Click on the headline (link) for the full text.

Many more articles are available through the Energy Bulletin homepage.

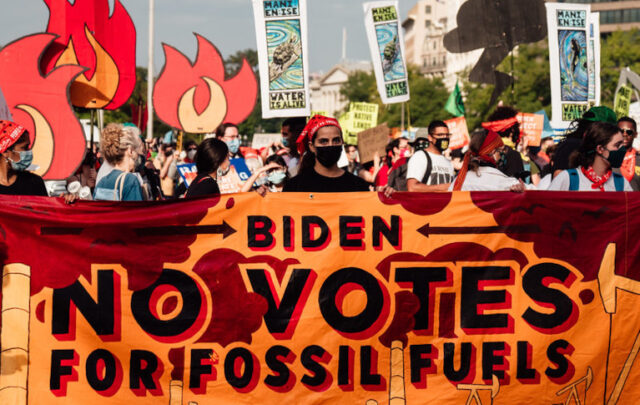

We need big, brash, nonviolent climate protests. Are you in?

Bill McKibben, Philip Radford, Rebecca Tarbotton, Grist

Dear friends,

Last week, a jury in Utah found Tim DeChristopher guilty for standing up to the oil and gas companies in an effort to protect our health and our climate.

If the federal government thinks that it’s intimidating people into silence with this kind of prosecution, think again. This is precisely the sort of event that reminds us why we need creative, nonviolent protests and mass mobilizations.

Over the last six months, we’ve witnessed big changes in the world that call out for creative, nonviolent protest, including:

- * The wild and extreme weather and flooding that marked the end of the warmest year on record

- The complete collapse of efforts on Capitol Hill to do anything about climate change

- The Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, which grants corporations unfettered influence over our elections

We’ve also seen a historic outpouring of people power to combat environmental crises, reclaim our democracy, and disrupt corporate influence. From the exhilarating outbreak of the freedom movement across North Africa and the Mideast to the amazing stand for democracy and workers’ rights in Wisconsin, we are seeing the strength and effectiveness that average people can have when we stand together.

There have also been inspiring examples of civil disobedience across the United States to protect the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the climate that we depend on.

… We worry that we may have waited too long to get this battle going in earnest; the science is dark, and the politics are tough. But we know, from watching our inspiring colleagues around the world who are facing great dangers head-on, that the best time to act is now. Over the coming weeks, each of our organizations, working together and individually, will be pursuing a variety of strategies to try and spark more mass, direct action.

Tim DeChristopher took a brave and lonely stand; it’s time to make sure that in the future bravery comes in bigger quantities.

Bill McKibben, 350.org

Phil Radford, Greenpeace USA

Becky Tarbotton, Rainforest Action Network

(7 March 2011)

Suggested by Post Carbon Institue who writes: “A call to action by PCI Fellow Bill McKibben and others…” -BA

Facebook and Twitter are just places revolutionaries go

Evgeny Morozov, Guardian/UK

Cyber-utopians who believe the Arab spring has been driven by social networks ignore the real-world activism underpinning them

—

Tweets were sent. Dictators were toppled. Internet = democracy. QED.

Sadly, this is the level of nuance in most popular accounts of the internet’s contribution to the recent unrest in the Middle East.

It’s been extremely entertaining to watch cyber-utopians – adherents of the view that digital tools of social networking such as Facebook and Twitter can summon up social revolutions out of the ether – trip over one another in an effort to put another nail in the coffin of cyber-realism, the position I’ve recently advanced in my book The Net Delusion. In my book, I argue that these digital tools are simply, well, tools, and social change continues to involve many painstaking, longer-term efforts to engage with political institutions and reform movements.

…while the recent round of uprisings may seem spontaneous to western observers – and therefore as magically disruptive as a rush-hour flash mob in San Francisco – the actual history of popular regime change tends to diminish the central role commonly ascribed to technology. By emphasising the liberating role of the tools and downplaying the role of human agency, such accounts make Americans feel proud of their own contribution to events in the Middle East. After all, the argument goes, such a spontaneous uprising wouldn’t have succeeded before Facebook was around – so Silicon Valley deserves a lion’s share of the credit. If, of course, the uprising was not spontaneous and its leaders chose Facebook simply because that’s where everybody is, it’s a far less glamorous story.

Second, social media – by the very virtue of being “social” – lends itself to glib, pundit-style overestimations of its own importance.

Evgeny Morozov is the author of the Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. He is a contributing editor to Foreign Policy and runs the magazine’s Net Effect blog. He is a visiting scholar at Stanford University and a Schwartz fellow at the New America Foundation.

(7 March 2011)

Controversialization: A Key to the Right’s Continuing Domination of Public Debates

Thomas S. Harrington, CommonDreams.org

Yesterday, our local NPR station hosted a debate about what themes should and should not be included in school-sponsored drama productions. The discussion followed a pattern that has become quite familiar on our airwaves within the last three decades. In this oft-repeated dance, an earnest moderator conducts a series of interviews guided by what he or she portrays as a desire to find the appropriate “balance” between our constitutionally guaranteed rights to free expression and the possibility imposing “offensive” messages upon an unwitting public.

At first glance, this line of inquiry would appear to have few, if any, real drawbacks. After all, those of us of a certain age know that life is often about balancing what we have a formal right to do or say against that same action’s potential for generating negative or disagreeable side effects.

But when we look at this practice of automatically seeking balance in a different light–one that takes into account the widespread use of what the investigative journalist Robert Parry calls the practice of “controversializing”–we can see how it has greatly lowered quality of our civic discourse.

At the core of the practice of controversializing is an age old political problem: how to get your way–or at least seriously blunt the prerogatives of your opponent–when you enjoy neither strong popular support nor a clear-cut legal basis for instituting your ideological project.

This is exactly where the American Right found itself in 1971. At that moment, long-standing American business and military elites were reeling. Disaffection with the Vietnam War, and the entire establishment that was seen as having created it and having sustained it, was enormous, especially among the huge and ever more politically crucial Baby-boomer demographic. Moreover, for the first time in the Post World War II era, large parts of the mainstream media were actively and openly questioning the wisdom of top-level players in Washington and in the highest levels of corporate America.

It was precisely at this juncture that Lewis Powell, a corporate lawyer still two months removed from his elevation to the Supreme Court, laid a out a blueprint for an Establishment counterattack on what he saw as the fast-rising hegemony of the Left in this country. He did so in a memo to his friend Eugene Sydnor, the head of the powerful US Chamber of Commerce.

Thomas Harrington is Associate Professor of Iberian Studies at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut.

(6 March 2011)

The problem with the strategy of controversialization is a “spoiler” strategy — it prevents monitoring for problems and developing a constructive response. Hat tip to Gerry G. -BA

2011 is 1848 Redux. But Worse

Robert Freeman, CommonDreams.org

n 1848, a series of revolutions convulsed Europe. From Berlin to Budapest, Venice to Vienna, Paris to Prague, people rose up and overthrew the authoritarian monarchies that Metternich had installed in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. It was these revolutions that prompted Karl Marx’s opening words of The Communist Manifesto: “A specter is haunting Europe. It is the specter of communism.”

Of course, Marx was wrong. The specter of rebellion was more one of nationalism, and to a lesser extent, liberalism. More importantly, all the revolutions ultimately failed. They were all defeated by monarchical forces which mounted counter-revolutions and routed the insurrectionists. Though many governments made token concessions to the rebels, all maintained, and in some cases strengthened, their authoritarian rule until finally, decades later, they could no longer suppress the impetus for change.

This is the important lesson that history has for the rebels of 2011. Euphoria is not victory. The removal of symbols is not the change of regimes. Whether in Athens or Cairo, Bahrain or even Wisconsin, the revolutions will not be won in the streets. They will not be won early. They will be resisted fiercely, cleverly, tenaciously, and with all the resources that the assaulted powers can muster, including the most important resource of all: time.

If the revolutions of 2011 are to succeed — and it’s a big if in every case — several things need to occur. The grievances must be extended beyond the core of protesters and taken up by their larger populations. The protesters must seize control of not just city squares and capitol buildings, but the institutions of power themselves. And the protests must be sustained, for years if necessary, until fundamental change is secured. These will be extremely high hurdles to clear but unless they are, the revolutions will ultimately fail.

… What can we learn from this not-so-ancient history that might improve the chances of success for the revolutions of 2011?

The first thing is that nobody should have any illusions that the existing orders are going to go quietly into the night. They are too deeply entrenched, too convinced of their entitlement to power, have too many resources at their disposal, and have too much to lose by easy capitulation. They will use every trick in the book to undermine the cohesion, commitment, and resilience of the protesters.

In Jordan and Bahrain, for example, the governments have nakedly moved to buy off the protesters. In the case of Saudi Arabia, the extremely authoritarian, honestly, medieval, government announced mass disbursements to all citizens amounting to thousands of dollars per person.

Each of these countries are critical to U.S. strategy in the Middle East. Jordan is critical to U.S. support for Israel. Jordan supported Jews against Palestinians in the war of 1948 that made Israel a state. Bahrain hosts the U.S. Fifth Fleet which keeps control of the Persian Gulf. And Saudi Arabia sits atop 25% of the world’s known oil reserves. We may assume each has a blank check on U.S. resources to help defeat their peoples’ revolutions.

In each of these states, the revolutionaries, though righteous and adamant, have no experience in the exercise of state power, or of any institutional power for that matter. This proved fateful for all of the revolutions of 1848.

(6 March 2011)