They say it doesn’t account for all of the warming that has already occurred and that it downplays the economic costs of severe storms and displacement of people through drought and deadly heat waves.

As COP24 sits down to write a rule book governing the implementation of the Paris Agreement, the chasm between goals and committed actions is growing alarmingly wide. Whilst the Paris goal is to hold the increase in the global average temperature “to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”, the current commitments would result in warming of 3.3°C, according to ClimateInteractive. When climate-cycle feedbacks are taken into account, warming would likely be in the range of 4–5°C, which is considered incompatible with the maintenance of human civilisation.

World Meteorological Organisation Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said on 4 December that if current trends continue, temperatures may increase by 3-5°C by the end of the century.

Two new research projects underline the Katowice dilemma.

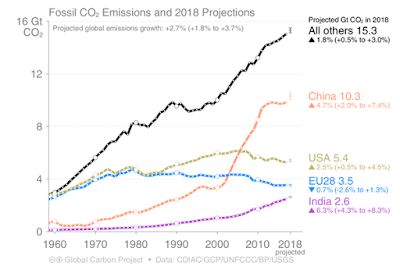

The first, and widely reported, are estimates from the Global Carbon Project, of human-caused carbon dioxide emissions (CO2) in 2018, which shows they will likely hit a new all-time high of 37.1±2 billion tonnes of CO2, 2.7% higher than 2017. Whilst emissions in the EU are likely to be lower by 0.7%, there are projected increases from the two biggest polluters — China up 4.7% and the US up 2.5% — as well as a 6.3% increase in India (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1: Emissions and projections for 2018 by country |

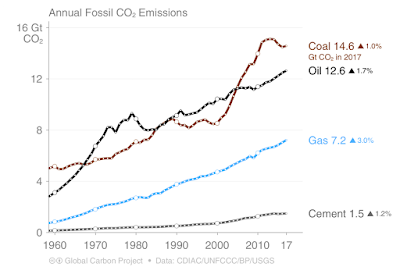

This is driven by a 3% increase in gas emissions, and a 1.7% increase from oil. And coal, after falling for the three previous years, is projected to be up by 1% (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2: Emissions and projections for 2018 by fuel type |

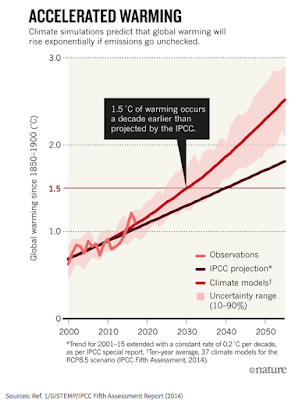

The second piece or research, which has received scant attention, is an analysis of why global warming will accelerate much quicker than the projections of the IPCC. In a comment published in Nature on 5 December, Yangyang Xu, Veerabhadran Ramanathan and David G. Victor say that the 1.5°C global warming threshold will occur around a decade earlier than projected by the IPCC, around 2030, with Earth hitting 2°C by mid-2040s (Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3 |

This accelerated warming was discussed by RenewEconomy in April this year, as 1.5°C of warming is closer than we imagine, just a decade away.

Xu and his colleagues say warming is likely to increase to 0.25-0.32°C per decade, driven by rising emissions, declining air pollution (lower sulfate aerosol cooling) and the cycle of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation which will combine over the next 20 years to make climate change “faster and more furious than anticipated”. The problem with the IPCC projections is that they rely too heavily on longer-term modelling outcomes, and the “climate-modelling community has not grappled enough with the rapid changes that policymakers care most about, preferring to focus on longer-term trends and equilibria”.

On this, there is likely to be studied ignorance at Katowice. When big oil and gas producers block recognition of relevant science, how can the fact that 1.5°C is likely only a decade or so away enter the conversation when even the “best” scenarios on the table talk about emissions continuing to 2050, at which point the world will have also passed the 2°C threshold?