New York Magazine has stirred up a firestorm of debate by publishing a worst-case scenario for climate change this week, “The Uninhabitable Earth” by David Wallace-Wells.

Responses range from Mashable’s “Do not accept New York Mag’s climate change doomsday scenario,” to climatologist Michael Mann’s critical Facebook post, to Slate’s “New York Magazine’s global-warming horror story isn’t too scary. It’s not scary enough.”

The debate hinges on whether the piece goes too far in scaring people about the worst possible effects of climate change, or is justified considering the stakes. Since Wallace-Wells quotes my recent primer Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know — and since I have long maintained that plausible worst-case climate scenarios deserve vastly more attention than they receive — I will share my thoughts.

What’s clear from the article and the wave of reactions it triggered is that we need to be talking a lot more about climate change in general, and why this country in particular has embraced policies and politicians that — if they continue to prevail — will destroy America and modern civilization as we have come to know it.

The first point to be made is that if you aren’t hair-on-fire alarmed about climate change and America’s suicidal GOP-driven climate and energy policies, then you are uninformed (or misinformed).

“It may seem impossible to imagine that a technologically advanced society could choose, in essence, to destroy itself,” as Elizabeth Kolbert wrote way back in 2005 in a New Yorker series every bit as alarming as the NY Magazine piece, “but that is what we are now in the process of doing.”

We have been choosing to destroy ourselves for quite some time now. Climate silence and climate ignorance are literally destroying us.

Compounding the tragedy is that now a host of core climate solutions are affordable, practical, and scalable. If there is one critique of the NY Magazine piece that sticks, it is that Wallace-Wells fails to explain clearly that we are not doomed. We are simply choosing to be doomed.

We are the “This is fine” dog.

So, to be clear, we are not doomed. If the nation and the world were to adopt a WWII-scale effort, we could certainly keep total global warming “well below 2°C” (3.6°F), which scientists — and the nations of the world — recognize as the threshold beyond which climate change rapidly moves from dangerous to catastrophic.

I have tried to be as clear as possible in my writing that we are in the midst of a game-changing, unstoppable clean energy revolution. In just the last three years, the energy world has been turned upside down by stunning price drops in solar energy, wind power, batteries and electric cars.

We need a global effort led by all of the big emitters, including the U.S., to scale up clean energy at 10 times the current rate. And, at the same time, we need all of the big emitters, including the U.S., to steadily reduce our use of fossil fuels to zero over the next half-century or so.

While one political party is clearly prepared to do this, the party that currently controls all branches of government not only opposes such policies vigorously, it publicly rejects even the most basic climate science and supports Trump’s self-destructive abandonment of the Paris climate deal.

But, again, under the current set of CO2 targets for 2025 or 2030 adopted by the world’s nations in Paris in 2015, total warming would still be 3.5°C. All of the world’s major emitters — including us — must keep coming back to the table every few years to keep ratcheting down emissions to zero as soon as possible to limit total warming to anything close to 2°C.

As long as this country is in the hands of people like President Donald Trump and the current Republican establishment, however, the world is certain to blow past 2°C and even 3°C. After all, pulling out of the Paris agreement already appears to have started a domino effect, with Turkey using Trump’s exit as an excuse to do the same and other countries, like Russia, likely to follow suit.

What is the plausible worst-case scenario for climate change this century?

Thus, the question remains: what is a plausible worst-case scenario for climate change this century?

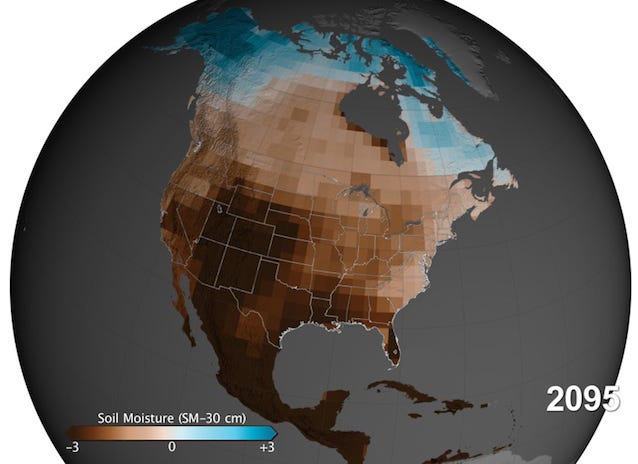

Here’s a 2015 NASA projection of what the normal climate of North America will look like on our current emissions path. The darkest areas have soil moisture comparable to that seen during the 1930s Dust Bowl.

CREDIT: NASA

This is not the worst-case scenario. It’s really much closer to business as usual under GOP climate policies. Imagine a severe megadrought lasting decades hitting both the California breadbasket and the Midwest breadbasket at the same time. That’s getting closer to a worst-case scenario in terms of drought for just this country.

Also, much of the population of Mexico and Central America — likely over 100 million people (Mexico alone is projected to have a population of 150 million in 2050) — will be trying to find a place to live that isn’t anywhere near as hot and dry, that has enough fresh water and food to go around. They aren’t going to be looking south.

A couple million Syrian refugees has turned global politics upside-down in recent years. What happens when that is multiplied 10-fold? Or 50-fold?

What makes the worst-case scenario so difficult to imagine is that it involves multiple ever-worsening catastrophic impacts happening everywhere in the world at the same time — impacts that are irreversible for centuries.

For instance, at the same time you get Dust-Bowlification in North America and so many bread baskets around the world, you also get devastating sea-level rise and storm surge.

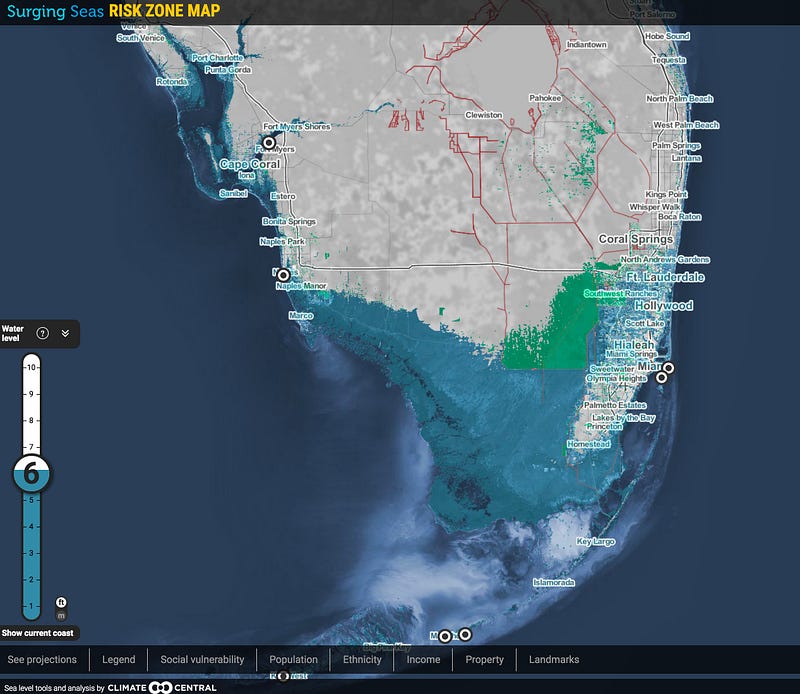

Trump policies make this future for South Florida and “Miami Island” all but unstoppable. CREDIT: Climate Central

Trump policies make this future for South Florida and “Miami Island” all but unstoppable. CREDIT: Climate Central

Again, that’s just a plausible worst case for sea level in South Florida. It’s going to be happening everywhere all at once.

One result is Superstorm-Sandy level storm surges every other year by the end of the century in the Northeast, according to 2013 NOAA study. And when Sandy-level storm surges become the norm, how bad is the worst-case scenario storm surge?

Where is everyone going to live? Where are all the refugees going to go?

The true worst-case scenario is so bad that scientists simply assume humanity is too rational and moral to let that happen.

That’s a key reason the overwhelming majority of scientific research on climate change is not about the worst-case scenario. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its more than one-quarter century of existence, has never plainly laid out what that worst-case scenario is and what it would mean for human society. However, its most recent review of the scientific literature gave an upper range for the business-as-usual warming we would see by 2100 of a catastrophic 7.8°C (14°F) — if the climate response is at the high end of the estimated range, which is more likely than it being at the low-end range.

In most aspects of our lives, however, humans — at an individual and societal level — are very risk-averse, particularly when it comes to life-changing or catastrophic or irreversible risks. That is why we buy fire insurance even though the chances of losing your home to fire are quite small (unless you live in a known wildfire zone). That is also why we buy catastrophic health insurance; not because we expect to get cancer, but because we know that if we do and do not have insurance, the result might be bankruptcy on top of the illness. Worst-case scenario planning has also driven a considerable amount of government spending for the military and epidemic-prevention.

What little economic analysis has been done in this area suggests that worst-case scenarios for climate change — a scenario with relatively low probability and high catastrophic damages — can potentially dominate calculations of things such as the “social cost of carbon” or the total cost to humanity of climate inaction.

The scenario I described in my 2016 book would probably be described by most as “high catastrophic damages,” but it is merely close to the business-as-usual set of impacts according to the most recent observations and scientific analysis. These include widespread drought, mass species loss on land and sea, increase in the most extreme type of weather events globally (including heat waves and superstorms), sea-level rise greater than 6 feet by century’s end with seas rising up to a foot a decade after that, the resulting increases in salt water infiltration and storm surges globally, and all these effects combining together to present myriad threats to human health, national security, and our ability to feed a population headed toward 10 billion people.

The generally cautious and conservative IPCC warned that these impacts would lead to a “breakdown of food systems,” more violent conflicts, and ultimately threaten to make some currently inhabited and arable land virtually unlivable for parts of the year.

In addition, we also face: the destruction of much of the permafrost and Amazon carbon sink, the potential for the continued clogging up and weakening of other key carbon sinks, such as the oceans and soils, and longer term, potentially the thawing of the methane hydrates, which are frozen methane crystals under the permafrost and in the ocean. However, even though we know they are at risk, many of these key carbon cycle amplifying feedbacks (such as the loss of the massive amounts of carbon from the permafrost) are not even found in the most widely used climate models.

In 2010, the Royal Society devoted a special issue of Philosophical Transactions A to look at this 4°C (7°F) scenario. It notes that “in such a 4°C world, the limits for human adaptation are likely to be exceeded in many parts of the world, while the limits for adaptation for natural systems would largely be exceeded throughout the world.” The UK’s Guardian notes “A 4°C rise in the planet’s temperature would see severe droughts across the world and millions of migrants seeking refuge as their food supplies collapse.”

Again, this 4°C world is not the plausible worst-case, it is close to the expected outcome of our current emissions pathway.

There has not been much modeling at all of what temperatures that high would mean for Homo sapiens. NOAA did explore the impact of that kind of heat stress on productivity in a 2013 study:

Global warming of more than 6°C (11°F) eliminates all labor capacity in the hottest months in many areas, including the lower Mississippi Valley, and exposes most of the U.S. east of the Rockies to heat stress beyond anything experienced in the world today. In this scenario, heat stress in NYC exceeds present day Bahrain, and Bahrain heat stress would induce hyperthermia in even sleeping humans.

As we go past 4°C warming, we put ourselves at greater and greater risk of making large parts of the planet’s currently arable and populated land virtually uninhabitable for much of the year and irreversibly so for hundreds of years.

“When it comes to evaluating the risk of carbon emissions, such worst-case scenarios need to be taken into account,” explained Purdue professor Matthew Huber. “It’s the difference between a game of roulette and playing Russian roulette with a pistol. Sometimes the stakes are too high, even if there is only a small chance of losing.”

The very worst-case scenario for climate change is unimaginably horrific. The plausible worst-case scenario is imaginably horrific — and it’s not much different from the world we end up with if the climate policies of Trump and the GOP leadership continue to prevail in this country past 2020.

So while the NY Magazine piece isn’t framed perfectly, and has a few errors of fact that others have identified, I would urge everyone to read it. The piece is one of the few recent discussions in a popular magazine to try to spell out just how bad things could get.

If we keep acting like the “This is fine” dog, we may end up like him, too.