I expected this to happen, perhaps not so soon and not in this form, but it had to come. With the era of cheap fossil fuels coming to a close, what’s left as low-cost fuel is wood and that had to be the target of the next wave of exploitation. Naively, I was thinking that the rush to wood would have taken the form of desperate people moving to the woods with hand-held axes, but no, in Italy it is coming in a much more destructive way. It is a government decree approved on Dec 1st, 2017 which allows local administrations to cut woods, even against the will of the owners of the land. It is the start of a new wave of deforestation in Italy, probably an example that the rest of the world may follow in the near future.

It is a long story that goes back to the roots of Italian history. Already in Roman times, deforestation was a major problem, believed to have generated the marshes still present in Italy in modern times. During the Middle Ages, woods returned and were cut again in several cycles, the last one coming with the political unification of Italy, in 1861. At that time, the Piedmontese government treated the newly acquired lands as spoils of war, razing down ancient forests without any regrets. The story is reported in a novelized formby the British writer Ouida, in “A village commune.” (1881).

Gradually, with fossil fuels becoming more and more important – first coal, then oil and gas – trees ceased to be the crucial economic resource they had been before. In the 1920s the Italian government engaged in a serious reforesting policy whose effects are still visible nowadays. After the end of the war, in 1945, the Italian economic system prospered mainly on industry. For the local administrations, the main source of revenue was concrete and that led to the paving of large areas with buildings of all kinds, but the woods in their mountains were left more or less in peace. With agricultural land left abandoned, in many places woods advanced and covered new areas.

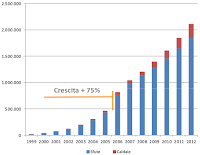

Then, there came the 21st century and with it the increasing costs of fossil fuels. Prices have been going up and down, generating occasional screams of “centuries of abundance.” But, by now, nobody sane in their mind can miss the fact that the old times of cheap fuels will not come back. One consequence has been the diffusion of pellet-fueled stoves in Italy, often done in the name of “saving the environment.” (figure on the right, source) Theoretically, wood pellets are a renewable fuel – but only theoretically. If they are consumed faster than trees can regrow, they are not. And the appetite of Italy for pellets is insatiable: Italians consume 40% of all the pellet burned in Europe while Italy produces only about 10% of the wood it burns.

With the housing market stagnating, someone was bound to realize that the only remaining source of profit from the land would come from turning forests into pellets. The consequence is the just approved evil piece of legislation. All in the name of the universally agreed concept that a tree is worth something only after it is felled, the new law gives to local administrations the power to cut everything, when they want, as they want. Let me leave the description of this disaster to my friend and colleague Jacopo Simonetta, writing in a recent post in “apocalottimismo“.

[The law] says that if the landlords refuse to cut the woods they own, the local administrators can occupy – even without the landlord’s agreement – the land and leave the “productive recovery” (that is the cutting of the trees) to companies or cooperatives of their choice (which means, “the friends of their friends”). And not just that. The companies which obtain the grant to cut the trees will provide economic compensation to the city administration in a form that the administration will define. For example, new streets, new parking lots, new street lighting, or anything the mayor will deem necessary for his or her electoral campaign. Or in the form of money, this time to the regional government, in order to “cash in” something – as people say.

It is easy to see here the hidden hand of the pellet industry, but there is – or at least there will be – much more. Anyone who has a minimum knowledge of how the administrations of small towns in Italy work can understand how this law is a formidable incentive for every administration to install a gang of local notables who will organize squads of henchmen financed with the cutting of other people’s woods. And those who, like me, have 40 years of experience in these matters know that the line that separate a squad from a Fascist squad (a “squadraccia“) is thin and it tends to become thinner and thinner as the power of the state fades away.

From my personal experience, I can completely confirm Simonetta’s analysis. Even in the theoretically civilized Tuscany, the local administrations have little or no resources to enforce the law outside urbanized areas. What had saved the woods, so far, is that at least the national laws were rather strict in protecting trees and that provided at least a veneer of protection. Now, the central government has abandoned even the pretense of governing the territory, leaving it all in the hands of the local bosses. It is normal, the collapse of civilizations comes first and foremost with the collapse of the central authority.

You may wonder whether anyone in Italy is speaking against such a horrible law; shouldn’t the government protect people’s property, including woods? In practice, just a few of the usual suspects have been protesting: environmental associations, a few experts, university professors, and the like – all people without any real power in the Italian society. From everybody else, especially at the political level, the silence has been deafening.

It is understandable: fighting this law implies going against an unholy alliance of 1) local politicians looking for funds for their re-election, 2) people living in the countryside, desperate for a revenue of some kind, of any kind, and 3) city dwellers who want low-cost pellets to warm their homes. And if you are thinking of defending a forest you believe should not be destroyed, you don’t need to live in places where mafia rules to understand that “they” know where your children go to school.

In the end, it is all the result of the harsh law of EROI the energy return on energy invested. Humans exploit first the resources which give them the best yield (high EROI) and, in the recent history, these resources have been fossil fuels. Then, they move to progressively lower EROI resources. Now, it is the turn of woods in Italy, but it is not limited to Italy. Most civilizations of the past fell together with a wave of deforestation that destroyed their last resources. Ours is not different, why should it be?

But a battle is surely going to be lost only if one refuses to fight it. So, if you want to give your contribution to this probably unvinnable battle to help the Italian woods, you can sign this petition. And, who knows? It might do something.

As a final consideration, you surely noted that I mentioned the Fascist government as having protected the trees in Italy. Surely, it did that better than the democratic governments which preceded and followed it. You may also know about the case of Japan: during the Edo period, the Japanese government enacted draconian laws to protect the Japanese forests: the unauthorized cutting of a single tree could be punished with death.

Does that mean that we need an authoritarian government to keep alive the world’s forests (and with them, humankind)? Perhaps, but the problem is more complex than that. An authoritarian government is expensive – it needs a police, an army, a bureaucracy, a propaganda system, and more – all things which need resources to be maintained. In times of collapse, an authoritarian government cannot survive better than a democratic one. Right now, we are clearly moving towards more and more authoritarian forms of government, but that doesn’t seem to be leading to a better management of the ecosystem. Rather, these governments seem to be more adept at sponsoring the plunder of whatever is left.

What is needed for keeping the ecosystem alive is a stable economic system, which is exactly what we don’t have and we won’t have in the foreseeable future. So, it looks like we have to go through collapse. Then we’ll re-emerge, perhaps, wiser than before. In the meantime, we have to put up with the limits of human nature.