The organic food movement suffered a major setback recently, when the US National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) voted in favor of allowing hydroponically-grown products to receive the “organic” label. This decision should not have come as a surprise to those who have watched the organic movement steadily taken over by big agribusiness – a process that began in 1990 when Congress required the USDA to create a single set of national standards that would define the meaning of “organic”.

Previously, “organic” meant striving for a healthy relationship among farmers, farm animals, consumers, and the natural world – with soil-building seen as central to the long-term health of agriculture. Organic farms were certified by statewide or regional organizations using locally-defined standards, with the understanding that food production was necessarily diverse – reflecting local climates, soils, wildlife, pests, and so on. A one-size-fits-all national standard wasn’t needed to protect consumers who purchased food from local or regional organic farms, but it was required if global trade in organic products was to expand. The all-but-inevitable result has been a takeover of the organic market by corporate agribusinesses, along with a steady watering down of the standards – which have been largely reduced to a list of proscribed chemicals and required practices meant to apply everywhere. (At Local Futures we continue to believe that localizing food production offers the best way for consumers to know how their food was produced.)

After the decision to allow hydroponics under the “organic” label, National Organics Standards Board member Francis Thicke delivered the following farewell message to the Board:

There are two important things that I have learned during my five years on the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB). First, I learned that the NOSB review process for materials petitioned for inclusion on the National List is quite rigorous, with Technical Reviews of petitioned materials and careful scrutiny by both NOSB subcommittees and the full board.

The second thing I learned, over time, is that industry has an outsized and growing influence on USDA – and on the NOSB (including through NOSB appointments) – compared to the influence of organic farmers, who started this organic farming movement. Perhaps that is not surprising, given the growing value of organic sales. With organic becoming a $50 billion business, industry not only wants a bigger piece of the pie, they seem to want the whole pie.

We now have “organic” chicken CAFOs [concentrated animal feeding operations] with 200,000 birds crammed into a building with no real access to the outdoors, and a chicken industry working behind the scenes to make sure that the animal welfare standards – weak as they are – never see the light of day, just like their chickens. The image consumers have of organic chickens ranging outside has been relegated to pictures on egg cartons.

We have “organic” dairy CAFOs with 15,000 cows in a feedlot in a desert, with compelling evidence by an investigative reporter that the CAFO is not meeting the grazing rule – not by a long shot. But when USDA does its obligatory “investigation,” instead of a surprise visit to the facility, USDA gives them a heads up by making an appointment, so the CAFO can move cows from feedlots to pasture on the day of inspection. This gives a green light to that dairy CAFO owner to move forward with its plans to establish a 30,000-cow facility in the Midwest.

We have large grain shipments coming into the US that are being sold as organic but that lack organic documentation. Some shipments have been proven to be fraudulent. The USDA has been slow to take action to stop this, and organic grain farmers in the US are suffering financially as a result.

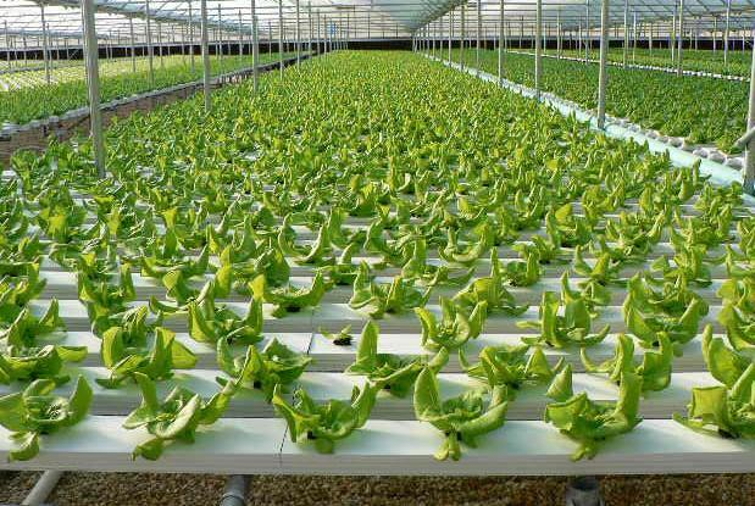

We have a rapidly growing percentage of the fruits and vegetables on grocery store shelves being produced hydroponically, without soil, and mostly in huge industrial-scale facilities. And we have a hydroponics industry that has deceptively renamed hydroponic production – even with 100% liquid feeding – as “container” production. With their clever deception they have been able to bamboozle even the majority of NOSB members into complicity with their goal of taking over the organic fruit and vegetable market with their hydroponic products.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to find that big business is taking over the USDA organic program, because the influence of money is corroding all levels of our government. At this point, I can see only one way to bring the organic label back in line with the original vision of organic farmers and consumers. We need an add-on organic label for organic farmers who are willing to meet the expectations of discerning consumers who are demanding real organic food.

A while back I wouldn’t have supported the idea of an add-on organic label because I, like many others, saw the USDA organic label as the gold standard, and hoped that through our vision of the process of continuous improvement we could really make it into that gold standard. Now I can see that the influence of big business is not going to let that happen. The USDA is increasingly exerting control over the NOSB, and big business is tightening its grip on the USDA and Congress. Recently industry representatives have publicly called on the US Senate to weaken the NOSB and give industry a stronger role in the National Organic Program. And sympathetic Senators have promised to do just that.

I now support the establishment of an add-on organic label that will enable real organic farmers and discerning organic consumers to support one another through a label that represents real organic food. I support the creation of a label, such as the proposed Regenerative Organic Certification, that will ensure organic integrity; for example, that animals have real access to the outdoors to be able to express their natural behaviors, and that food is grown in soil. My hopes are that this add-on certification can be seamlessly integrated with the NOP certification, so that a single farm organic system plan and inspection can serve to verify both NOP and the higher level organic certification, by certifiers that are accredited by both certification systems.

I also am pleased that organic farmers have recently organized themselves into the Organic Farmers Association (OFA), to better represent themselves in the arena of public policy. Too often in the past the interests of big business have overruled the interests of organic farmers – and consumers – when organic policies are being established in Washington. I hope this will allow organic farmers to gain equal footing with industry on issues that affect the organic community.

In summary, organic is at a crossroads. Either we can continue to allow industry interests to bend and dilute the organic rules to their benefit, or organic farmers – working with organic consumers – can step up and take action to ensure organic integrity into the future.