This is the third in the Metastatic Modernity video series of about 17 installments (see launch announcement), putting the meta-crisis in perspective as a cancerous episode afflicting humanity and the greater community of life on Earth. This episode stresses that humans are nothing without the menagerie of single-celled pioneers whose many clever solutions to life we still utterly depend on today.

As is the custom for the series, I provide a stand-alone companion piece in written form (not a transcript) so that the key ideas may be absorbed by a different channel. The write-up that follows is arranged according to “chapters” in the video, navigable via links in the YouTube description field.

Introduction

After the standard introduction of series title and my name, I indicate that the topic is on early life—as the next step in our journey to put modernity into context.

Timeline of Life

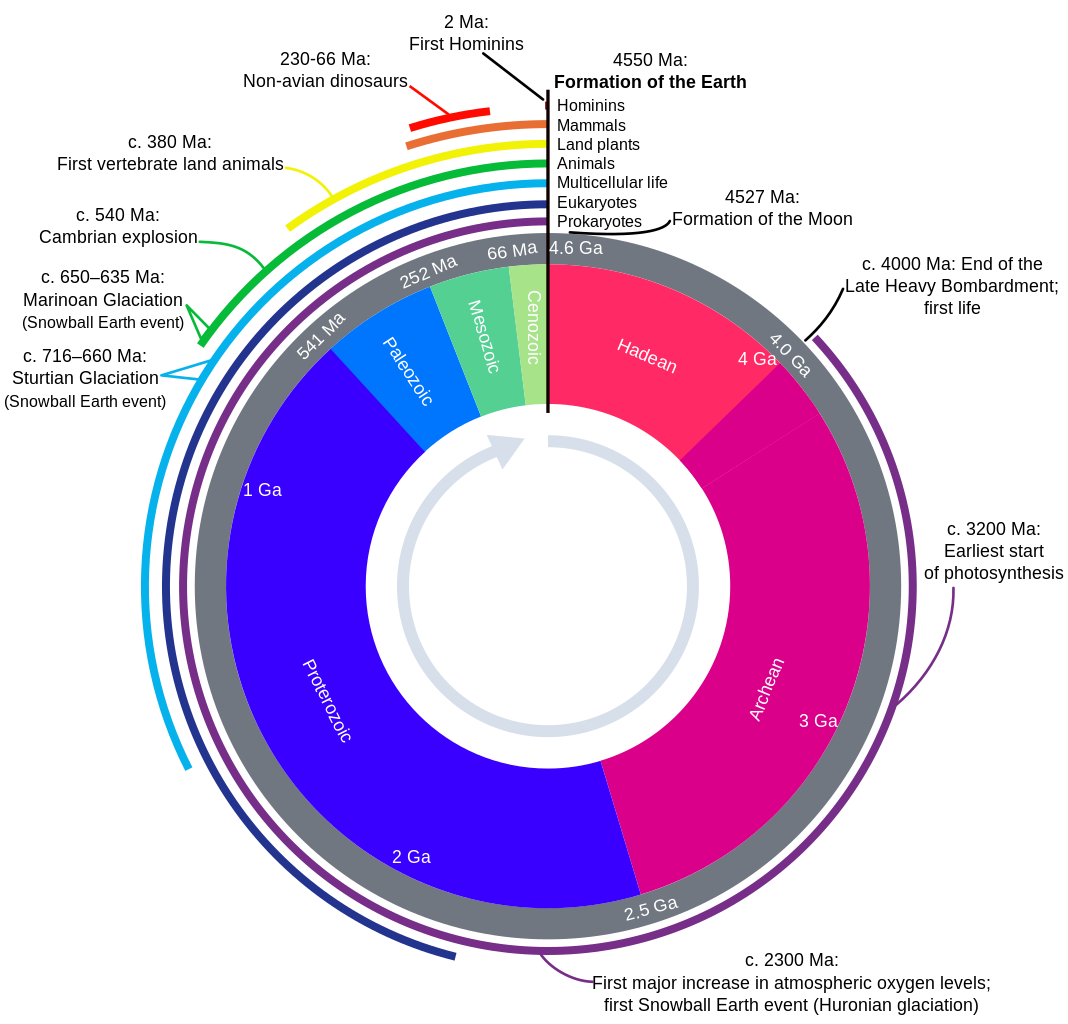

This segment relies heavily on a graphical representation of the timeline for life on Earth.

From Wikimedia Commons

Earth formed about 4.55 billion years ago (therefore a third of the age of the universe), and life started not too long after: within about a half-billion years—or about 4 billion years ago—once the period of heavy bombardment subsided.

Referring to events by the corresponding time on a 12-hour clock face where Earth formation is at noon (“now” is midnight), life started at around 1:30 in the afternoon. Photosynthesis began around 3:30, and the atmosphere was oxygenated by 6:00.

Single-celled eukaryotes—our brand of life—came onto the scene around 6:30, branching into multi-cellular life a little after 8:00. Some time passed until the first animals show up a little after 10:00.

The Cambrian Explosion—when biodiversity suddenly went bananas, nuts, ape (all of which came later, actually)—was around 10:30 (540 million years ago). It was approaching 11:00 before plants began their land invasion, soon followed by ravenous animals.

Around 11:20 to 11:30 the first mammals and dinosaurs came about, the latter group disappearing at 11:49. Within 2–3 minutes of the dinosaurs’ disappearance, mammals had taken to the air and seas in the form of bats and cetaceans. Humans appeared about 25 seconds before midnight, 2.5–3 million years ago. Agriculture began 0.1 seconds before midnight: the blink of an eye.

Boring? Hell No!

It’s tempting to say that for most of the first 3.5 billion years of life, it was pretty boring: things didn’t start to get exciting until the Cambrian Explosion at 10:30. I want to try to convince you otherwise. Life was far from idle during those 3.5 billion years. That’s the period during which life solved the hardest problems of how to live as an organism on our planet, constantly innovating.

It’s an incredible story—a monumental accomplishment that is absolutely crucial to human survival.

The Amazing Amoeba

To illustrate this, I will use the amoeba as an example. Some might call the amoeba “lowly,” but I take offense to this, for reasons that will become clearer.

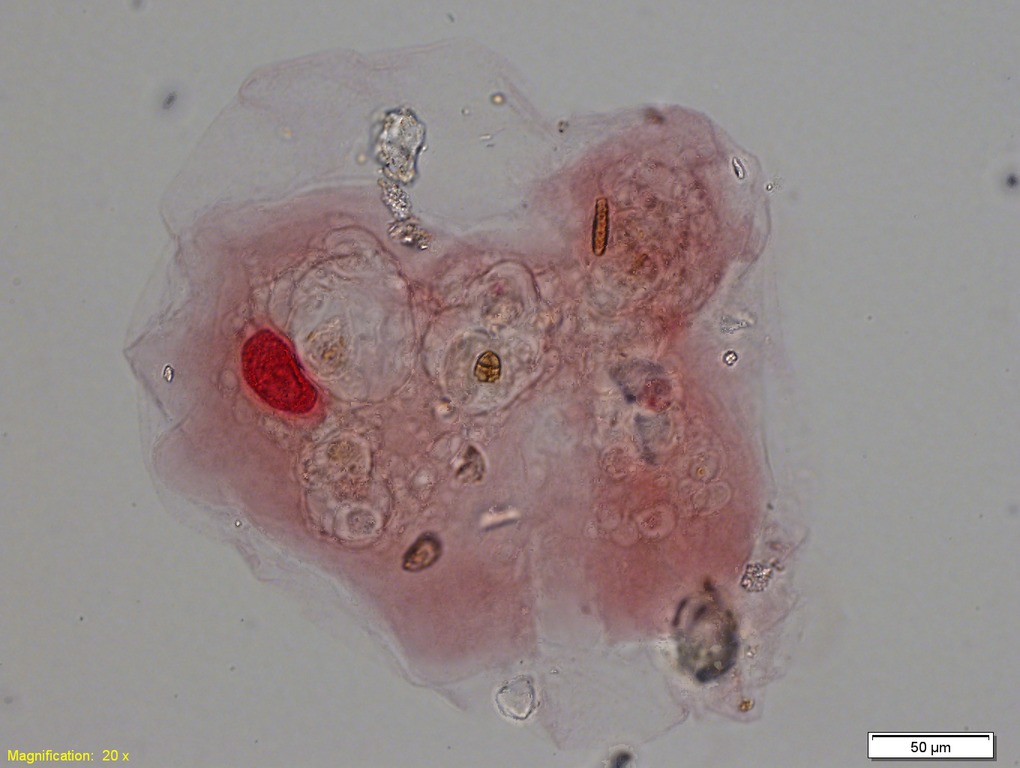

Photo by Thierry Arnet via Wikimedia Commons

An amoeba has something like 13,000 genes, which isn’t all that different from the roughly 20,000 genes in a human. Moreover, and this fact I think carries almost the whole point of the episode: humans utilize about a third of an amoeba’s genes. Yeah. Incredible. We’re much more closely related than one might naively imagine. We don’t look 30% similar at first glance. Yet, we share a lot of commonality with amoebas. We are kin.

Single-Cell Solutions

How does this kinship show up, when it’s not readily apparent? Well, all life has to face a number of shared challenges, and we therefore share solutions (meaning we inherited them from early life). I’ll enumerate a partial list:

- Replication: A defining characteristic of life is the ability to replicate, which all life on Earth carries out through the medium of RNA and/or DNA. This is a truly astonishing process in its speed, complexity, and efficiency—worked out very long ago. It was such a profoundly effective idea that life as we know it has not dared try anything different. This step was a heavy lift on the parts of the pioneers, to which we owe virtually everything.

- Protein Coding: The instructions contained in genetic codes largely consist of blueprints for building proteins—all utilizing the same basis of 20 amino acids. This may sound like no big deal, but it’s the whole ballgame, because…

- Protein Catalysis: Proteins are the workhorses on the “factory floor” of the cell, cleverly using shape and affinities to selectively grab building blocks from the surrounding soup and put them together in the correct orientations with other building blocks to create new functionalities. Left to their own, these blocks would be incredibly slow to find each other and happen to self-assemble correctly. Thus, proteins catalyze (speed up; promote) essential chemical reactions critical for life.

- Cell Membranes: A crucial function of a cell is to hold itself together, keep out unwanted agents, allow necessary nutrients in, and move waste out. The cell membrane accomplishes these mighty tasks, shared by all life today.

- Mobility: Getting around (or moving resources around) is important. The simple act of changing shape (e.g., contracting) is one common trick that our muscles still use to move us around: an ancient solution.

- Metabolism: All life needs energy to operate. We need to eat. The basic process of metabolism was worked out long ago. So successful was the solution, in fact, that later life co-opted bacteria into their cells as mitochondria. This cooperative heritage remains a key part of our every living moment today.

- Sensing: Life needs to be able to sense its environment through various channels: light, heat, chemical gradients, tactile information, vibration, etc. Those basic capabilities developed in the “boring” years and are vitally important to us today, often elaborated into complex structures.

- Environmental Tolerance: Conditions change, so organisms need to be able to adapt to light and dark, hot and cold, wet and dry, acidic and alkaline, etc. It’s a very impressive skillset to be able to navigate and procreate in the face of a dynamic world.

All these vital problems (and plenty more) were solved by early geniuses during the 3.5 billion year “boring” lead-up to “fancy” life.

We Have Nothing on Them!

These early lifeforms are such geniuses, in fact, that we are still scrambling to try to figure out what it is they’ve done. By no means do we have all the answers yet. We’re still playing catch-up, like overwhelmed students still having trouble following what the teacher just did in front of our eyes on the chalk board. They are the masters, not us. Truly. Having billions of years of robust accomplishment under one’s belt translates to quite an edge.

The things that humans build—cities, bridges, spacecraft, smart phones, you name it—absolutely pale in comparison to the complexity, sophistication, autonomy, and amazingness of life. We have never built anything even remotely as incredible as the simplest organism or virus. Our machines are pathetic dead-end scrap piles by comparison.

I’ve invented, designed, and built a number of “sophisticated” assemblies in my life to perform novel tasks. Perhaps the most complex was an apparatus to bounce laser pulses off the reflectors left by astronauts on the moon, measuring round-trip time and thus Earth–Moon distance to one-millimeter accuracy as a test of general relativity. Dozens of subsystems had to interact (correctly) in order to coordinate this challenging measurement. I would say it was no small feat. Yet, it can do almost none of the basic things a living organism can. It’s painfully narrow and fragile. It’s not even in the same galaxy as an amoeba in terms of sophistication, adaptability, and longevity.

Nothing that we build comes even close to the amazingness of life.

Amoebas as Geniuses

Resonant with this point, I recommend Ze Frank’s video on how smart slime molds can be, even by our silly metrics. These amoebas can remember where they’ve been, solve mazes by the most efficient paths, learn how to do new things and even pass on that knowledge to others they come into contact with. They also designed a light-rail transit system for the Tokyo region whose efficiency and effectiveness were comparable to what human engineers actually built. Again, these may be trivial, silly measures of smartness next to the much more impressive feat of figuring out how to replicate, move, eat, and survive. We have a funny way of measuring intelligence (stacked so that we win?). In any case, amoebas (and other microbes) are pretty amazing creatures to whom we don’t give enough credit.

Nothing without the Boring Years

The main point is that we are nothing without that 3.5 billion years of life solving the hardest problems. Sure, we possess the same biological skillset, but only by inheriting or copying the key features of life: not by solving from scratch—and definitely not derived in our brains. We rely on our pioneering ancestors every second of every day.

Without that foundation, we could not exist as humans. It doesn’t even make sense to talk about the idea of humans without the foundation laid by our microbial forebears. Plenty of embellishments were added to the foundation, and these deserve admiration as well (virtually none of them human-created). But even these are utterly reliant on the foundations established by early life.

A Big Deal!

This foundation is such a big deal, and central to who we are, yet very under-appreciated. Here’s a suggested experiment to demonstrate the degree to which this key fact of life is not prevalent in our stories: try an internet search of the following sort:

problems solved by early life that we completely rely upon

Plenty of variants are possible as well, but it should be clear what I mean by this query. Try it (or your own variants) and see just how off-target the results are. Do any of the results discuss the points we’re covering here? How anthropocentric are the results? In my case, “early life” was interpreted to mean human children. Later attempts seemed to drop this interpretation, but then the word “problems” was taken to mean inadequacies in human frameworks, not about solving the basic problems of how to be a replicating, living being. The point of this for me is to expose just how off-the-radar this topic is in our cultural milieu.

Utter Dependence

What I am trying to do is plug a big gap in our perspective. We have forgotten who we are and where we come from. We essentially pay no heed to our ancient ancestors—the pioneers of life. Yet without them having done what they did, we would be nothing. We couldn’t exist. We absolutely, crucially, vitally, every second of every day, depend on what they figured out—most of which is still mysterious to our brain-works.

I want to encourage you to try a little bit of awe for early, microbial life. Try some respect; try seeing yourselves from a position of humility, and extend admiration for the genius that we take for granted, but that is absolutely crucial to being who we are.