In a ruling with substantial importance for water management in the American West, a U.S. appeals court upheld a lower court’s decision that an Indian tribe in California’s Coachella Valley has a right to groundwater beneath its reservation.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit determined on March 7 that when the federal government established a reservation in 1876 for the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians — on arid land without the endowment of significant rivers or streams — water was part of the deal. The existence of the reservation confers to the tribe the right to groundwater, the court concluded.

“The creation of the Agua Caliente Reservation therefore carried with it an implied right to use water from the Coachella Valley aquifer,” Judge Richard Tallman wrote in the 22-page opinion.

The Agua Caliente’s lawsuit reflects the growing willingness of Indian tribes to exercise their legal muscle, either by settlement or lawsuit, to protect their access to water supplies. Tribal actions in the 1980s to stake claim to surface water and groundwater through negotiated settlements have now expanded into legal arguments that assert authority over groundwater resources.

The lawsuit could also signal an expansion of federal jurisdiction over groundwater, which to this point, has been largely confined to state law. After an outcry two years ago from western governors and members of Congress, the U.S. Forest Service withdrew a groundwater management directive that some interpreted as encroaching on a state privilege.

The Agua Caliente filed the initial lawsuit in May 2013 against the Coachella Valley Water District and the Desert Water Agency, two water suppliers near Palm Springs that also deliver water to the tribe. The U.S. government later sided with the tribe.

In their decision the Ninth Circuit judges affirmed that the Winters doctrine of reserved water rights, traditionally applied to tribal claims to water from rivers and streams, also applies to groundwater. The Winters doctrine stems from a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case in 1908 that held that when the federal government withdraws land from public use, such as for establishing a reservation, it also sets aside water to meet the purposes of that land.

Federal courts have interpreted the doctrine broadly, using it to secure water for a national forest in New Mexico and prohibit groundwater pumping that was depleting the habitat of an endangered fish in Death Valley National Monument. The latter case was the first time a federal court asserted a reserved right to groundwater.

Local and National Implications

Until the U.S. District Court of the Central District of California ruled in favor of the Agua Caliente on March 20, 2015, only one other federal court had applied the reserved right to a tribe’s claim to groundwater. The Ninth Circuit ruling today upheld those precedents for a jurisdiction that covers nine western states.

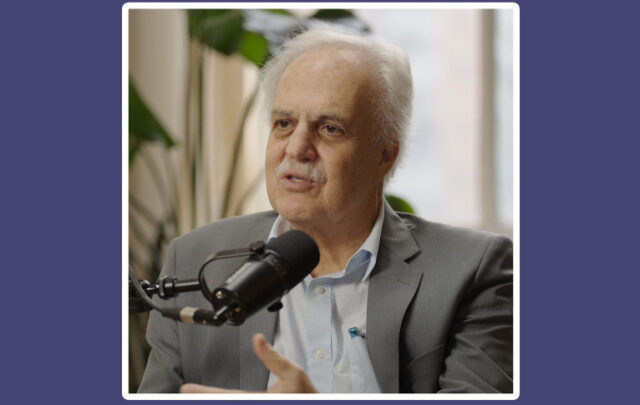

“At least within the Ninth Circuit, it should settle once and for all the question of whether the Winters doctrine extends to groundwater,” said Reed Benson, a University of New Mexico law professor.

Robert Glennon, a University of Arizona law professor who specializes on water policy, said that the ruling is “a huge first step for Indian water rights in the West.” He said it may influence water rights negotiations for the Navajo and Hopi, desert tribes with few rivers and with two of the largest outstanding claims to water in the western United States. Both tribes are located on land within the Ninth Circuit’s jurisdiction. Benson said that he expected the ruling to strengthen tribal negotiating positions in settlements.

Roderick Walston, a lawyer representing the Desert Water Agency, called the ruling “sweeping and broad” and said that it could apply not only to Indian reservations but to national parks, military bases, and other federal reserved lands.

The decision has local implications as well. More water is withdrawn from the Coachella Valley groundwater basin than is sustainable. The valley receives between three and five inches of rain per year. The two water supply agencies recharge the aquifer with water imported from the Colorado River, which is saltier than local groundwater. The Agua Caliente filed its complaint in part to prevent the continued depletion of the aquifer and to play a larger management role. That could mean that the tribe would seek to limit pumping. The water agencies are certainly concerned. In a brief filed with the appeals court last October, their lawyers argue that granting a reserved groundwater right to the Agua Caliente would “jeopardize the rights of other groundwater users.”

The Agua Caliente lawsuit is divided into three phases. Phase one, now before the court, seeks to establish whether the tribe has reserved rights to groundwater. The second phase will address whether that water must be free from pollutants. The final phase is perhaps the most complex: quantifying the tribe’s groundwater rights.

The Ninth Circuit opinion adds to state Supreme Court rulings in Arizona and Montana in the last two decades that have affirmed tribal groundwater rights. But as Steve Greetham, counsel for the Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma pointed out to Circle of Blue in an interview two years ago, there is no common standard for states to follow. The Arizona court, for instance, recognized tribal rights to groundwater but only if surface water is insufficient.

Glennon thinks the wording of the Ninth Circuit’s opinion is along similar lines, granting rights based on the availability of surface water. Judge Tallman makes frequent reference in the opinion to the reservation’s arid climate and lack of streams. “Survival is conditioned on access to water — and a reservation without an adequate source of surface water must be able to access groundwater,” Tallman wrote. This is a more constrained reading of the ruling than Walston’s broad interpretation. Regardless, the case is ripe for further review.

“At the end of the day, this is a federal issue,” Glennon told Circle of Blue. “At some point the Supreme Court will need to resolve it.”

Walston said that the water agencies are considering two responses: petitioning the entire Ninth Circuit to review the ruling or submitting the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. They have 45 days to file the first petition and 90 days for the latter.

“We’re consulting about the best steps,” Walston told Circle of Blue. “There are no decisions at this point.”

Teaser photo credit: courtesy of Flickr/Creative Commons