New research provides strong evidence that one of the long-predicted worst-case impacts of climate change — a severe slow-down of the Gulf Stream system — has already started.

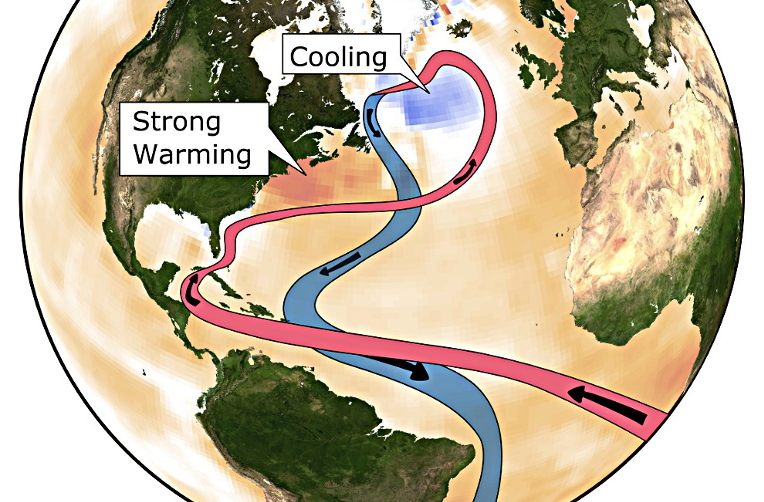

The system, also known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), brings warmer water northward while pumping cooler water southward.

“I think we’re close to a tipping point,” climatologist Michael Mann told ThinkProgress in an email. The AMOC slow down “is without precedent” in more than a millennium he said, adding, “It’s happening about a century ahead of schedule relative to what the models predict.”

The impacts of such a slowdown include much faster sea level rise — and much warmer sea surface temperatures — for much of the U.S. East Coast. Both of those effects are already being observed and together they make devastating storm surges of the kind we saw with Superstorm Sandy far more likely.

The findings come in two new studies published this week. One study published in the journal Nature, titled “Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation,” was led by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. It finds that the AMOC has weakened “around 15 per cent” since the mid-twentieth century, bringing it to “a new record low.”

Another new study in the same issue of Nature “supports this finding and places it in a longer climate history context,” as Potsdam’s Stefan Rahmstorf notes at RealClimate.

A video from Potsdam Institute explains how we know the slowdown is being driven by human-caused climate change: The observed fingerprint of temperature changes in the Atlantic are precisely what the models predicted would happen when the slowdown began in earnest.

The impacts are serious. A slow-down in deepwater ocean circulation “would accelerate sea level rise off the northeastern United States, while a full collapse could result in as much as approximately 1.6 feet of regional sea level rise,” as the authors of the U.S. National Climate Assessment (NCA) explained in November.

This extra rise in East Coast sea levels would be on top of whatever multi-foot sea level rise the entire world sees. An AMOC slowdown would reduce regional warming a bit, especially in Europe, but “would also lead to a reduction of ocean carbon dioxide uptake, and thus an acceleration of global-scale warming.”

And the slowdown also means a rise in water temperatures off the U.S. mid-Atlantic and Northeast coasts, which has already begun (see map).

So this new research on the AMOC slowdown provides evidence that human-caused global warming is responsible for a much larger fraction of the higher East Coast SSTs (and sea level rise) that fueled the super-charged storm surge of Sandy than previously thought.

As Dr. Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University’s Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences explained back in 2013:

“Abnormally high sea-surface temperatures all along the eastern seaboard at the time, which must have some component associated with globally warming oceans, likely helped Sandy maintain tropical characteristics longer and allowed the storm to travel farther northward than would be expected in late October. Warmer ocean waters would also increase evaporation rates, adding to the moisture and latent heat available to the storm.”

The key question has always been what fraction of the recent rise in eastern seaboard SSTs (and sea level rise) can be attributed to global warming. Increasingly, it seems that a very large fraction can.

So it appears likely that catastrophic East Coast flooding will get much worse, much faster than anyone had expected.