What do Keynesian Democrats think about the movement for post-growth and de-growth economics? Dean Baker, a senior economist at the Center for Economic Policy Research in Washington, DC, has given us some insight into this question. In a recent blog post, republished by Counterpunch, he takes aim at two articles that I wrote for Foreign Policy in which I argue that it is not feasible to reduce our emissions and resource use in line with planetary boundaries while at the same time pursuing exponential GDP growth.

Baker agrees — thankfully — that we need to dramatically reduce emissions and resource use to prevent ecological collapse. But he thinks that this is entirely compatible with continued GDP growth.

Let’s imagine, he says, that a new government imposes massive taxes on greenhouse gas emissions and resource extraction while at the same time increasing spending on clean technologies, with subsidies for electric vehicles and mass transit systems. Baker believes that this will shift patterns of consumption toward goods that are less emissions and resource intensive. People will spend their money on movies and plays, for example, or on gyms and nice restaurants and new computer software. So GDP will continue growing forever while emissions and resource use declines.

It sounds wonderful, doesn’t it? I, for one, would embrace such an outcome. After all, if growth was green, why would anyone have a problem with it? Baker makes the mistake of believing that degrowthers are focused on reducing GDP. We are not. Like him, we want to reduce material throughput. But we accept that doing so will probably mean that GDP will not continue to grow, and we argue that this needn’t be a catastrophe — on the contrary, it can be managed in a way that improves people’s well-being.

So who is right? Well, all of the empirical models that explore this question test precisely the policy tools that Baker suggests: taxes on bad stuff and subsidies for good stuff. And yet every single one of them comes to the same conclusion: even under the most aggressive policy conditions, resource use still rises, and emissions don’t fall fast enough. Why is this? Because the scale effect of growth — which is exponential, remember — outstrips the pace of gains from efficiency improvements and new technology.

But Baker doesn’t bother to deal with any of this evidence. Maybe he didn’t read the underlying studies (links can be found here). If so, we need better than that from someone of Baker’s stature and influence.

Baker imagines an economy that is increasingly based on services. This sounds reasonable on the face of it. But services have grown dramatically in recent decades, as a proportion of world GDP — and yet global material use has not only continued to rise, but has accelerated, outstripping the rate of GDP growth. In other words, there has been no dematerialization of economic activity, despite a shift to services.

The same is true of high-income nations as a group — and this despite the increasing contribution that services make to GDP growth in these economies. Indeed, while high-income nations have the highest share of services in terms of contribution to GDP, they also have the highest rates of resource consumption per capita. By far.

Why is this? Partly because services require resource-intensive inputs (cinemas and gyms are hardly made out of air). And partly also because the income acquired from the service sector is used to purchase resource-intensive consumer goods (you might get your income from working in a cinema, but you use it to buy TVs and cars and beef).

Of course, with the taxes and subsidies that Baker envisions, perhaps this trajectory would look different. But existing evidence is clear that it won’t look different enough.

Think about it. Even if we do manage to slim down gyms and cinemas so that they are powered by the sun and are extremely resource-lite — as lite as they can possibly be — as we continue to grow those industries exponentially then resource use will quickly start rising again. That’s what scholars have discovered over and over: that once you reach the limits of resource efficiency, growth drives resource use back up.

But let’s say that we put a hard cap on resource use, so that this effect can’t happen. Will growth still occur?

Maybe. But if so, let’s not pretend it would be pretty. We need to be cognizant of how capitalism works. For two hundred years, capitalism has depended on extraction from nature and human bodies. It has always needed an “outside,” external to itself, from which it can plunder some kind of original value, for free, without an equivalent return. That’s what fuels growth. So what happens when capital is no longer allowed to plunder nature? Where will it turn to next, in its hunger for growth? What new forms of exploitation will it devise?

Ultimately, Baker admits that he’s agnostic about the relationship between growth and ecology. He says he is open to the possibility that tight restrictions on emissions and resource use might contract the economy. But he argues that even if this is true, we shouldn’t advertise this fact by saying that we are against growth, because we might scare people away and lose political support.

I understand where he’s coming from. But while it may seem politically sensible, there are a number of problems with this approach.

First, if the economy does end up contracting, it will be an absolute disaster unless we are prepared for it. An economy that is designed to need growth will collapse when it doesn’t get it. Firms will go bust, people will lose their jobs, families will be evicted from their homes. Whatever party is in power during this chaos will quickly be toppled.

By contrast, because degrowthers are liberated from the illusion that growth will carry on forever, we openly call for an economy that does not require growth. We call for policies like a shorter working week, a job guarantee, debt-free currency, fairer wages, progressive taxation, universal social services, and so on, so that we can scale down economic activity in a stable manner, while at the same time facilitating human flourishing.

Second, if we run headlong into economic contraction unprepared, then the reaction from corporations and politicians will be to do whatever it takes to get growth going again, even if it means slashing the very regulations that Baker puts so much faith in. In a growth-at-all-costs economy, those measures will be extremely vulnerable — the first to go. In a recent report, economist Tim Jackson argues that this is exactly what’s happening in high-income countries that are facing secular stagnation. Desperate for more growth, they’ve gone about shredding what few regulations remain.

Third, there is nothing to be gained by deceiving people into believing that green growth is possible and that the status quo can continue forever when there is no evidence for this. If this imaginary future fails to materialize, people will feel profoundly betrayed.

Imagine that, during the run-up to World War II, the US government had told people that everything was going to carry on as normal. There would have been riots at the first sign of fuel rationing — as we’re seeing right now with the Gilets Jaunes movement against the fuel tax in France. A much better strategy is to get people on board with the transition right from the beginning, with a coherent, integrated economic framework and a compelling alternative narrative.

Finally, and most importantly, the strict measures on emissions and resource use that Baker hopes for are difficult to get in the first place precisely because people are focused on growth. Economists and politicians realize that such measures will entail a trade-off with growth, which is why they resist them so aggressively (William Nordhaus’s arguments are the most obvious example of this). If we shift to an economy that’s not focused on growth, Baker’s strict measures will be much easier to pass. This is strategically important, because we don’t have time to wait around for growthers to agree to high taxes on carbon and resource use — it will never happen.

Baker’s main concern seems to be that people will be afraid of a post-growth narrative. But he doesn’t bother to cite any evidence for this. If he did, he would find that the exact opposite is true. A striking new poll by Yale shows that 70 percent of Americans believe that environmental protection is more important than growth — and this is true even in deep red states. Another poll finds that 70 percent of people across middle and high-income nations believe that overconsumption is putting our planet and society at risk. Similar majorities also believe that we should strive to buy and own less, and that doing so would not compromise our well-being.

People realize that our growth-addicted economy is driving us into disaster, and they are eager for an alternative. Whatever political movement can speak truthfully to that deep-felt concern and offer real hope — not just green-growth fantasies — will be able to command incredible popular support.

Interestingly, Baker himself accepts that continuous growth is not necessary to improve people’s lives in high-income countries. He recognizes that we can do this right now, without any growth at all, simply by redistributing the abundance that we already have. So if that’s the case, then why continue clinging to the growth fetish? Baker offers no positive defense of growth. He just takes it for granted as given.

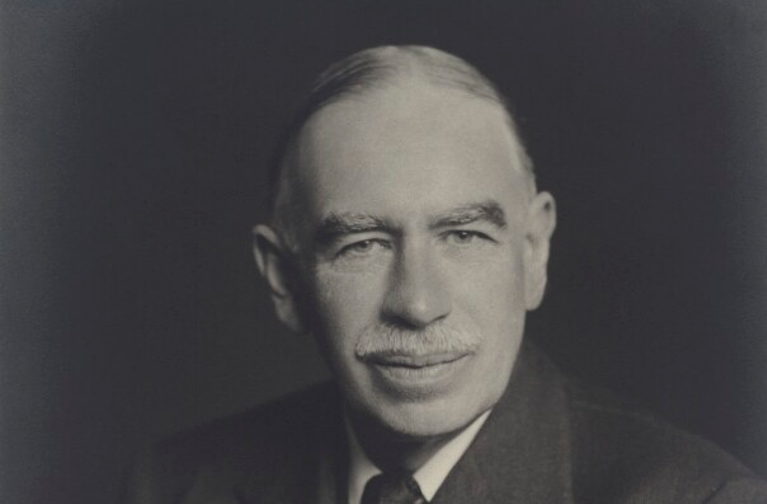

As a longtime Keynesian, maybe Baker has bought the narrative that Keynes himself saw growth as a necessary feature of the economy. If so, he is mistaken. Keynes was not obsessed with growth, but with stability. He wanted to raise the level of economic output, yes, but only for a specific defined purpose; he never thought that growth should continue forever. This is a perverse idea that Keynes himself never held.

Ultimately, what Keynes wanted was stability. And this is why we need Keynes now more than ever: not in order to justify eternal growth, but in order to achieve stability in the absence of growth, and while actively scaling down the most destructive sectors of our economy. If the Keynesian Left hopes to contribute anything to our battle against ecological breakdown, a post-growth narrative is going to have to be part of it. Let’s hope that Baker will help articulate such a vision.