Naomi Klein’s new books always provoke plenty of excitement on the left. For starters, they always seem to augur new waves of popular struggle. The Canadian journalist’s debut No Logo, an exposé of corporate super-branding, went to print with prophetic timing just months after the 1999 Seattle protest kicked off the alter-globalisation movement. Her 2007 follow up The Shock Doctrine, on how elites use crises to push through neoliberal policy, pre-empted the credit crunch. And This Changes Everything, on the clash between free-market fundamentalism and climate justice, was published during the tense build-up to the COP21 climate talks. Each book in this anti-neoliberal trilogy became a left-wing manifesto of sorts, making sense of pivotal moments in the movements and capturing the prevailing dissident mood.

Naomi Klein’s new books always provoke plenty of excitement on the left. For starters, they always seem to augur new waves of popular struggle. The Canadian journalist’s debut No Logo, an exposé of corporate super-branding, went to print with prophetic timing just months after the 1999 Seattle protest kicked off the alter-globalisation movement. Her 2007 follow up The Shock Doctrine, on how elites use crises to push through neoliberal policy, pre-empted the credit crunch. And This Changes Everything, on the clash between free-market fundamentalism and climate justice, was published during the tense build-up to the COP21 climate talks. Each book in this anti-neoliberal trilogy became a left-wing manifesto of sorts, making sense of pivotal moments in the movements and capturing the prevailing dissident mood.

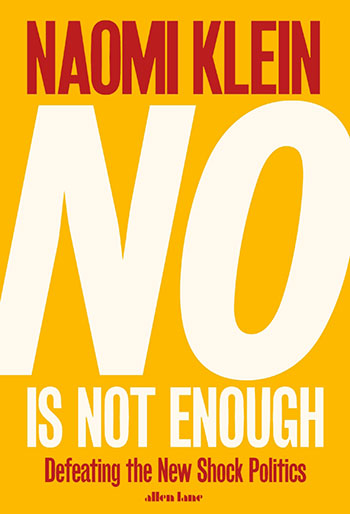

Klein’s latest book No Is Not Enough, on the rise of Trumpism, comes at another pivotal (perhaps epochal) moment. But unlike her previous books, each of which took years to write, she wrote No Is Not Enough in a few months. This rapid turnaround was for a couple of reasons. First, due to necessity – Trump’s shock win required urgent analysis. And second, because this time she hasn’t sought to break new ground – for Klein, Trump embodies the worst excesses of the neoliberal phenomena she already covered in her first three books. She writes: ‘Trump is not a rupture at all, but rather the culmination – the logical end point – of a great many dangerous stories our culture has been telling for a very long time.’ So No Is Not Enough mainly revisits and ties together threads from her earlier canon. Much of the book is taken up describing Trump the ultimate super-brand, Trump the doctor of shock therapy, and Trump the climate vandal – as well as, of course, Trump the sexist and racist.

Clearly there are continuities between mainstay neoliberalism and Trump’s regime, and Klein provides plenty of material making the link. I do think her framing is somewhat misleading, however. Far from Trump being the apotheosis of neoliberalism, his rise is a morbid symptom of neoliberalism’s deep, intractable crisis beginning in 2008. Its nostra are increasingly ineffective. People across the political spectrum now talk of its foreseeable demise.

If the left doesn’t get its act together, the danger is that the rise of Trumpism threatens to turn into something qualitatively different – fascism. Klein acknowledges the risk. For example, in chapter 5 she says: ‘White supremacist and fascist movements – though they may always burn in the background – are far more likely to turn into wildfires during periods of sustained economic hardship and national decline.’ And: ‘We are allowing conditions eerily similar to those in the 1930s to be re‑created today.’

But these passages are relatively cursory and leave the impression that the encroachment of fascism is somewhat abstract, rather than a process presently unfolding in the movement around Trump and beyond. What’s going on around the world right now is not business as usual.

For me, the most forceful part of No Is Not Enough is in chapter 4, ‘The climate clock strikes midnight’, where Klein reprises her arguments from This Changes Everything. The reason conservatives deny climate change, she argues, is that they realise climate action necessitates collective struggle that would bring down the entire neoliberal system. The huge public investment, job creation, regulation, higher taxes and so on required to save the climate are simply not compatible with the current phase of capitalism.

Klein explains climate denial thus: ‘In short, climate change detonates the ideological scaffolding on which contemporary conservatism stands. To admit that the climate crisis is real is to admit the end of the neoliberal project.’

However, as in her previous works, Klein stops short of calling for full-blown system change. Instead her long-term strategy seems to involve a radical form of social democracy in which markets still exist but are tempered by enlightened regulation.

In the closing chapters, she describes her role in developing the Canadian ‘Leap Manifesto’, which involved bringing together a range of marginalised communities to draft a vision document that opposes austerity and promotes both the rights of peoples and climate justice. There is nothing to disagree with in the manifesto, except to question how we can achieve such radical demands while confined within the logic of the markets.

Despite my various friendly critiques here, it goes without saying that Naomi Klein is one of the most important figures on the radical left today. There are few other activists who are able to make radical arguments that are read by so many and taken seriously in the mainstream. The first thing I ever read on neoliberalism was Shock Doctrine, and although I have now departed from some of her arguments, it was a wake‑up call and instilled in me a sense of righteous anger that persists today. For those who want to fight injustice, a good place to start is to read Naomi Klein.

Teaser photo credit: Kourosh Keshiri