For years, environmental justice advocates have been saying that it’s time to shift the focus of the environmental movement from beautiful landscapes and big animals to the people choking on black carbon or poisoned by lead in their water.

Now, some of those people who grew up in dumping grounds have come into power and are shaping politics on the world stage. And when California sent a delegation to the U.N. climate conference in Bonn a few weeks ago, it was packed with members of the movement, including state Senator Ricardo Lara.

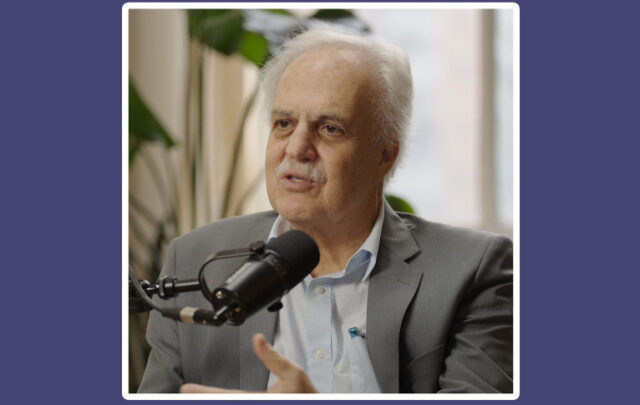

Lara grew up downwind of burning carcasses and diesel exhaust in Los Angeles. In his seven years in the California Legislature, he’s helped pass several laws to cleanup pollution and cut greenhouse gases. Lara sees himself as a champion for the environment as a whole, not just for environmental justice. The environmental justice goal of combating the health effects of living with pollution is increasingly shared throughout the environmental movement.

Grist recently spoke with Lara about his childhood playing baseball in the cinders of a railyard, his reasons for focusing on sickness and death rather than the abstract “environment,” and why we should all start “waving the super-pollutant flag.”

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. I wanted to talk to you because you were at Bonn representing California, and you were really changing the conversation by talking about people who are suffering rather than polar bears.

A. Well, first of all, polar bears are important. But the whole conversation in Bonn was about how to keep the temperature from rising 2 degrees Celsius. What does that mean to people back home? Absolutely nothing.

So I was having conversations with scientists about alternative metrics that mean something to people. How do we go to farmers and talk about the percentage of farmland that will be destroyed? How do we go to L.A. and talk about what will happen in asthma clusters, cancer clusters, low birthweight areas? How do we present metrics in terms of property loss or potential to save people’s property? Can we at least start the research to quantify the impacts not just on polar bears, but on the daily lives of people?

Q. Are you saying that most people would just shrug at the goal of preventing warming — but if we talk about deaths, or taxes to build seawalls, people understand why that’s important?

A. Exactly. Those are tangible things we can take to businesses and community advocates.

Q. When did you start caring about the environment?

A. I grew up in an industrial hub of southeast Los Angeles County between two freeways. Talk about “ignorance is bliss:” I grew up playing baseball in a rail yard and in the parking lots of these big companies because that was the only open space we had. Certain days of the week my mom would say, “Don’t forget to shut the window because the smell is going to come.” You would smell the emissions, you would smell the Farmer John’s meat processing plant where they were burning carcasses. It was just our way of life.

It wasn’t until I went to school in San Diego that I went, “Whoa, people have nice parks! People don’t have to shut their windows during the week.” When I came home I thought, “We are really screwed here.”

So as a legislator, I go to Sacramento and try to engage on the environment. But the environmental movement didn’t look like me and wasn’t addressing these issues. So I decided early on that I was going to take my time to understand and then inject myself into the conversation, rather than waiting for permission. And rather than just working on the environmental justice part of it, I wanted to work on environmental issues as a whole, bringing in my environmental justice perspective into the heart and soul of the policies.

Q. I’ve talked to environmental justice advocates who say legislators — even legislators who come out of poorer, polluted communities — aren’t doing enough, and making too many compromises with industry.

A. I appreciate the advocates. They play a vital role. As a policy maker, my job is to try and find solutions that are going to allow us to clean up these communities. Although nothing is perfect, we’re now making the largest single investment in California history to clean up car and truck pollution, with close to a billion dollars.

That directly impacts my community because I represent the most important transportation corridor in the country — the [Interstate] 710 to the ports of Long Beach and L.A. About 40 percent of the goods from the Pacific Rim come through those two ports. That’s an enormous economic benefit, but it has decimated communities. So that nearly $1 billion to create cleaner, more efficient trucks is going to save lives in my community.

The advocates keep us on task, but we need to engage with industry so they can be part of the solution as well.

Q. Can you talk about the work you’re doing on so-called super pollutants, like hydrofluorocarbons? They’re some of the most important contributors to climate change but hardly anyone knows about them.

A. I know, right? It’s like me and my staff waving the super-pollutant flag and everyone is like, wha?

They are often called “short-lived climate pollutants” — but that doesn’t sound threatening enough. What’s why we called our bill the “super-pollutant reduction act of 2016.” That law will now restrict gases from refrigerants along with methane and soot. We’re also working on a bill that would use California’s economic prowess to get industries to cut fluorinated gases — another a super pollutant — if a pending court decision eliminates federal regulation.

Q. Anything else you’d like to mention that has you excited?

A. I’m excited that we were able to clearly say in Bonn that California is still in the Paris climate agreement. And that California’s environmental movement really looks like California. It’s being directed and championed by people who come from low-income communities. That’s long overdue, and it’s only going to make us more powerful.