Daughter Skya Dietz: Caring for the Last Rhinoceroses

On a typical school night, I was relaxing in the living room in front of the TV when my mom told me the last male northern white rhino had died. The news didn’t officially register until I started talking to my dad. When I told him what had happened, I just started crying. Tears rolled down my face at the thought that an animal so well-known might go extinct right under our noses. I cried for the next half hour, sadness and fear taking over. Everything seemed so unimportant. Why was I wasting my time at school learning about ancient Japan when something like this was happening not only to rhinos but to so many animals?

The last male northern white rhino was named Sudan. He had been living in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya for nine years where he was guarded by armed caretakers around the clock. Sudan needed protection from poachers who wanted to steal his horn, which they could sell on the black market to collectors or to people who believe rhino horns have magical or medicinal powers. At 45 years old, Sudan developed a leg infection, and he could no longer stand. His caretakers euthanized him on March 19, 2018, just a couple of weeks before my thirteenth birthday.

Why did the death of Sudan upset me so much? When I had turned six, I went on a trip to San Diego. One of the memories that burns bright in my mind from that trip was visiting the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. It was exciting to see all the amazing animals at such a young age, but the thing that stood out the most was coming near the northern white rhino, Nola. The tour guide announced that Nola was one of just seven left in the entire world. That single sentence stuck with me, and I think it had an influence on how I think about people and the way we treat nature.

A few years later, a friend told me that Nola had died. I don’t remember all that well how I felt, but there was a sense of loss, and I wanted to do something to help the rhinos. I became obsessed and checked out every book about rhinos that I could find at the library, but there weren’t all that many, and reading them didn’t prepare me for what’s happening to the northern white rhinos. By the time Nola had died, there were only three left. I was appalled and horrified that people still wanted to kill an animal on the very edge of extinction. Still, rhinos slipped to the back of my mind with school and activities until the story of Sudan broke.

The day after, I was feeling depressed. When I told a close friend about Sudan, we shared feelings of despair. We couldn’t bring ourselves to do anything during PE. We just sat in the bleachers and looked so sad that our teacher came and asked if we were ok. In math class, I mostly sat with my head down on my desk resting on my arms. Being sad sucks, but it really doesn’t do anything for you. So after I had taken some time to process the news, I decided to get busy. The first thing I did was to look at the website of the World Wildlife Fund. I donated some of my birthday money to them to help protect animals and their habitats. I’m also giving thought to a career in conservation biology. My dad told me that I could write an article and he could work with me to try to get it published. So that’s what I’m doing now – writing this article. Maybe a few people will listen or find it interesting.

I hope people will feel like helping rhinos and other animals in whatever ways they can. I hope more people will take action and support organizations that are making a difference. I hope people will stop using products that cause harm, like palm oil grown on plantations that have taken over rain forests. Most of all, I hope people will care more about what we’re doing to the Earth.

Father Rob Dietz: Carrying the Weight of a Rhinoceros on Your Shoulders

My almost-13-year-old daughter recently told me, “I’m sad and depressed.” When I asked her why, through her tears, she told me that the last male northern white rhinoceros had died. Although she and I have had plenty of conversations about heavy topics like climate change and school shootings, I wasn’t prepared for this one. I stumbled, bumbled, and mumbled for a bit as I tried to check my own emotions. What 12-year-old should have to carry the burden of humanity’s mistreatment of the planet? And why should her father have to explain that she’s right to feel sad and depressed?

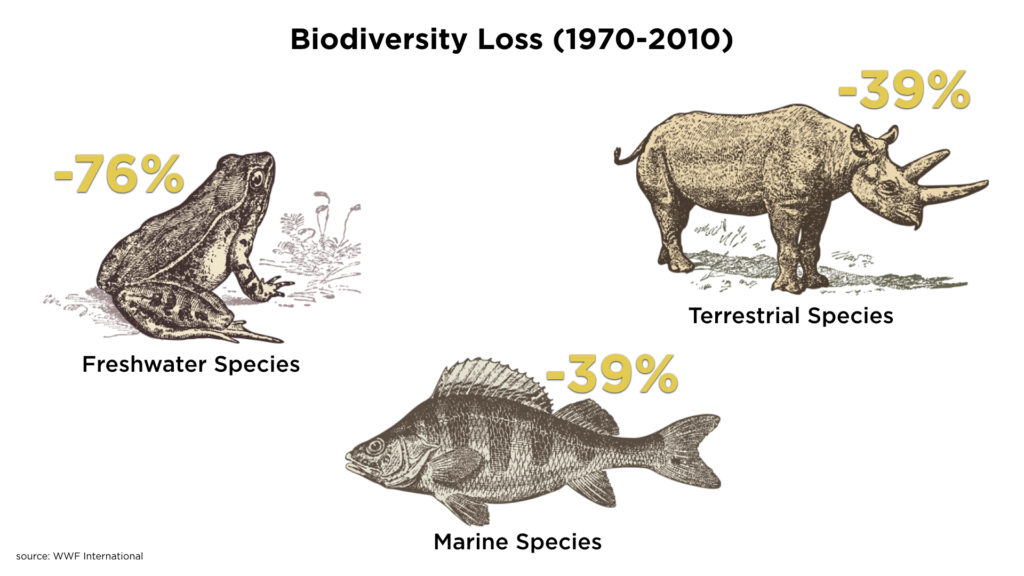

Anyone with even a passing interest in wild places and wild creatures shouldn’t be the slightest surprised by the rhino’s descent toward extinction. Conservation biologists have been documenting for decades the effects of habitat loss, ecosystem degradation, species overharvesting, and pollution on rhinos and countless other living organisms. Just a few months ago, scientists published a study that found a 75% decline in flying insect populations in German natural areas over a 27-year period. Although the findings were reported by news outlets, they didn’t seem to cause much of a stir, at least in North America. It has taken just one generation to pummel a population of creatures that have survived and contributed to food webs and ecosystems for eons.

The trouble is that not enough people take a passing interest in wild places and wild creatures. And many of us who do fail to address or consider the root cause of the problem: there are too many people consuming too many resources. Continuous economic growth around the globe is incompatible with conserving the diversity and complexity of Earth’s ecosystems and organisms. The more we transform nature into pavement, Walmarts, monocrop farms, plastic trinkets, and other trappings of the consumerist mindset, the more we undermine the life-support systems of the planet. Our predicament is that we need to do things very differently. We need to change our behavior, change our lifestyles, and change the entire economy, but there’s incredible resistance to change.

Back to my daughter’s lament. Her sadness about the rhino dragged her down a pretty dark hole. She questioned the point of trying in school. Why waste time and paper answering questions in history class when all of us ought to be working to prevent runaway climate change, conserve remaining intact ecosystems, and restore damaged lands and waters? She asked if it was all pointless. I’ve been struggling with similar questions for much of my adult life, but at least I’m a grownup – sheesh!

Once I regained my footing in our conversation, I told her that her feelings were totally valid. It’s ok to be sad and angry. The trick is to find a way to process those emotions and then do something useful. You want to avoid allowing the emotions to overwhelm you and demotivate you – that’s the start of a downward spiral into cynicism and depression. You may not be able to change the world; you may feel powerless – there’s no magic wand to wave that’ll bring back healthy ecosystems and the species we’ve killed off, but you never know how much your words and actions can help. With apologies to Tennyson, ‘tis better to have tried and failed than never to have tried at all.

She then asked, “What can I do?” We came up with a few ideas. One of which was to share her story. Maybe describing how she feels can inspire others to do some thinking and take some actions. I’m helping her write about her reaction to the rhino’s death, and I decided to write this article. She has already donated some of her spending money to a wildlife conservation organization. She and her friend also baked a bunch of muffins and handed them out to people living on the streets. Sharing food with people who live less secure lives may seem unrelated to the biodiversity crisis, but there’s a congruence between caring for one another and caring for our home. Acting with kindness and empathy is the key to recovering what we can of what’s being lost, and the key to moving forward as stewards rather than exploiters. I’m proud of my daughter’s response. But I’m still fuming about what she and her peers are facing.

Teaser photo credit: By Lengai101 – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10826693