The monetary system we have is a fundamental cause of our problems, and setting up new systems is crucial in the development of alternative economies. However some popular initiatives are sadly mistaken and can have few if any beneficial effects. The goal must be to set up a system that enables previously idle people and resources to begin producing necessities for the locality. This is easily done.

First, let’s look at the main faults in the present system.

The present monetary system … works for the rich.

Money is puzzling stuff. It should just be little more than something that facilitates economic exchange, the safe keeping of savings, and the keeping of accounts. But in our system it is also a commodity, something that can be “hired” for a fee, i.e., borrowed and paid back with interest. Thus there is now a vast industry managing this lending, recently so big that it was making 40% of US profits. Kennedy (1995) estimated that 40% of what we pay for goods gets siphoned off into interest payments.

What’s wrong with the system? There are four major faults.

1. In a market system things go to those who are able and prepared to pay most for them. That explains most of what is wrong with the world. For instance there is enough food produced to feed everyone in the world but about one third of world grain is fed to animals in rich countries while at least 800 million are hungry all the time. Why? Simply because it is more profitable in the market to sell the grain to feedlot beef produces etc. In a market economy, need is irrelevant and ignored; the rich can take resources and goods because they can afford to pay more for them.

So it is no surprise that money is lent mostly to richer people, those able and willing to pay the highest interest rates the lenders can get. This means that most of a society’s capital goes into setting up industries that serve richer people, i.e., that produce goods they want. Hence there is no industry producing very small, cheap, humble but sufficient housing. Banks are not going to lend to a firm intending to produce housing poorer people can afford when they can lend to firms that are building McMansions and are able to pay much higher interest rates. So there are many socially desirable and indeed crucially necessary ventures that do not get set up because their proponents cannot pay the higher interest rates that are affordable by firms intending to produce non-necessities for higher income people.

This problem cannot be solved unless you do something to prevent the higher income consumers, investors and developers from being able to get all the capital that could be borrowed, i.e., unless you regulate access to capital somehow, which means interfering with the freedom of the rich to get whatever they want by being able to pay more for it. This can be done by setting certain sources of capital aside to be lent to particular groups under particular conditions, such as obliging banks to allocate a certain percentage of their lending for low income housing, at rates that are capped (…which was once the rule in Australian.) But in the era of neoliberal triumph governments refuse to do this kind of thing, because capitalist ideology has convinced everyone that it’s best to leave as much as possible to be determined by the freedom of market forces.

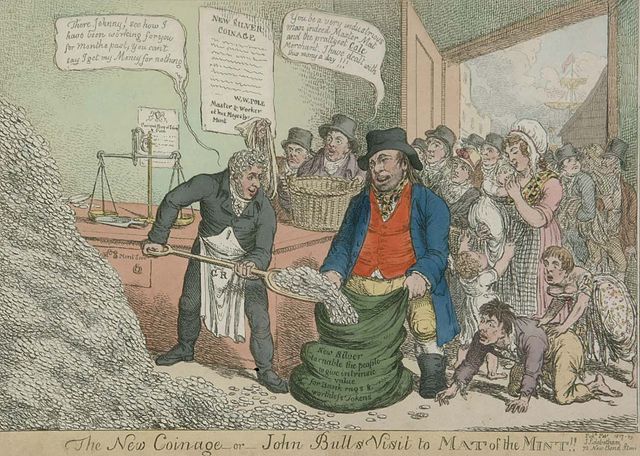

2. The power to decide what money is used for is in the hands of the few who have most of it, that is, the rich and the banks. They are the ones who decide what ventures money will be lent to. For example the Duke of Wellington was heading to lose the Battle of Waterloo until the Rothschilds decided to lend to him. Thus … “The Rothschilds had decided the outcome of the Napoleonic Wars by putting their financial weight behind Britain.” (Grecco, 2009, p. 91.) This means the rich have the power to put the world’s resources, our resources, into what further enriches them, not into what people need. So if we are to develop the things our community most urgently needs we will have to get around the power of capital owners to lend to and develop only whatever will maximise their wealth.

3. The mass of ordinary little people are prevented from setting up the many little firms they could be operating to produce for their communities many of the things they need. Because access to finance is decided by ”market forces” billions of people are forced into idleness and deprivation because they cannot get the small amounts of capital they need to establish little farms and workshops. Further, the land and resources they could be using are taken (bought) by the rich and put into ventures that are most profitable in the global market system. Land that could be supporting many little farms producing for local use is taken by agribusiness corporations to grow crops for export. Your town might desperately need a youth club or meeting place for the elderly but what you are more likely to get is a fashionable boutique or a mega-supermarket. Walmart sets up, undercuts local prices and ruins all the local firms, and ends up taking all the business and opportunities to earn, and eliminating livelihoods. The local resources of land, labour, talent flow into Walmart’s activities, or remain idle, and are not put into providing for local people (apart from the few low paid jobs created.)

A major consequence is the appalling theft that is the conventional approach to Third World “development.” The taken for granted doctrine asserts that what is developed must be determined by what those with capital decide to develop, i.e., what they think will maximize their global profits. Guatemalans don’t really need cosmetics factories or cut flower export plantations, but that’s irrelevant… investors aren’t going to make good profits growing beans for hungry Guatemalan peasants are they? So perhaps 4 billion people round the world remain very poor and unable to produce much while they are surrounded by land, forests, fisheries, mines, dams, power stations, ports, factories and infrastructures that send out wealth to rich world supermarkets and investors. Thus conventional “development” is best regarded as a form of legitimized plunder. The possibility that all that productive capacity could be being harnessed by local people to producing things that could be directly and immediately meeting their own basic needs is far too complicated for the highly trained conventional economic mind to comprehend.

Liberation from all this for a town or a nation must involve the capacity to create our own currency …but the IMF prevents nations indebted to it from doing this. They are forced to borrow from the big banks, at high interest rates, and therefore forced to cut welfare and other spending and to sell assets cheaply to pay off the debt. So lots of Greeks must suffer poverty when the Greek government could be enabling them to produce necessities, if it was able free to issue a currency designed for this purpose.

4. The conventional financial system is extremely unstable, fragile and dangerous and periodically self-destructs causing immense damage. It inevitably booms and then busts. From time to time it implodes destroying the lives of millions. In the GFC [Global Financial Crisis], 10 million Americans lost their homes. This is because the system is driven by greedy people with money who constantly chase after the most profitable investments they can find. They can’t make good profits these days investing in the production of useful things like more fridges or bicycles (the wages of American workers who might like to buy them have not risen significantly in 40 years) so they speculate buying assets etc. For instance they buy houses hoping they can soon sell them at the higher price generated by their speculation. Financial institutions thrive on this, lots of fees, and lots of loans banks can make to the speculators. But before long the bubble bursts, the lenders fear their loans will not be repaid so they suddenly try to claw them back, bankrupting borrowers, and they stop lending, i.e., cut the access to credit firms need. Large numbers of little businesses are busted and people lose their homes and jobs.

GFC1 was nothing like the catastrophe GFC2 will be. Global debt, i.e., the amount borrowed mostly for speculative purposes, is now $325 trillion, much more than three times global GDP and far higher than it was before GFC1.

On all the above counts it is obvious that the system is marvelously well designed to benefit the rich, while depriving the rest of us of the goods, jobs and thriving communities we could have if we could get the relatively small amounts of capital that would be needed to establish businesses that would meet needs. It is no surprise that the solution to the GFC they tried was to print and give trillions of dollars to the rich, on the amusing assumption that this would stimulate investment and get the economy going again…when all it did was further enrich the rich and fail to get the economy going again. Duh. Just about the only country that did anything remotely sensible was Australia where the government quickly gave $900 to everyone, and we were just about the only country where the economy did not go down.

One cannot exaggerate the stupidity of an economic system driven by these principles and mechanisms. There are plenty of resources around – land, water, timber, skill – to provide good lifestyles for all, but billions of people remain deprived while astronomical volumes of capital are shoveled into speculating by very rich people who are only interested in becoming richer. As I write, worries are building about a stock market crash, which would cause widespread damage to firms, towns and little people. It is taken for granted that this has to be accepted as a natural phenomenon, like a storm or a flood, when it is no more than a consequence of the kind of financial system we have.

By the way, note the sanctity of interest, the fact that its moral significance is never questioned. In a world where most people have to work hard for their incomes, and large numbers cannot even get work, no one sees any problem with some being able to get incomes without having to do any work at all, because their income comes as interest on their investments … while they consume food and goods produced by those who do have to work. In a satisfactory economy no one would get an income without working for it. There are plenty of ways of accumulating “capital” for socially desirable investments without helping those who are rich to get richer.

As noted above, years ago Kennedy (1995) estimated that maybe 40% of the price we pay for goods goes into paying interest. The financial industry is the interest-getting industry, and recently was making 40% of US profits.

There is another very important reason why interest must be abandoned in a sustainable society. It is incompatible with a zero-growth economy. If a certain amount of money is borrowed this year, then if it must be paid back plus interest then where is the excess to come from? Borrowers can only pay that interest if during the year they have produced and sold goods of a value greater than the sum borrowed…meaning that they must have grown the economy … which is not compatible with a sustainable world.

It is not difficult to see how the basics of a satisfactory monetary system could quickly and easily be implement … but governments will not do this because that would be to go heavily “socialist”. To take control of money away from the rich and their banks would be (correctly) regarded as “interfering with market forces”. It would be to devastate the flows of wealth to the parasitic financial sector. It would therefore not be tolerated.

So we need to go around that irredeemable system to set up our own quite different monetary systems.

Alternatives.

Before discussing alternative monetary systems it is important to stress the context, the situation we will be in. In the short run, the next few decades, it will at best be grim. The present absurdly unsustainable and unjust consumer-capitalist society will be dying or dead. (If you want to check my reasons for this claim, have a look at TSW, 2018.) Globalisation and the obsession with growth and affluence will be over and in a world of severe scarcity your community’s focal concern will be how to collectively organize the local economy to provide as many basic necessities as possible from local resources, enabling all to have a high quality of life living simply.

The basic model for an alternative monetary system is the simple LETS arrangement [Local Exchange Trading System]. Imagine that Fred grows vegetables and Mary bakes bread but neither has any money so they can’t buy and sell to each other. So Fred just writes an IOU for $2, the price they agree for a loaf of bread, and gives it to Mary who gives him a loaf. Mary then buys from Fred the amount of vegetables they agree is worth $2, handing him the IOU as payment. They have enabled exchange by creating their own money. In a community using such IOUs everyone can keep track of whether they have bought more than they have sold to other members of the system. Groups of big corporations now use these systems for million dollar purchases between firms in the group.

A major virtue of LETS is that anyone and everyone can get/create money, that is, can trade, buy and sell. Money is not scarce. In the present system it is very scarce and therefore those who have it can charge a high price, interest, when they hire it out, i.e., lend. Note that the money Fred and Mary created does not involve interest.

But the big limitation with a LETS is that it doesn’t help much with the setting up of productive capacity, the establishment of firms to produce things to sell. Usually participants can’t buy much because there isn’t much they can produce to sell to earn the money/credit to pay for things. To set up even a mini business there is usually a need to get hold of “capital” of some sort. Firstly, this problem is minimized when the focus is on meeting basic needs in low tech and cooperative ways within a community concerned with sufficiency, simplicity and meeting basic needs, because not much capital is needed to establish simple garden and craft enterprises. In addition much of it can take a non-monetary form. For instance if an ecovillage wants to build simple premises for its beekeeper it might get all the timber, mud bricks, expertise and labour from within the community without having to pay money for any for it.

Secondly, where normal money is needed, for instance to pay for roofing iron and cement, it can be accumulated as small loans from people who will be repaid later by access to whatever the venture is going to produce. For example one US restaurant got the dollars to set up by printing meal vouchers and selling them … to people who could come in and spend them on a meal when the restaurant had opened. This strategy can be applied to much bigger things such as a town bakery that would produce necessities and employ people and enrich the town but can’t be built without buying materials from the national economy.

However the best option is for the town to set up its own “bank”. At its simplest this can be an account in a normal bank into which a few of us deposit some of our savings to form a pool of capital that our elected board of directors can lend to good causes, mostly tiny businesses that will employ locals and produce important things. In Maleny, Australia, some of the locals set up a town bank in two rooms in an old house, operating according to a charter of rules participants drew up and voted on. One rule was that loans would only be for good causes, and another was that none of the capital would be lent outside the town.

This is the basic “mutual” form, whereby a group of citizens contribute some of their savings to enable loans to each other, minimising overhead costs, and avoiding the paying of interest and dividends to shareholders. Ideally and eventually the council or the state government would set up operations like this, that is, establish public banks (…which outperform the private banks; see below on the Bank of North Dakota.)

Obviously these instances show that the money and its creation are not the central issues. In a LETS, the use of the newly created money is just an accounting device, whereby participants can exchange things among each other and keep track of what amount of credit and debt they have. What matters most is creating productive capacity, especially being able to set up operations that enable previously unemployed and poor people to start producing things they and other local people need.

Just about every neighbourhood and town has lots of productive capacity sitting idle, especially unemployed people (and time wasted in front of a screen) that could be producing necessities and providing livelihoods. The crucial question is how can money creation contribute to doing this?

Mistakes.

Unfortunately the most popular form of alternative currency doesn’t do it at all. This is the “substitution currency,” which is popular within the Transition Towns movement.

Substitution currencies are new notes printed by the town and purchased by people using old/national money to pay for them. The rationale is supposed to be that because the new money can only be spent within the town it gets people to buy local products. But anyone who understands the importance of buying locally will do so regardless of what currency they have, and anyone who doesn’t understand will buy what’s cheapest, which is typically an imported item. Obviously what matters here is getting people to understand why it’s important to buy local, and just issuing a local currency is not likely to make much difference to this.

Most of the schemes being set up within the Transition Towns movement seem to take this substitution form. The websites enthuse about positive effects on morale but give no explanation of how these new notes are supposed to improve anything. Just substituting one note for another can’t create or change any economic activity, let alone get unused resources and unemployed people into production. The morale and publicity benefits are good, but these can also attach to useful forms of currency. Eisenstein calls these “proxy currencies” and sees that they can do little or nothing to improve a local economy. (2012, p. 303.) The study by Marshal and Oneil (2017) found that they make little or no difference.

Similarly some a town councils print new money and get it into circulation by using it to pay (part of) the wages of their employees. This again just substitutes new money where old money was being used, and circulates it via rate payments, creating no new production, infrastructures or jobs and doing little or nothing to make the town more self-sufficient.

Another monetary innovation unlikely to have desirable effects is to adopt a currency which depreciates over time. This does little more than encourage people to spend money faster than they would have, generating more economic activity. But it’s wrong-headed to encourage spending; people should buy as little as they can, and any economy in which there is a need to consume in order to “create jobs” is a silly economy and should be scrapped. In a sensible economy there would be only enough work, producing and spending and use of money as was necessary to ensure all have sufficient for a frugal but good quality of life.

An increasingly popular approach is where ”anchor institutions” such as hospitals which receive large incomes from the state switch some of their purchasing to local sources. This can increase local economic activity, but only by transferring purchasing from the previous distant sources, and putting people there out of work.

The important point is that none of these approaches produces a net increase in jobs, incomes or economic activity, and all except the last do nothing to help build a more self-sufficient local economy. How then might a monetary system be used to do this?

So, how to proceed?

As stated above, the focal concern must be trying to set up new productive ventures which enable people who were idle to use resources that were idle to provide some of the things they and the town need. The elementary example is the setting up of a cooperative community garden so that people who had no employment can start working together to produce some of the food they need. The time contributions of participants can be recorded and the eventual produce shared accordingly. That is, a LETS–type of money is used to keep track of contributions, “earnings”, credits and debts. Surpluses can be sold into the conventional economy, accumulating normal money to put into purchasing crucial inputs needed from that economy, such as more tools.

Of course many communities are doing this and related things that go far beyond food production. Community gardens can easily add on workshops, repairing, recycling, furniture making, bike repair, bakeries, services and building simple dwellings and premises.

The best unit of currency would seem to be some kind of “time dollar”, that is, one hour’s contribution in the garden earns as much credit as one in the bakery, regardless of the skill levels involved. This enables many different businesses to participate in the community’s system. A business or individual can operate with either the new or old currency, or both.

Our new money will only be useful within our town or small region. A distant cement works isn’t going to accept payment in our currency, because it can’t use it to buy things it needs, like limestone. I think that in the longer term future we will operate with two currencies, firstly our town currency for use in buying and selling most of the things we need because these will be produced in the region around our town, and the national currency for purchasing the few things that have to be produced further away in the national economy. This means that all towns or regions must have within them some productive activities that can export into the national economy to earn the national money needed to import necessities they can’t produce. There will be relatively little need for these activities because again most of the things we need for a good life are easily produced locally.

This two-currency situation will ensure that we attend to the local “balance of trade” and keep it in good shape. If our town does not produce and export enough into the national economy we will not earn enough to purchase necessities from it. The town bank would watch the accounts and let us know if our imports are tending to exceed our export earnings. A major function for the (small remnant) state and national governments in the new society would be to help the town to set up a few more productive activities to export necessities into the national economy. Obviously the distribution of these opportunities would have to be carefully planned and regulated to make sure all regions had a sufficient share of the production needed in the national economy. It would not be acceptable to allow those most able to produce cheaply to take all the opportunities, leaving others with insufficient capacity to contribute and pay for what they must get.

This need to keep an eye on the town trade balance would be an important constant stimulus to thinking about maximizing town self-sufficiency. Can we reduce our need to import and thus produce exportable items by increasing our capacity to produce what we need here?

What should local councils here and now be doing to facilitate all this? Firstly they should establish an electronic LETS-type of currency, so that payments and earnings can be recorded quickly and conveniently. Participants might pay a small annual fee in this currency to cover the administrative costs, which the council could spend purchasing things participants have for sale, especially labour. This is basically just like giving everyone a cheque account, with rules to do with guarantees and limits on debt.

Secondly, councils should provide the small amounts of normal-money capital to help set up appropriate new firms, some private and some co-ops. That is, they should enable start up of firms which are going to produce necessities from local inputs and provide jobs for people who don’t have them now. This should be done in the light of a long term sustainable development plan for the town, which would involve working out which small farms and businesses are needed to increase town self-sufficiency, and to produce a few exports into the national economy.

A major reason why councils should fund such projects is that they would greatly reduce much of the town’s present damage control expenditure, e.g., on dealing with crime, violence, police, courts, jails, mental illness, alcoholism, drug abuse, hospitals and “welfare”. Obviously the more that dumped people can get into new little firms and co-ops providing worthwhile activity, income, company and self respect the less likely they will add to “welfare” bills. (Many trials of a “Universal Basic Income” are underway. There is evidence that the cost is likely to be far less than the reduction in expenditure on all these problems. Gardiner, 2016.)

In Simpler Way transition theory (TSW, 2018b) the crucial task is building an Economy B underneath the existing mainstream Economy A, with a view to gradually replacing much of the latter. Because Economy A fails to attend to many important needs we are going to do what we can to set up our own arrangements to meet them. These will contradict the principles that drive Economy A. For instance, what is done will be decided by rational discussion of what is best for the town, not by profit or market forces or what private banks want to lend for. No one will get any interest, or any income without working for it. Non-monetary values would override monetary values; we would do what is good for people and the town and not what makes most money. Development priorities would be set by rational town discussion, not by investors focused only on what will maximise their profits.

In the long term future?

Even though we will have a large and powerful Economy B, providing all those things needed for a good quality of life that Economy A ignores, and preventing the damage it does, there might still be a large Economy A. That is, many (unimportant) things might be left for markets to determine, so for instance someone might try setting up a dress making, or adventure tours or wine making business, to see if people want to spend some of their disposal income on these things. Over the longer term experience will show how much activity is best left to Economy A. (And in time we might find that we don’t need money at all…in an economy where what everyone needs for a good simple life is easily provided by relaxed contributions, just like in good family.)

In my view in post revolutionary society most productive capacity should be owned and run by small private firms and co-ops, operating under guidelines set by town assemblies. This would enable people to enjoy running their own little farm or shop as they wish. No one would want to take over lots of other firms and become a tycoon (…or be allowed to…we wouldn’t buy from him.) The productive activity needed would be shared among all wanting to contribute; a major priority would be to make sure everyone had a secure livelihood. There would be no such thing as bankruptcy or unemployment. The town needs to look after everyone and make full use of the labour and talent it has. If a firm was getting into difficulties the town would have to work out what to do, maybe organise advice, loans, training, merging or helping people to move to other activities. The ethos would be that this is our cooperative town and everyone’s welfare depends on us organizing to make sure it thrives and all are provided for, so we are all happy to contribute to meeting its needs. We would realize that there is no point in trying to get rich; our wealth, the richness of our lives, would take the form of our beautifully gardened town, our supportive community, our access to good conversation and skilled art and craft teachers, the time we have to think and learn, our security knowing there is strong concern to make sure everyone is OK, and the peace of mind that comes from knowing we are living in sustainable and just ways.

Eventually all banks will be publicly owned. For years Ellen Brown (2018) has been telling us how the Bank of North Dakota is the best performing bank in the US, facilitating lots of good things … because it the only bank in the US that is owned by the state. That means no earnings flowing out to shareholders. It also means the people through their representatives on the board can make sure money is lent for socially desirable projects.

What many monetary reformers don’t realize is that in a zero-growth economy the entire problem of money creation and fractional-reserve banking will not exist. There will simply be no need to create any more money! Our town economy and the national economy will only need a certain constant volume of money circulating to enable the constant amount of purchasing and developing going on in an economy that is relatively small and never grows. There will be very little need for lending and investment. Most of it will be going into maintaining the small amount of low-to-intermediate-tech productive capacity that would be needed, and adjusting/improving it. Democratically controlled community banks with elected boards will decide what purposes loans are given for, and borrowers will pay no interest. Money will just be a device enabling us all to keep track of what we owe or are entitled to. No one will worry about not being able to get enough money to sustain their delightful but frugal lifestyles, because there will be no unemployment or poverty, because communities will have the sense to make sure everyone has a livelihood enabling everyone to make that small productive contribution needed to maintain the local economy in good shape. That will require us to work for money maybe only a day or two a week, so we will be able to spend the rest of it fishing, painting, reading, gardening, sitting in the sun…

Brown, E., (2017), “The Public Bank Option – Safer, Local and Half the Cost, The Web of Debt Blog, November 4.

https://ellenbrown.com/tag/bank-of-north-dakota/

Gardiner, S., (2016), ”On the Canadian prairie, a basic income experiment”, Market Place, December 20, https://www.marketplace.org/2016/12/20/world/dauphin

Kennedy, M., (1995), Interest and Inflation Free Money: Creating an Exchange Medium That Works for Everybody and Protects the Earth, Seva International.

Marshall, A. P., and D. W. Oneil, (2017), The “Bristol Pound; A tool for localisation?”, Ecological Ecnomics,146, 273-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.11.002

TSW 2018a, The Simpler Way. http://thesimplerway.info/htm

TSW 2018b, The Transition Process: The Simpler Way Perspective. http://thesimplerway.info/TRANSITION.htm