Banks. We can’t live with them, we can’t live without them. Yet. Much has been written about the role of banks in creating austerity, and coercing whole nations to dismantle and sell off public services and national assets, while being bailed out by the very people who depend on them. But banks do provide essential functions and no doubt employ many good and talented people who love their pets and are motivated to help their communities. So here’s an interesting one for you to ponder, and to hopefully debate below. How would the world be if cash machines were able to issue local currency?

We just passed the 50th anniversary of the invention of the ATM, the cash dispensing machines that are now such a part of our lives. We recently learned that James Goodfellow, the inventor of the technology, only earned £10 for the patent, and has never received any subsequent income from his invention.

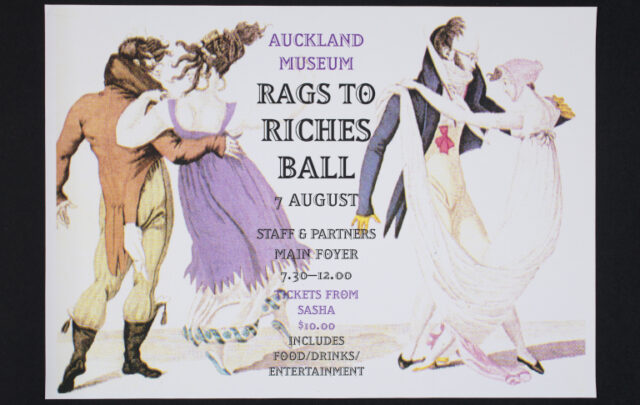

It was recently announced that the Brixton Pound launched the UK’s first local currency cash machine in Britain. And a thing of beauty it is too (see above). The cash machine was funded through the Mayor of London’s High Street Fund, and was designed by Kind Studio, a local design agency. It even made the local BBC News. B£’s Tom Shakhli said:

“Our cash machine is the latest in our challenge to the conventional view that we’re moving towards a cashless society, and gives locals and visitors to Brixton an opportunity to experiment with money that celebrates community and creates conversations rather than closes them off.”

The Brixton Pound’s cash machine is actually a repurposed snack vending machine. Something I have wondered about for ages though is what a leap forward it would be for local currencies if conventional ATMs gave you the option, when you put your card in, of Sterling or local currency. Something like this:

I’m rather torn on this. So first I’m going to give you the case for, and then the case against.

The Case For Cash Machines Issuing Local Currencies

It would be a huge coup for the first bank to do it, a good publicity windfall, an ingenious piece of enlightened corporate social responsibility, as well as being a huge service to the local community.

I asked Ciaran Mundy of the Bristol Pound, the UK’s leading local currency scheme, about the idea. Turns out they are working to try and get such a machine at Temple Meads station, but it has yet to happen. Some ATMs, it turns out, are run by banks, but an increasing amount these days are run by private companies. Their most recent re-issue of notes were designed to be ATM-compliant, so if any bank decided to design them into their ATMs it would be possible.

What would be in it for the local currency scheme? It would remove a barrier to engagement in terms of the perceived hassle of getting money changed over. It would ‘normalise’ it for those currently on the fringes of engagement, making it more part of everyday life. It would be the most wonderful publicity for the whole scheme.

And for the banks? It would be a huge PR boost. The first ATM to do this would become a pilgrimage site for people around the world. It would make that bank branch really stand out as different, as cool, as innovative. It would enable the bank itself to potentially deepen its links to its local economy and to local businesses, being a much more visible part of that. It would be a good way to counter perceptions around greedy banks, by issuing a currency people would know would never end up in the Cayman Islands. It would be a move that would support banks’ existing commitment to sustainability and CSR.

The Case Against Cash Machines Issuing Local Currencies

Well, much of the above really. Do we really want to give banks the good PR that would come from issuing local currencies? Do we want to allow them to create the illusion that they care about local economies when it is clear from the way they operate that they don’t? Do we want to enable them to create the illusion of being innovative that they haven’t earned?

Also, it is the banks largely who are leading a drive to get rid of cash altogether. In 2014, in the UK for the first time, cashless payments overtook cash payments. Research shows that 71% of people in the UK carry less than £20 in cash with them at any one time, and a quarter of those asked said that they would leave a shop that didn’t take cards to find one that did. Buses in London have been cashless since 2014. In Belgium, 93% of transactions are now made without the use of cash. There are those, such as German economist Peter Bofinger, who argue for a ban on cash, calling it an "anachronism", telling Der Spiegel "the markets for undeclared work and drugs could be dried out, and central banks would find it easier to enforce their monetary policies."

There are very real concerns about a move towards a cashless society. Rainey Reitman, activism director at the Electronic Frontiers Foundation, says "when all our payment transactions are tracked, it creates a trove of data we have no control over. It’s easy to imagine a daring divorce lawyer or a government agent trying to gain access to our financial history to try to build a story about who we are." There are also concerns about privacy, about surveillance, about the data regarding our transactions being bought and sold by private companies. In this context, simply using printed local currencies can be seen as an act of resistance, solidarity or defiance.

Also we mustn’t forget that a significant number of people don’t have bank accounts, being what is referred to as "unbanked". In the US, that’s 8% of the population. Yet there is also an argument, made by Charlie Sorrel at fastcoexist.com, that a cashless society offers new opportunities to ‘localise money’ in the way local currencies attempt to do at present:

"The kinds of rules that are applied to hyper-local currencies could also be useful on a wider scale. When money is all electronic, instead of hard-to-track paper, you can experiment with innovations in monetary policy far more easily than when a lot of the money in the system exists as cash in people’s pockets. For instance, all money could be set to automatically devalue itself slowly, encouraging its owners to spend it. This makes huge cash hoards less useful, and—like the Greek TEM’s ceiling—keep money flowing. Electronic cash also allows the spender to attach certain caveats to their purchases, like how we can already use the Creative Commons to say how our copyrighted works can be used. For instance, you could earmark your electronic cash as ethical, so it could only be spent at other ethical places down the line. This may devalue the "cash," as it becomes less useful, but you would assume the extra cost up front, similar to how we already pay a premium for ethically produced foods. Or parents could restrict their kid’s allowance to only be spent on wholesome pursuits, like books, or prohibit it from being used in fast-food restaurants".

We should also remember that several local currencies, Bristol, Brixton, Totnes and Exeter, are now running an electronic version of their currencies via a Text2Pay, mobile phone-based currency. Indeed the Bristol Pound see the electronic version as being what they really want to build, the printed notes being seen more as advertising for the phone-based version. Perhaps, if ATMs did issue local currencies, that they might also give people the opportunity, in the way they currently do for charities or deserving causes, to support, Local Entrepreneur Forum-style, an emerging local enterprise? They could be a way that people could vote in a local referendum, or in decisions around Participatory Budgeting.

Over to you…

So as this point we hand it over to you. Should banks be invited to issue local currency notes? Would it be backing up the very system we would like to replace with something else? Would it be a fig leaf for a system that has run very low on legitimacy? Or could it offer us the possibility of ‘normalising’ local currencies, of reaching people such schemes currently bypass? Would we be best, like Brixton, to create our own cash machines, however rudimentary? We’d love to hear your thoughts.

Credit: Arlo Murray Hopkins