Ed. note: You can read Part 1 of this series on Resilience.org here.

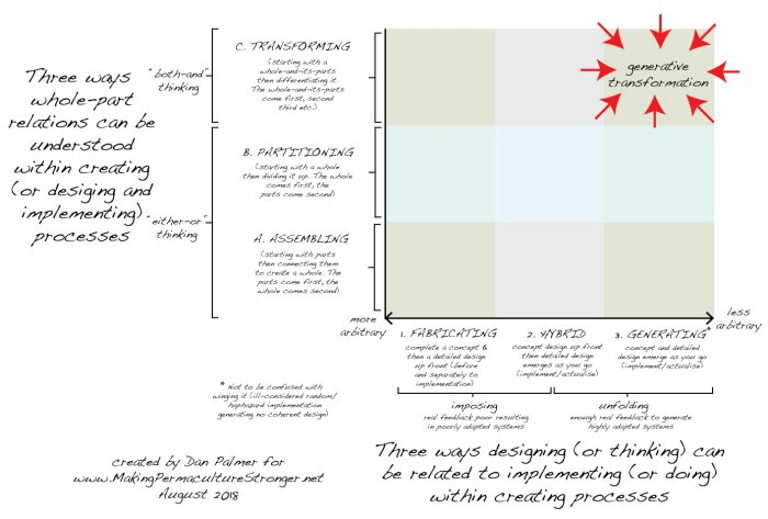

The last post introduced this weird and possibly confusing little diagram:1

The diagram frames a pathway from more conventional design processes toward what I believe permaculture is deep down really about. The conventional starting point I’m calling fabricated assembly. The radical alternative the diagram invites us toward is what I call generative transformation.

Generative transformation is really good stuff. I believe permaculture and generative transformation are meant to be together, just like orchid and wasp, legume and rhizobia, or carbon and nitrogen in the perfect compost. Indeed, I’d argue that generative transformation is in play when any permaculture project really shines.

Which leads us to a question.

WTF is Generative Transformation?

Generative transformation refers to the top-right section in the diagram.

Breaking it down, there’s the generative (or generating) piece and the transformation (or transforming) piece. Let’s start with transformation (and what it is an alternative to). We’ll come back to the meaning of generative in the next post.

Transformation

Consider the three options along the y-axis of the diagram. Starting with A. Assembling, we move to B. Partitioning, culminating in C. Transforming. I’ll here introduce and explain each as different approach to creating – as in bringing forth new form in the world.

A. Creating by Assembling

From an assembling perspective, how you go about creating (which includes both designing and implementing) is easy: choose some elements then join them into whole systems. Start with parts, stick them together and hey presto, there’s your whole!

So for example you might get a wishlist of desired elements such as pond, chook house, windbreak, and veggie patch and then figure out how to best insert and connect them to create a whole permaculture garden.

A chronic risk with this approach is that in its focus on inserting and arranging elements, it is all too easy to impose solutions (“let’s put the swale here, and then the herb spiral can go there”), even if you don’t realise that is what you are doing.

The upshot is this: When we define and apply permaculture design in this way, as we permaculturalists so widely have, what we are aiming to create, and hence what we do create is assemblages of elements.

B. Creating by Partitioning

As I showed in an early article, living systems are not assemblages of elements. Indeed, this culturally and permaculturally widespread assembly approach flies in the face of how any living organism comes into being. It was Christopher Alexander that woke me up to this fact:

Design is often thought of as a process of synthesis, a process of putting together things, a process of combination.

According to this view, a whole is created by putting together parts. The parts come first: and the form of the whole comes second.

But it is impossible to form anything which has the character of nature by adding preformed parts (Alexander, 1979, p. 368)

Alexander shows that contrary to viewing design as an assembling process, it is more accurate to say that a person’s parts or organs unfold out of the growing whole cell, embryo, foetus, where the whole comes first and the parts come second.

Taking Alexander’s words at face value, I conducted and documented several practical design examples (here is one and here another) where the whole design process was explicitly about moving from pattern toward detail and gradually partitioning the preexisting whole landscape.

So for instance you might start with an entire backyard, partition it into orchard and veggie areas, then partition the veggie area into annuals and perennials, and so on, right down to where the parsley goes.

One advantage of this approach, alongside more closely mimicking how the rest of life creates itself, is it requiring that you pay more attention to the pre-existing whole you are working with. The risk of imposing pre-formed solutions2 is thus significantly reduced. Hence it being midway on the continuum from less and more life enhancing.3

C. Creating by Transforming

Eventually, after many years designing by assembling, then having played around with designing by partitioning up the whole, the penny dropped for me. Alexander was not talking about flipping from assembling (joining parts into wholes) to partitioning (dividing wholes into parts). This is a false dichotomy. Following in Alexander’s footsteps,4 I now use the words transforming and transformation as a bigger and more inclusive process than merely assembling or partitioning.

Transformation as Seeing

Wrapped up inside what I mean by transforming is a whole different way of seeing what is, let alone doing something with it. This different way of seeing I might call deep systems thinking,5 or even a kind of field theory. I am just starting to really experience this way of seeing personally, which I believe we can all continue to get better at.6

It starts with clarity on two basic terms: whole and part. When it comes to living systems, you cannot have a part unless it is part of a whole. Similarly, there is no such thing as a whole without parts. The two words imply and need each other to make any sense.

What this means for transformation as a way of seeing is that you cannot merely start with the parts and then eventually arrive at the whole (the assembling approach). Conversely, you cannot merely start with the whole and then drill down into the parts (the partitioning approach). As much of a head f@#$ it is for the modern, linear, mechanically-oriented mind to grasp (it is perhaps easier to start by trying to experience this that than to intellectually understand it), whenever you delve into a part, you are going directly into and toward the whole. If this wasn’t true, that thing wouldn’t be a part! Likewise, whenever you are delving deeper into the whole, you are going directly into and toward the parts.7

When I observe David Holmgren reading landscape, for instance, this is exactly what I see him doing. As he reads from a small stone into the geology of the whole site, or from the lean on the trees into dominant wind patterns, he is moving toward the part and toward the whole in one and the same act.

I won’t push my luck here any further, but I would love to hear if it resonates with anyone else’s experiences and experiments and I did want to convey that there is a lot of depth in this notion of transformation even if only as an authentically holistic way of seeing.8

Transformation as Doing

When we approach what we do in this way,9 we see what we are doing as always and without exception transforming a whole-and-its-parts. To transform is to make different, to differentiate. When we are transforming a whole-and-its-parts we are making it different. No matter whether we are integrating in new parts, removing old parts, or changing existing parts around. These are all different ways of transforming the system, of differentiating the whole. Yes, it is hard to disagree, I know, and it seems blatantly obvious when I say it. But here’s the thing. Even though we might intellectually grasp and agree with this stuff, the way we then behave as designers and creators very often disagrees with it.10 As much as we might like the sound of this, it is very hard not to fall back into the culturally dominant design-by-imposing-and-assembling rut when the rubber hits the road (as Tom alludes to in this comment).

I use transformation to transcend and include the seemingly contradictory approaches of assembling and partitioning. To transform is to start, always, with a whole that already has parts. Every whole landscape already has parts. Every whole person already has parts. When we surf or dance or co-participate in the evolution of either, the whole and the parts are moving forward together, simultaneously.11

Permaculture is Transformation

Permaculture is never about starting something brand new, or with a blank slate, and dropping something entirely new into a space or place. It is always about stewarding the ongoing transformation of what is already there. In this sense, we are only ever retrofitting what we already have. For there is always, everywhere, something already going on. Which is to say there is already a whole, which already has parts. Our job is to listen to the narrative already unfolding inside any situation, then to harmonise with it and where appropriate perturb it in life-enhancing directions.

When we are in the process of practicing permaculture, furthermore, we are both tuning into and honouring aspects of the pre-existing whole situation, as well aschanging some of these aspects. What we are doing, therefore, is simultaneously conservative and creative.12 Transformation in the sense I use it here always includes both.

Tabular Recap

The following table recaps the three-way distinction between assembling, partitioning and transforming. I hope it helps and that you are getting a feel for the distinction and if and how it might shed light on how you see and work with things.

Conclusion

Hopefully this idea of transformation and how it differs from both assembling and partitioning has landed clearly. In the next post we’ll focus on the x-axis and what is meant by the progression from a fabricating through a hybrid to a fully generative approach to designing and implementing.

Meantime, if you’ve any inclination whatsoever, please do leave a comment sharing your honest impressions.

References

Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press

Bortoft, Henri. The Wholeness of Nature : Goethe’s Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature. Lindisfarne, 1996.

Endnotes

- Though I thank all those readers whose comments show they successfully deciphered it – hooray!

- from the ever-bulging and oh-so-exciting permaculture grab-bag

- It is hard to enhance life when you are unconsciously pre-committed to imposing and assembling elements on top of it!

- Or standing on his shoulders, if you prefer

- Which I contrast with shallow systems thinking which still starts with separate parts but emphasises the interactions between them or how they come together to form whole systems.Indeed, part of what I mean by transformation is a radical departure from a deeply, deeply entrenched worldview that has infected every human who has been raised within the crucible of modern civilisation.Sometimes referred to as mechanism, or reductionism, this worldview holds that the world is like a complex machine and that the way to understand it is to analyse or break it into its component parts, understand them (usually by further analysing them), then put them back together and hit the start button to understand how the interaction between the separate parts gives rise to the dynamics of the whole. Systems thinking is sometimes differentiated from reductionism by stressing its focus on the interaction between the parts rather than the separate parts themselves. While it has its role to play, I find this kind of systems thinking shallow and unsatisfying. Shallow in the sense it is a variation on the same underlying mechanistic theme. Unsatisfying like a burger that looked great on the menu but in practice is smaller, stale, cold and undercooked. I believe that when permaculturalists unwittingly adopt this shallow version of systems thinking, we do ourselves a disservice. We unwittingly impose a conceptual framework that dishonours the deep complexity of the natural systems we seek to understand and collaborate with.

- I can’t help but wonder if the experience (as opposed to all this talk) of this way of seeing is a tiny step in the direction of indigenous ways of seeing and being in place.

- Here is how Henri Bortoft (1996) has put it:“…the whole is reflected in the parts, which in turn contribute to the whole. The whole, therefore, cannot simply be the sum of the parts–i.e., the totality–because there are no parts which are independent of the whole. For the same reason, we cannot perceive the whole by ‘standing back to get an overview.’ On the contrary, because the whole is in some way reflected in the parts, it is to be encountered by going further into the parts instead of by standing back from them” (p. 6)“If we do separate whole and part into two, we appear to have an alternative of moving in a single direction, either from part to whole or from whole to part. If we start from this position, we must at least insist on moving in both directions at once, so that we have neither the the resultant whole as a sum nor the transcendental whole as a dominant authority, but the emergent whole which comes forth into its parts. …the parts are the place of the whole where it bodies forth into presence. The whole imparts itself; it is accomplished through the parts” (p. 11)

- Seriously, I’m struggling to rein myself in here, as there there is so, so much more to it, including the different way of perceiving space implicit in Alexander’s statement that”the whole gives birth to its parts: the parts appear as folds in a cloth of three dimensional space which is gradually crinkled” (1979, p. 370). All in good time, all in good time.

- For the record all seeing is doing and all doing involves seeing or at least sensing. I am drawing a distinction but they are in no way separate.

- As Alexander has put it, “there is a vast gulf between what people say they do, and what they actually do.”

- And as soon as a part stops being-part-of-a-whole, or before it becomes a part, it is actually not a part of that whole! From the perspective of the whole it is just a thing that once was or sometime might become a part of whatever whole we’re focusing on.

- These two things are often set up as mutually exclusive opposites in our culture, much like assembling and partitioning.