From the Transition Network blog: This is the first blog from guest editor, Wangũi Kamonji.

My mum loves taking photos. To commemorate that she was in a certain place and who she was with, each photo fanning out into a story that can be told to relatives and friends who were not present. One thing about her photo taking has always amused me: her insistence on having something ‘green’ in the photo be it tree branches, leaves, even a blade of grass hastily broken off and held. When I ask her why, she says: “For the photo to look good”. To have beauty in it, a picture isn’t complete without her holding or being next to some piece of nature.

If I were to ask a non-African what comes to mind when they hear ‘African environment’, the highest chance would be wild animals. Second may be tree planting. Wildlife conservation and tree planting are both worthy causes. They are also contested arenas for the political and ecological issues they bring up, such as choice of species, land displacement of indigenous peoples, and conversion of biospheres that supported diverse functions into mono-functional ecologies.

These two issues might also be the extent of what many Africans, who have over years of external and internalised oppression become separated from their environments, think encompasses environmental concern. From being our first classrooms, we are now increasingly divorced from land hence less and less environmentally conscious.

I want to explore an African view of the environment born of Africans in their environments in this series. I am interested in broadening our imagination of what African environmentalism is.

I just completed Ramachandra Guha’s book ‘Environmentalism – A Global History’, a valiant effort that traced the birth, growth and changes of the ‘global environmental movement’. Tucked at the back in the bibliographical essay was one line on environmentalism in Africa: “There are, as yet, no authoritative works on African environmental conflicts…”

This sentence presents a number of issues for how and why we imagine (or don’t) an African environmentalism. One is where it locates the origin of the environmental movement; another the summative description of environmentalism as conflict; third the easy dismissal of the existence of environmentalism in Africa; and finally the notion of “authoritative works” and the perception that only these can be a source of knowledge on African environments.

Environmentalism, according to Guha, is a reaction to environmental threat and its birth is traced to the industrial revolution. It is true that the industrial revolutions, and neoliberal capitalism following it have forced innovation in the ways that people protect and maintain livelihoods and environments. But I think it is short-sighted, risky and possibly racist to locate the origin of care for the environment in the 19th century. In doing so we lose sight of the wealth of years of environmental engagement before the industrial revolution and of those who performed it which makes it easy to lose sight of those people today too.

One of the reasons conservation in Africa is contested is that the prevailing discourse of saving the wild from the Africans doesn’t stop to consider that the reason there is something to conserve is thanks to those same Africans. It is forgotten that national parks in many African nations were started as hunting grounds for white men eager to prove their manhood, (including US president Teddy Roosevelt), and in their creation, herders who contributed to creating and maintaining those ecosystems were forcibly removed. Efforts at squeezing productivity from colonies and taming wild Africa(ns) had innumerable ecological effects, converting natural forest into mono-stands of wattle and river-drying eucalyptus plantations, and introducing monocrop cocoa wheat, coffee, and tea among other export crops whose productivity is tied to harmful pesticides and fertilisers for example. Post-independence, the pressure to accumulate foreign exchange in a market stacked against agricultural commodities intensifies and keeps this cycle going.

The costs of (the false promise of) endless growth are largely borne by those whose livelihoods depend on their environments. In response, people world over have asserted their visions for and rights to their environments, and the rights of the environment, in new ways. It is true, the threats we face today are more sinister, invisible, and operate at multiple levels. But our responses must be seen as a continuation of environmental thought and practice, not a break from, or separate. The environmentalism of today stands on the shoulders of the centuries we have been on this earth negotiating (with) our environments.

Locating environmentalism as beginning after industrialisation risks beginning the story the wrong way round as Adichie cautions in her Ted Talk.

But is it environmentalism that what we conserve wouldn’t have existed if Africans hadn’t existed? They didn’t have anything to protect from so it can’t be environmentalism right? According to an environmentalism that is only against something, sure. If we define environmentalism as only against, we remain blind to the creative and maintenance work which now threatened gives us something to be against. It wasn’t just there. Humans have been involved with nature, forming and being formed, all through our existence. Indeed we ARE nature much as the post-Enlightenment world has tried to separate and distance humans from nature. (The Nature Culture divide).

I will pause here for a moment. I am speaking to fellow peoples of African descent and I have to acknowledge that the assertion that we are nature is a potentially painful and complicated one to contend with and with reason. The idea that Africans are “closer to nature” and more primitive is a racist narrative built on a flawed assumption of linear progression and degrees of civilisation. It has been and continues to be used to assert that Africans and Africa are further behind in an inevitable progression away from nature towards civilisation. In this way it is used to discount our humanity and to excuse a myriad of evils performed on Africans.

Calling that bluff I want to restore this idea to what is the reality of life. We are nature. All of us.

So why is it so easy to dismiss African environmentalism?

I think a few misconceptions are responsible.

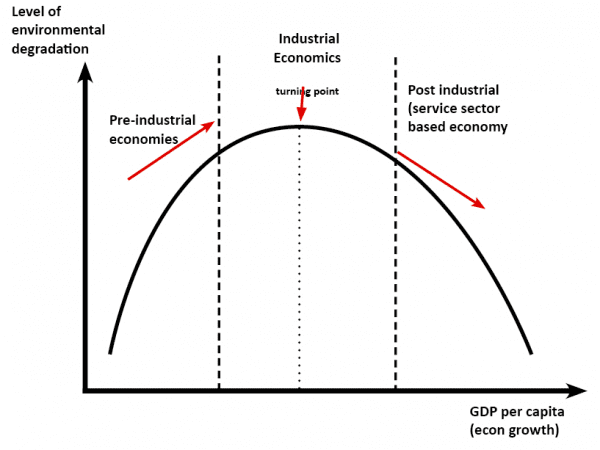

Plotting a theoretical relationship between affluence and better environments the Environmental Kuznet’s curve represents 2 misconceptions: Africans are too poor to care for the environment (yet). The graph theorises that once a population achieves ‘affluence’ their environmental concern switch flicks on. Besides the fact that this relationship does not correspond to most data on improved environmental issues, there isn’t a causal relationship between increasing wealth and environmental concern. Examples abound of people considered poor caring for and protecting their environments. The bias that environmental concern cannot exist without monetary affluence causes people to dismiss African environmentalism as impossible since affluence as measured by UN indices is found to be absent in African countries.

The second misconception is that some measure of environmental degradation and disregard is simply okay because once affluence is reached then society will clean up its mess. This plays into an economy vs environment debate that argues that there cannot be economic development within environmental limits. Ergo, Africans cannot care about their environments because the need for money and other measures of economic development are too great. This argument only holds if one’s understanding of what economic development is and can be is bound to a neoliberal capitalist model where the more you take from the earth, the faster you produce, and the more you consume the better your economy is. This model doesn’t like the idea of limits. It’s a kind of development that many activists have denounced as being development only for the few. When Wangari Maathai mobilised women to plant trees, write protest letters to the World Bank and physically occupy Uhuru Park, a public green space in Nairobi, Kenya where a skyscraper was to be built by the president she was saying, this isn’t development to us.

Third are the implicit biases enabled by racism. Africans will not react when their environments are under threat because they are too ignorant, they will not make the connections, and anyway they are distracted by the various other issues on their plates. The misconception here is that Africans are not agents of their histories and environments and do not think of the environment as something to be concerned about. Lawrence Summers, former World Bank chief economist was thinking in this way when he recommended the exporting of toxic waste to Africa because “countries in Africa are vastly under-polluted” and it made economic sense for pollution producing countries to spread their dirt (but not their wealth). Similarly, China is on the one hand closing down Chinese coal power plants and switching to renewable energy while investing in coal power plants in Africa.

The fourth reason African environmentalism is easily dismissed was in Guha’s sentence: there are no “authoritative works” about Africans caring about their environments, therefore there is no such care on the continent. African environmentalism just doesn’t exist if we don’t hear about it. The only issue is that the listener in these cases is often not an African. The one judging what is authoritative is not an African. The gaze from which such pronouncements are made are not African eyes. The notion of “authoritative works” that are the only possible source of knowledge regarding African environments discounts the Africans who live in these environments as authorities on their own lives.

Ultimately, these four misconceptions do not exist independent of each other.

The reality is far from them. African environmentalism is there and has been there. It is varied across space: existing in rural areas and in urban spaces, offshore and on islands, in forests, at the edge of deserts, in townships and informal settlements. It has taken diverse forms through the decades and centuries. Across the continent a mix of methods are employed: protest, policy, art, direct action, marches, education, prayer, academic and non-academic writing, music, performance, social media activism, presence and daily maintenance and creative work.

Some examples:

Through art, Effat Naghi bore witness to the costs of ‘development’ in the form of loss of land, accumulated cultural memory and the wealth of Egyptian Nubians due to the Aswan High Dam in Egypt.

In Venda, South Africa, Mphatheleni Makaulule and the organisation Dzomo la Mupo successfully took on the traditional authority who wanted to “develop” part of a sacred waterfall into a tourist chalet.

Residents of an informal settlement in Kenya led by mother Phyllis Omido sustained a campaign for 7 years to get a poisonous car battery recycling factory shut down.

Ken Saro-Wiwa, a poet and novelist, and the Ogoni 8 were murdered by the Nigerian government for protesting Shell and BP’s oil spills that made life untenable in the Niger Delta.

Gule wa Mkulu dancers from Mua in central Malawi have created plays and films using the rich repertoire of characters from the dance to give voice to the issues of plastic waste and deforestation.

The community of Grassy Park in South Africa used participatory design, community clean-ups, storytelling and mythmaking, and legal action to win a campaign to preserve and develop a wetland close to them according to a community vision rather than have a mall built on the land.

The New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, a G8 initiative in partnership with the World Bank and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is requiring introduction of a law criminalising long-standing farmer to farmer seed exchange in Tanzania under threat of withdrawing aid. Janet Maro and the national organic movement are working to have this law thrown out.

An on-going struggle to preserve the World Heritage Site of Lamu Island where a coal power plant is due to be built has taken the form of public debate fora, art exhibitions, a court case and social media activism to denounce the preference for non-local investment and benefits for a few elite, over resident voices and livelihoods.

To reach back and forth through the centuries, hunting among different San groups were accompanied by prayer and ritual. An animal was thanked for agreeing to die to feed humans. Similarly, among the livestock keeping communities in Kenya that maintain their traditions, an animal to be slaughtered has to ‘agree’, otherwise a different one must be selected.

I invite you to see with new eyes. Ultimately Guha’s definition of environmentalism is not wrong. It just doesn’t fit mine and many others’ reality of what environmentalism is: holistic; long rooted in time and space; for something and not only against; alive and based in the land, lives, work and bodies of those around me, African in and of their environments.

In the coming months I offer some less known home-grown stories from Kenya of what care for the environment as ecology, society, economics, material and immaterial realities can mean. Stories from people working to give environmental consciousness life and form today. Like my mum who reminds me she is (connected to) nature every time she takes a photo. Ultimately these are our stories. May we see ourselves.