People come from over 30 countries to live in Toronto’s Black Creek community.

The community is known to most outsiders for what it lacks — people who make a lot of money. Like any community, the people of Black Creek would like to be known and respected for what they have.

I learned two things about assets of Black Creek. One: people here know how to organize a fun and effective day-long meeting about a painful, complicated and all-too-common problem — hunger! Two: local residents come out, stay all day, and leave uplifted when they see people like themselves offered a safe space to talk in plain language about their needs, worries, hopes, and dreams. Black Creek has these experts.

Though I’ve been going to and organizing meetings and conferences for half a century, leaders of the Black Creek community taught me six major lessons about how to plan and hold a successful meeting. I think those lessons can benefit food organizers anywhere in the world. So I’m going to share those lessons here.

TAKE ADVANTAGE OF WHAT FOOD OFFERS

The beginning of wisdom in organizing a food meeting is to appreciate that meetings dealing with food — unlike meetings taking up other important issues, such as transportation or energy–deal with an issue that is very close, personal, and visceral. Food meetings, therefore, have the opportunity to tap into several layers of personal and group experience and appreciation at one time.

At the surface level, a meeting about food is about a topic related to food, such as the lack of a quality food store in the community or the need for more public gardening spaces. The advantage of organizing a meeting on such topics is that they can unify the entire community behind a basic essential of life that affects everyone and is shared by everyone.

But just like an iceberg which is nine-tenths below the surface, nine-tenths of any food theme is below the surface. Skilled meeting organizers can put these invisible forces to work. Aside from sharing information about a common essential need for physical survival, a food meeting can provide a meal before, during or after the formal meeting. A meal can do more than provide fuel and filler. It can meet emotional needs by bringing people together to bond as a community through the pleasurable social experience of sharing a meal. In other words, a meeting can be both about and with food. Likewise, a meeting can share information and knowledge throughfood. People share knowledge through food in the course of eating meals that respect and bridge diverse needs in a community by offering vegan, halal, kosher, and a range of ethnocultural dishes. Furthermore, a food meeting can deepen and broaden its impact with meal experiences that model how to act on food, perhaps by offering meals from local and sustainable caterers that are served in reusable or recyclable containers. Such actions benefit community actors and increase neighborhood capacity in a casual way.

Finally, sharing food is a uniquely human experience. Breaking bread together teaches many special truths about individuals and groups. Eating is a performative language. A shared meal models how we can care for one another, accept one another, and learn from each other. It is a “significant communicative and interactional practice,” Brigida Marovelli argues. The very act of eating creates a “congregational space” and a “space of possibility,” she says. It creates “spaces of encounter, facilitating communal ways of thinking and acting.”

In sum, mealtime and snack time during a meeting gives meeting organizers a lot of on-topic and on-message opportunities to deepen and enrich a meeting’s theme.

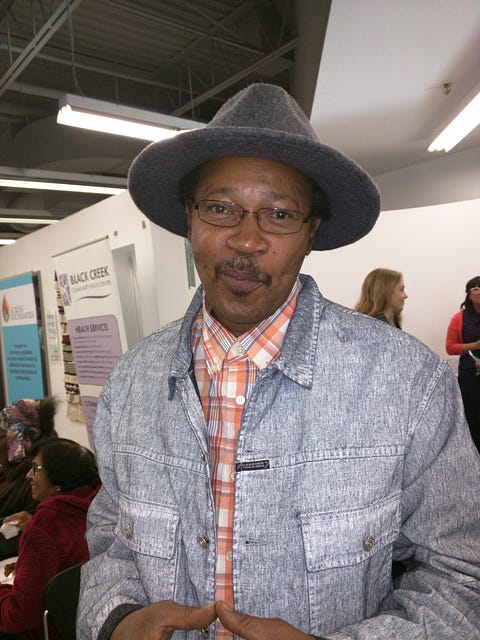

A MEETING THAT WAS MUSIC TO HIS EARS

Anan Lololi lives in the neighborhood and was the anchor organizer of the Black Creek meeting. He first kept in touch with his Caribbean roots by playing bass guitar in a highly-regarded reggae band called Truth and Rights (see one link here). But for the past 25 years, he’s become better known for banding together to grow food. He loves to grow and eat vegetables that were the comfort food of his youth in Guyana. He has a passion for helping people in the community grow and buy traditional, nourishing and African heritagefoods. The can-do organization he’s known for is called AfriCan Food Basket.

Anan loves gardening, but the longtime musician also likes record launches for Bob Marley…and meetings of the Black Creek community.

Anan says the October 20 meeting about food and health at the Black Creek Community Health Centre “felt like the release of a new Bob Marley record!” It helped a lot of people to get up, stand up.

I feel just as pumped as Anan.

I have my own reason for wanting to know the secret recipe for a successful meeting like that.

I am one of the most experienced people in Canada when it comes to suffering through dreary meetings.

During 50+ years of being active in various social causes, I’ve endured an average of two meetings a week. I know more about bad meetings than almost anyone.

This Black Creek meeting was one of the most successful of some 5000 meetings I’ve been at. I want to find out why.

HOW I LEARNED TO DO MEETINGS

I applied my meeting know-how to the Toronto Food Policy Council, which I managed from 2000 to 2010. Our meetings were always well-attended and many people said they got high on the spirit of those meetings.

Here are a few of the meeting tricks I used. I have six more to add after the Black Creek meeting.

First, we took full advantage of email to send TFPC members a full accounting of all sorts of matters that normally take up at least 15 minutes at the front-end of meetings with boring necessities — such as agreeing on the agenda, reviewing minutes and follow-up from previous meetings, and so on. As is often done in formal City of Toronto meetings, we dispensed with these sleeper issues in a few seconds by wrapping them all up in one motion called a “consent agenda.” Members learned to read over boring and routine information before the meeting and vote quickly on one general go-ahead motion.

With the time we rescued from administrivia, we launched meetings with 15 minutes of sociable networking around fair trade coffee and tea and fresh-baked cookies from the farmers market, together with 10 minutes to present our local food hero award” to a deserving farmer, processor or retailer — a positive and upbeat way to start the meeting. Right after the break (just to make sure people came back after the break), we featured a 20-minute presentation of new and original research and analysis on an exciting food topic, as well as ten minutes of discussion.

I came to these methods because I realized that TFPC meetings had to compete for peoples’ time. The people who might come to meetings usually have two other choices of what to do with the time they might spend at meetings. They have a to-do list of essential deadlines people. And they have an R & R list of pleasant ways to spend time with friends and family.

How do we compete with items from those two lists? To win out, our meetings must be more indispensably useful (exclusive networking opportunities and the latest insider info on events and trends, for example) than deadlines. To win out over a movie or meal with friends, our meetings also had to offer more pleasurable opportunities to meet interesting people, hear about exciting and uplifting projects, have a few laughs, and eat some tasty snacks.

In short, planning a meeting is about finding a competitive edge in both usefulness and pleasure.

I learned many more successful meeting tricks than this from the meeting at the Black Creek health center.

When 150 people of different ages and backgrounds can spend most of a day learning about dispiriting and complex topics such as hunger and health, and come out of that experience feeling like they were at a launch party for a hot band, we can all learn something about event organizing.

Here are the six tips I learned. I think they can apply to any public meeting or mini-conference on food.

Anan Lololi will be the first to say that it’s not enough to know these rules. His years as a professional musician taught him that progress is made through practice. “You have to practice how we bring people together and how we talk to one another,” he told me.

DO WE REALLY NEED ANOTHER MEETING?

Tip 1: The first thing a meeting organizer has to do is bring together all the people who will be involved in making the meeting happen. Force them to come up with a good list of reasons as to why a meeting is the only way to accomplish specific purposes that will benefit the people coming to the meeting. The meeting has to meet the needs of the people coming to the meeting, not the organization sponsoring the meeting.

Meetings should be seen as a last resort. That’s because a successful meeting has to attract people who are not the “usual suspects.”

The people we need to come to meetings have all got 15 better things to do with their scarce personal time than come to a meeting. If the meeting isn’t more important than doing the laundry, cleaning the kitchen, taking the kids for a walk, going shopping for food, watching the soccer game, having a snooze, getting bills in shape for a tax audit, or helping grandma with her cleaning, then the meeting won’t make the cut.

In other words, the first thing needed for a successful meeting is organizers who put the needs of their clients or customers ahead of some abstract formula requiring a meeting.

This is a basic principle of modern marketing: motivate the customer by selling the benefits. Come to the meeting because it meets your needs. If the claim is true, it saves organizing time and leads to a successful meeting.

Likewise, the staff people who will be run ragged getting the meeting together need a good list of reasons why 60 days of collective worktime and a few thousand dollars can’t be spent in better ways than on a meeting. Especially in this age of interactive communication, we need to be able to explain why a telephone survey isn’t a better way to get feedback on a proposed project, or why a three-minute video with basic information can’t get out to more people more effectively than a meeting. Here’s one example of how an alternative to meetings can be pulled off. (For another excellent guide to workplace meetings, see here. These guidelines can all be adapted to public meetings.)

If the proposal for a meeting flunks either of these tests, cancel the meeting. Build a reputation that you only organize a meeting if it’s essential.

In the case of the Black Creek meeting, the community health center had a compelling reason to hold a meeting. The Centre wants to engage the community in a basic shift in healthcare practices. Instead of spending most health dollars and resources on trying to reverse diseases that are causing people lots of pain and difficulty, they want to spend more money and resources on preventing disease.

Cheryl Prescod, ED at Black Creek Community Health Centre, doesn’t like meetings. But meetings are the best way to get the community truly engaged and taking charge.

The best way to manage that shift, according to Cheryl Prescod, executive director of the community health center in Black Creek, is to work on food projects that make healthy food more available and healthy food choices more appealing.

Before she invests more into that shift, she wants to be sure the science is there, and that community members are keen to take part. (Full disclosure: both Anan and I are working on a research report for the Centre that will provide evidence supporting such a course of action.)

That’s a strong reason for a meeting. An important and controversial decision has to be understood, discussed and approved. And community health center actions need to flow from those discussions.

There’s a related decision that’s just as important. It has to do with a basic reality of food. Failure to understand this basic reality lies behind the failure of many government programs in the food area. Good meetings are a good way to avoid this failure. (For the basics of event management, which are not presented here, see here.)

GOOD MEETINGS LIGHT FIRES

Here’s the basic reality: with food, nothing happens, except on paper, until people engage. Having the health center send out a leaflet on why you should eat healthier foods doesn’t do any good unless people have the money for healthy food, a convenient place to buy it, the skills to prepare it, the time and appreciation for enjoying it, and a commitment to making it a habit. People in the community are the only ones who can make this project work. So they have to make a decision for themselves. They have to claim their own agency. And they need to know that if they do make a move, they will be supported by others in the community, as well as staff at the health center.

Keynote speaker Fiona Yeudall of Ryerson University’s Centre for the Study of Food Security reminded people of food ideas that were recently inconceivable but are now being acted on.

It’s as simple as that. A mom who wants to breastfeed her child understands why it’s important for the lifelong health of baby and mom. She needs support from the health center if she runs into difficulty. She also needs support from other family members, because breastfeeding is a priority that takes time and energy. She needs support and friendship from other breastfeeding moms. She also needs support in the community because she will often need to breastfeed in public, including at meetings.

So decisions on healthy food policy are also deeply personal policy changes. And people need to talk about that. That’s why meetings to open up that process are fundamental.

In this age of the Internet, we don’t need to meet in order for people to receive information. We need to meet because people need to talk as well as listen, and because people who run official programs need to listen as well as talk.

These are compelling reasons to hold a meeting, devote health center resources to it, and ask community members to donate their time to it. That’s why Cheryl Prescod’s opening welcome at the meeting invited people “to listen to each other with open minds, but open hearts as well. It’s important that we listen” to each other, she said.

GOOD MEETINGS ARE CURATED, NOT BORN!

Tip 2: Focus more on curating than on organizing the meeting. For conventional organizers, that’s a real mind flip.

Organizing is about informing and persuading people to come to your meeting and making sure all the tables, chairs, rooms, speakers and facilitators are properly prepared so people can learn more about a topic and be inspired to take action.

Curating is about creating an experience that attracts people to engage at several levels, and making sure the event is designed to meet a variety of peoples’ needs, not just the organizers’ goals. To use biz-talk, curating is customer-focused, not task-focused.

We’ve long known how to curate objects for tours. Now we need to learn to curate meetings for participants.

Curating a meeting shows the same approach to people as museum curators or art gallery curators show with their displays. Good curators make sure everything is laid out so that people are shown the way to have a real experience with the items on displays. Curation makes sure the display is laid out to foster a relationship with the people enjoying it.

This approach to meetings goes with what I call “people-centered food policy.” Food isn’t just about the logistics of providing an output for agriculture and processing or input for nutrition. It also brings people together, supports conviviality and countless rituals of celebration, romance, togetherness, and reflection. So curation of a food meeting needs to be as wide and deep as people’s relationship to food.

Curators of food events need to have a front-of-mind awareness that there are almost as many reasons for coming to the meeting as there are people who come. The event must provide multiple layers of experience opportunities to embrace the wide variety of the motivations for coming to the meeting.

This is especially important for food meetings. Some meeting analysts working in non-food sectors can think in terms of distinct streams of people who come to a particular meeting for a particular reason.

Louis Rosenfeld distinguishes between tribal events, networking events, trade show events, educational events, and academic events. Each type of event requires a different approach, he argues.

This approach can never succeed with food because people come for all of the above reasons, plus one other big one — to enjoy some food together. A well-curated event must appeal to all of these goals. It cannot just focus on one audience or goal. That’s why food meetings are more difficult to organize than other meetings. Food movements are about creating a majority of minorities — people from many backgrounds and with many motivations who all share in their own way from the benefits of a specific food program.

For example, the successful meeting in Black Creek had a major audience mix. I noticed old and young community members, academics, community agency staffers, food and gardening enthusiasts, and activists from the community group, Jane Finch Action Against Poverty.

I realized another dimension to curating rather than organizing meetings in today’s world following an eventful meeting of Food Secure Canada (FSC) a few weeks after the Black Creek meeting. In today’s world, thankfully, most meetings are required to deal with tough relationship issues that were often overlooked or glossed over in the past. Many of these tough issues have to do with longlasting damage and hurt caused by white, male, and heterosexual (aka privileged) dominance. Given that food is very much about relationships, it’s both essential and positive that food meetings feature sessions that explore and address such issues. This requires skilled curation to ensure productive conversations.

After discussions with Halifax food and ecology leader Satya Ramen, who co-moderated a FSC session with me, I would say modern meetings need to be curated to meet these modern needs. Meetings need to be scheduled with time, space, and seating arrangements appropriate for a safe airing of grievances on sore and touchy issues. It is no longer sufficient that meetings deal only with “content” issues, such as information-sharing and preparation for mobilizations and campaigns. There has to be time and space for “deep listening” to “process” and inter-personal issues, such as feelings about domination. There should be a way to arrange chairs around a circle, instead of more hierarchical ways.

We will learn to respect both sides of the brain — the right or emotional side, as well as the left or so-called rational side. We may also need to address behaviors reflecting privilege and inequity among progressive and well-meaning individuals. However much a person considers himself or herself to be a “left-brained” individual, the inner right-brained and emotional self quickly rears its head during such sensitive discussions.

Positive and healing outcomes depend very much on effective curation, not just organizing. That’s because space and time need to be provided for listening and conversation, not just speaking and discussion. Anan Lololi reaches for a way to explain this that comes out of his background in music. Music is about communicating, he says. “If you want to do it well, you have to practice,” says Anan, lead organizer of theBlack Creek event, as well as a major participant in the FSC conference. “It’s the same with meetings. You have to do your ten thousand hours.”

MEETINGS MUST BE MULTI-FUNCTIONAL

Food meetings have this quality in common with spaces in a city that are referred to as “people places.” Experts at the Project for Public Spaces know what makes a successful place. According to them, a dynamic place needs to invite people to join in for at least ten reasons.

When I think of that, my mind goes to the very busy city hall in my hometown of Toronto. There are easily ten reasons to come there — to do an errand, attend an event, meet someone, or find something to do. There’s a great rink there in the winter. There’s a farmers market every Wednesday. There’s a band shell for whatever celebration is going on in the city, whether it’s support for a sports team or festivities on New Year’s Eve. A café and library are on the main floor. There’s a public washroom in the basement. There’s a green roof on the third floor. There’s a children’s playground at the side and a childcare center at the rear. You can get married there. You can pay utility bills and parking tickets there. There are often displays in the rotunda.

Did I almost forget meetings of City Council and its committees, offices of councilors and civil servants, meeting rooms for citizens making deputations to persuade City Council meetings about something, and public meeting rooms for citizen groups? And because of all the above, there is lots of people-watching, especially among tourists.

You might not be able to beat city hall in Toronto, but there are lots of reasons to be at Toronto City Hall.

A food meeting needs to be curated like a people place because that’s what a food meeting is.

PUT MEETINGS IN THE COMFORT ZONE!

Tip 3: Make sure people are comfortable. Focus as much on making people comfortable as you focus on making them listen to the speakers.

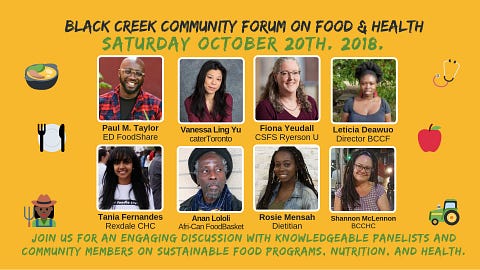

Check the poster for the Black Creek event. It’s very basic, nothing fancy.

simple, colorful, inviting: not a stuffed shirt to be found!

The faces on the poster are mostly people from the community. They’re all casually dressed. Not a stuffed shirt amongst them. They’re all ages and hues of the human rainbow. At least one of them looks a little bit like you on a bad day. If you have any questions, the person to phone is referred to by her first name. Yes, we still take personal calls.

The meeting is held at the community health center, which most locals are familiar with, and feel safe and comfortable in. It’s not at the nearby university or museum.

There’s a hot breakfast with a variety of offerings, including pastries, to greet you in the morning. Don’t worry about making time for breakfast at home, and don’t worry about being judged for your food preferences. Don’t worry about whether you’ll find someone to sit with. Don’t worry if you’re new to the neighborhood. The breakfast is a stand-up community event.

The chairs are comfortable. The washroom is nearby. The same people who greet you at the health center are greeting you here. The director of the health center is casually dressed and welcomes you as you come in. Childcare is available. The conference room is in a shopping mall, so you can find time to do your shopping on the way home, and you don’t have to worry about getting lost.

For people who have a lot to worry about, especially money worries, it’s nice to come to a gathering place where there will be no worries. The organizers respect that your life situation entails enough things to worry about without having a worrisome meeting to add to the list.

Cheryl Prescod, head of the community health center, considers a neighborly atmosphere is essential when working with disadvantaged people. “People living in poverty not only face tough problems like unemployment, racism, hunger, and difficulties with the English language. They also have to face officials who don’t sympathize with their plight And at the end of the day, they have to face a mirror and not feel embarrassment, stigma, and shame,” she says. Meeting organizers need to be sensitive to such realities. “That’s why we have to create a warm and welcoming environment and also make sure food is provided,” Cheryl says.

BELIEVE IT OR NOT: MEETINGS CAN BE FUN

Tip 4: Successful meeting curators are intentional about having fun. Spend as much time on curating a fun experience as you spend on the formal “main event.” We need to take the informality as seriously as the formality and treat fun as seriously as note-taking.

Shannon McLennon, breastfeeding consultant at Black Creek health center talk about tough discussions, and Vanessa Ling Yu of Cater Toronto talks about big obstacles, but they’re happy warriors. (photo by Errol Young

I thought that way about monthly formal meetings of the Toronto Food Policy Council when I managed the Council from 2000 to 2010. As I saw it, we were in competition with TV and videos. To lure people away from their screens, we had to be more entertaining, more relaxing, more pleasant, more energizing than sitting on a sofa, munching on potato chips and laughing at a comedian. Otherwise, people wouldn’t come back and wouldn’t invite their friends to join them at the next meeting.

People who are really struggling to make ends meet enjoy a good laugh. It’s the cheapest and best entertainment in town. They might not have a sofa where they can lounge in front of a big screen TV and satisfy the munchies. They need a little joy in their lives. We need bread, but we need roses too, the old labor slogan had it. We need to be “happy warriors,” was how American Depression and World War 11 President, Franklin Roosevelt, put it.

Clifton Joesph can’t get his tongue out of his cheek; he’s always on the edge of seeing and saying something funny. Here’s what he said about the day on Facebook: “ It was wonderful like Stevie..ravenous like marvin and respectful like aretha…and oh/sofabulous”

One person takes the cake for making the Black Creek meeting fun — Clifton Joseph, bringing his national reputation as a dub poet and broadcaster and his local reputation as a gardener of African-origin produce. Clifton Joseph wore a dramatic hat all through the meeting and used his gifts as a dub poet to rhyme off funny one-liners that delighted and energized the audience throughout the day.

Meeting analyst Louis Rosenfeld, mentioned earlier, makes the point that bad jokes are an important asset of meeting emcees because they distract the audience from a glitch here and there without stealing the spotlight from the speakers or audience. A similar trick is played by Cirque de Soleil performers. Once or twice over an evening, a performer slips and falls from the highwire, catching the wire at the last instant. The audience gasps, not knowing the slip was deliberate — part of the expertise of the performer, who needs to show the audience that only skill saves performers from certain injury and death.

Clifton Joseph has the same level of skill when it comes to bad jokes. But he was so enthusiastic and transitions moved so smoothly that the bad jokes became in-jokes.

The bad jokes also distracted from the stern way Joseph enforced strict time limits on speakers.

Too many meetings tolerate speakers who haven’t rehearsed and don’t know their talk will drag out way beyond what the agenda allows, leaving other speakers in the lurch, and forcing the audience to give up break times. Not Joseph.

Joseph also had a grip on what documentary and stage producers call “production values.” Speakers are performers, and professional performers understand production values. Think of Shakespeare. Right after a few minutes of intense drama comes something light, trite and bright. The same pacing happens on TV news.

A meeting is a performance. It needs to be staged as much as any form of live theatre. The emcee needs to direct the same level of teamwork, synchronization, rhythm, and excellence as directors demand in any professional performance. Because the key job of the meeting emcee is to champion the audience’s enjoyment of the meeting. (For the role of emcees, hosts, or moderators, see this)

After seeing Joseph work the room, I would argue that all successful meetings need a professional and independent emcee. They do a lot more than entertain and move the agenda along. They give confidence to the audience that the meeting is being run by an independent professional who has only one agenda — a meeting that succeeds equally for the organizers and organized.

GOOD MEETINGS INSPIRE

Tip 5: A good meeting engages the heart as well as the mind of the audience. Professional speakers always take care to speak to both the left side of peoples’ brains (the rational side that wants facts and statistics) and the right side (the emotional side which craves stories that speak to the heart). Meetings need to maintain the same balance.

The highlight of the Black Creek event was the mid-day panel featuring young people from the community. Their stories of challenges they overcame as they sought career and business opportunities inspired admiration, confidence, and hope in the entire audience. Everyone sat another few inches taller on hearing them.

Such transformative learning is best experienced through personal story-telling. “The I’s have it,” says Michael Pollan, an influential journalist, author of several best-sellers and producer of several powerful documentaries who has taken radical food movement messages to tens of millions.

Pollan knows that every good argument has to be backed up by a good story that gets up close and personal to explain why something has to change. That human need for a story comes goes back to the earliest food experiences in human history, when early humans huddled around a fire every night to tell stories to each other and celebrate another day of successful life together. A meeting without stories is lacking a deeply-felt human need to connect on that level.

John-Terre Shorth (known as JT) led off by recounting his three teen-age years on the farm team at Black Creek Community Farm (see here and here), one of the more beautiful sites in the community. He learned about agriculture, permaculture, and food handling. Now, he’s training to be an electrician, but he hopes to take up farming as soon as possible. “Being a Black youth, I want to contribute to be part of the food system,” he said, because “culturally-appropriate foods need to include Black cultural foods.”

Vanessa Ling Yu, who grew up in a family that ran a Chinese restaurant in rural Nova Scotia, knows what it’s like to feel alone and different. She set up Cater Toronto to support racialized women, and offer them the business training they need to provide “feasible and feastable market opportunities.”

Rosie Mensah grew up in Black Creek. She didn’t know she was from a poor family. “ We were all poor,” she said. Having struggled with obesity in her ‘tween years, she understood when she entered nutrition studies at university that food was not just about nutrition, but about identity, culture, and history. She has now earned a Masters of Public Health, has been a member of the Toronto Youth Food Policy Council and serves on the Board of FoodShare, Toronto’s (and North America’s) largest city-based food security organization.

Tania Fernandes wants to create opportunities for young people in nearby Rexdale. (photo by Errol Young)

Tania Fernandes, the organizer of the locally popular Rexdale Food Festival, also grew up in the neighborhood. As a result of growing up in an impoverished and ethnically-diverse neighborhood, she felt both racially isolated and socially belittled on many occasions when she started at university. She now works at a community health center to “create opportunities for kids to grow up feeling confident.”

How can anyone not be inspired by this picture of Black Creek farm youth? That’s Letitia at the top left, and JT, at the bottom, middle.

Letitia Deawuo is executive director at Black Creek Community Farm, which she described as a 4.5-acre site “where people can come together and look at deeper issues” related to the racialization of food insecurity poverty. “The farm is a space where people can come together and create a fair and just system that serves everyone equitably,” she says.

Fiona Yeudall, a nutrition prof at Ryerson and head of the university’s Centre for Study of Food Security, brought the same can-do approach to progress made on the food file. Not only did Yeudall’s overview of food security add the credibility of a widely-respected academic to the causes raised by Black Creek community members. She also encouraged community activists to keep on pushing. “It’s not that long ago that many projects were considered inconceivable, but are conceivable today,” she said, pointing to recent successes in having nutrition labels placed more prominently on packaged foods.

Many leaders of the global peasant movement, Via Campesina, are sticklers about not using the word “poor” to describe people on low income. They are not poor, Via Campesina leaders, say, they are impoverished. Poor is a passive noun. Impoverish is an active verb. People are not poor; they have been made poor, these leaders insist. These peasant leaders are challenging the fatalism that so often travels with poverty.

The stories of people on low income who have overcome the barriers have the same effect here in North America, and every meeting needs a dose of that.

This powerful session was a case study of the power of narrative and story-telling, a form of sharing ideas and information that’s been revived and celebrated recently (see here and here and here, for example) thanks to social media and the likes of TEDx. Food is meant to be discussed in the course of stories, not lectures, and it’s time public meetings put this method of information sharing at the center of the meeting agenda.

Tip 6: FORMAL MEETINGS MAKE SPACE FOR INFORMAL LEARNING

Shirley Sparks was there for the day. Speaking of informal learning and teaching, she’s one of the people who sparked me to think in terms of people-centered food policy.

Shirley Sparks was there for the day. Speaking of informal learning and teaching, she’s one of the people who sparked me to think in terms of people-centered food policy.

A successful people-centered meeting needs space for participants to do their own learning from each other, at their own pace and on their own time. Informal learning is as important as formal learning, educators now recognize. (See for example, here and here.)

It’s the job of meeting organizers to give participants time and space and to facilitate the productive use of that time and space. That’s what happened at the Black Creek meeting.

Meals served for breakfast and lunch provided a free time when people could mix. Several people, including Cheryl Prescod and me, kept an eye out for anyone who needed an introduction to someone who shared a common interest or background. Every successful meeting needs social butterflies to pollinate.

Networking takes that to another level of group empowerment. Following the panel of young professionals, I suggested casually to a few of them that they all get together and form a group that could present itself to the Ontario Public Health Association, and ask for status as young professionals in underserved communities.

Gurneet Dhami and Rosie Mensah, two local women making good in health professions, report back on their hopes to link up with the Ontario Public Health Association. Here’s what Gurneet posted about the meeting on Facebook: “It’s not every day your food heroes gather up in one spot! Seeing my teachers, colleagues, mentors, (new) friends and community members gather in one place on a fine fall Saturday just made my heart smile.”(photo by Errol Young)

I know that the Association responded positively to a group of us asking for status to form a formal subgroup on food security about 16 years ago, and the positive memory of that was rekindled by hearing the young panelists. I’m looking forward to seeing that go forward.

That’s the kind of project that can get airtime if meetings adopt what’s called “open space technology.”

Some meeting organizers realized that the best discussions at a conference were happening in the hallways, not the meeting rooms, and proposed that meetings feature a call-out when someone can ask people who want to talk about X should follow them to Room 1 and someone else suggests Y topic for Room 2, and so on. That’s participatory democracy, and every meeting should have some way of embracing that spirit, if only by providing lots of free time.

The Black Creek meeting organizers figured out another way to make use of free time. Several clinicians were available to take tests of individuals. Almost everyone knows they need to get their blood pressure and sugar levels checked, even though they can never find time to go to the health clinic.

Well, the perfect time to do that is when you’re already at the clinic for a public meeting. A meeting that can help with multi-tasking is a useful meeting.

Many of these meeting features flow from the commitment to a customer focus when planning out the meeting. Meeting organizers may have in mind some core ideas they want people to hear. But meeting curators know that people come to meetings because they also have something to say and they want to be heard too.

GREAT MEETINGS END EARLY

As a final sign of consideration for the audience, the meeting was organized to end early in the afternoon, leaving enough time for errands and other matters that are expected to get done on a weekend. However good the meeting, you can have too much of a good thing.

Ending early is one of the best ways to end a successful meeting.

“We’ve got to stop meeting like this” is a standard phrase in comedies, when two people keep bumping into each other at inconvenient times.

I always thought the same phrase applied perfectly to many of the 5000 public meetings I’ve attended over my life.

But now, I feel the opposite. After the Black Creek meeting, I would say “we’ve got to start meeting like this more often.”

CHECKLIST TO PROJECT MANAGE A SUCCESSFUL FOOD MEETING

Initial Strategizing:

- People assigned to plan the meeting need to identify direct “hard” objectives (secure a credible community vote to start a campaign), indirect objectives (media coverage), as well as “soft” objectives (a chance for “the tribe” to enjoy each other’s company and renew commitment). Given the cost and effort necessary for a successful meeting, have you determined that the objectives warrant the expenditure, and there is no other way to meet these goals at a reduced cost of money and time? If so, can you name a project manager for whom the meeting is a priority?

- Can you find a meeting place that is conveniently accessible and welcoming, especially to people who are disadvantaged?

- Can you subsidize admission costs to ensure that the meeting is accessible to vulnerable community members?

Event Planning:

4. Can you provide food and snacks to add to the welcoming atmosphere of the event and ensure attendance by people facing food insecurity challenges? Will you advertise this? Can you ensure that the food and snacks express values of the organization? Can you attract sponsors who will provide some of the servings at a reduced cost?

5. Can you arrange for a prominent and respected person in the community to welcome people to the meeting so that people have a signal of the importance of the event and its likely impact?

Outreach and Promotion:

6. Can you identify social media posts and listservs that will reach the major audiences for the meeting? Can you develop an attractive poster that can be posted in prominent places throughout the affected communities? Can you arrange for prominent speakers and guests to use their personal communication channels to promote the meeting? Can you build a website presence for the event?

7. Can you identify subgroups within the populations who might be attracted to specific sessions at the conference, and ensure that such sessions are organized and promoted?

8. Can you enlist attendees who come there to earn a class or workplace credit?

Meeting Preparation:

9. Aside from having people at a registration desk, have volunteers been assigned to welcome people to the event and make sure they are comfortable and know people?

10. Can you identify a prominent person to serve as an emcee and moderator?

11. Can you provide name tags for everyone to facilitate networking?

12. Can you provide a “loot bag” of coupons or items to add to the value of coming to the event?

13. Can you offer activities or services (medical tests, 5-minute massages, information tables) that add value to the time spent at the meeting?

14. Can you arrange for a high-quality photographer to assist with promoting the meeting’s messages? Can you arrange for someone to blog about the event or its themes? Can you arrange video recording of major events?

15. Can you provide “whisper translators” for people who need language assistance at the meeting?

Meeting Curation:

16. Is there social time before and after formal sessions?

17. Does each session have adequate set-up, time, and facilities for audience members to participate? Are panelists or moderators encouraged to ask the audience to share their opinions on a specific question? Have meeting participants been coached on ways to make themselves heard and felt at meetings, as suggested here?

18. Has someone been assigned to facilitating meetings among people who will benefit from meeting one another?

19. Has someone been assigned to take notes as a “deep listener” (a term I got from Satya Ramen) who can summarize near the end of the meeting all that’s happened and been accomplished by the meeting?

20. Have people who came to the event been surveyed for their opinions?

21. Have audience members been asked to post about the event to their social media connections?

22. Has there been a call to action, and a means to stay involved with the purposes of the meeting?

23. Has a social space been organized for people who want to decompress, celebrate and chat after the meeting is over?

This is Yours Truly, closing the conference with thanks and congratulations to all, after the 5000th meeting of my life. (photo by Errol Young)

If you enjoyed this article and would like to keep up with other things I write, please subscribe to my free newsletter at bit.ly/lettersfromwayne