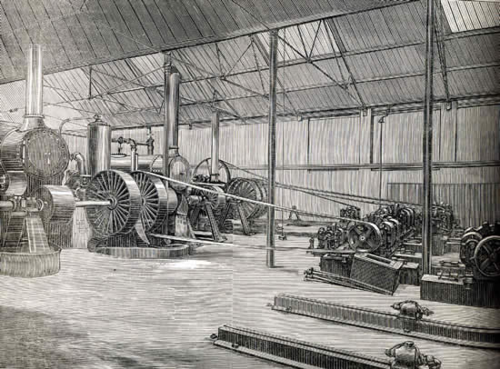

Picture: Brighton Electric Light Station, 1887. Stationary steam engines drive DC generators by means of leather belts. Source.

In today’s solar photovoltaic systems, direct current power coming from solar panels is converted to alternating current power, making it compatible with a building’s electrical distribution.

Because many modern devices operate internally on direct current (DC), alternating current (AC) electricity is then converted back to DC electricity by the adapter of each device.

This double energy conversion, which generates up to 30% of energy losses, can be eliminated if the building’s electrical distribution is converted to DC. Directly coupling DC power sources with DC loads can result in a significantly cheaper and more sustainable solar system. However, some important conditions need to be met in order to achieve this goal.

Electricity can be produced and distributed using alternating current or direct current. In the case of AC electricity, the current changes direction periodically, while the voltage reverses along with the current. In the case of DC electricity, the current flows in one direction and voltage remains constant. When electrical power transmission was introduced in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, AC and DC were competing to become the standard power distribution system — a period in history known as the "war of currents".

AC won, mainly because of its higher efficiency when transported over long distances. Electric power (expressed in watt) equals current (expressed in ampère) multiplied by voltage (expressed in volt). Consequently, a given amount of power can be produced by a low voltage with a higher current or by a high voltage with a lower current. However, power loss due to resistance is proportional to the square of the current. Therefore, high voltages are the key to energy efficient power transmission over longer distances. [1]

The invention of the AC transformer in the late 1800s made it possible to easily step up the voltage in order to carry power over long distances, and then step it back down again for local use. DC electricity, on the other hand, couldn’t be converted efficiently to high voltages until the 1960s. Consequently, it was impossible to transmit power effectively over long distances (> 1-2 km).

Illustration: Brush Electric Company’s central power plant dynamos powered arc lamps for public lighting in New York. Beginning operation in December 1880 at 133 West Twenty-Fifth Street, it powered a 2-mile (3.2 km) long circuit. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

A DC power network implied the installation of relatively small power plants in every neighbourhood. This was not ideal because the efficiency of the steam engines that powered the dynamos depended on their size — the larger a steam engine, the more efficient it becomes. Furthermore, steam engines were noisy and produced air pollution, while the low transport efficiency of DC power excluded the use of more distant, clean hydro power sources.

More than a hundred years later, AC still constitutes the basis of our power infrastructure. Although high-voltage DC has been gaining ground for long-distance transportation, all electrical distribution in buildings is based on alternating current, either at 110V or 220V. Low voltage DC systems have survived in cars, trucks, motorhomes, caravans and boats, as well as in telecommunication offices, remote scientific stations, and emergency shelters. In most of these examples, devices are powered by batteries that operate on 12V, 24V or 48V DC.

Renewed Interest in DC Power

Recently, two converging factors have renewed interest in DC power distribution. First, we now have better alternatives for decentralized power generation, the most significant of these being solar PV panels. They don’t produce pollution and their efficiency is independent of their size. Because solar panels can be located right where energy demand is, long distance power transmission isn’t a requirement. Furthermore, solar panels "naturally" produce DC power, and so do chemical batteries, which are the most practical storage technology for PV systems.

Secondly, a growing share of our electrical appliances operate internally on DC power. This is true for computers and all other electronic gadgets, as well as for solid state lighting (LEDs), flat screen televisions, stereo equipment, microwave ovens, and an increasing amount of devices operated on DC motors with variable speed operation (fans, pumps, compressors, and traction systems). Within the next 20 years, we could see as much as 50% of the total loads in households being made up of DC consumption. [2]

DC Power plant of the Hippodrome in Paris. A steam engine runs multiple dynamos that power arc lamps. Source unknown.

In a building that generates solar PV power but distributes it indoors over an AC electrical system, a double energy conversion is required. First, the DC power from the solar panel is converted to AC power using an inverter. Then, AC power is converted back to DC power by the adapters of DC-internal appliances like computers, LEDs and microwaves. These energy conversions imply power losses, which could be avoided if a solar powered building would be equipped with DC distribution. In other words, a DC electrical system could make a solar PV system more energy efficient.

More Solar Power for Less Money

Because the operational energy use and costs of a solar PV system are nil, a higher energy efficiency translates into lower capital costs, as fewer solar panels are needed to generate a given amount of electricity. Furthermore, there is no need to install an inverter, which is a costly device that has to be replaced at least once during the life of a solar PV system. Lower capital costs also imply lower embodied energy: if fewer solar panels and no inverter are required, it takes less energy to produce the solar PV installation, which is crucial to improve the sustainability of the technology.

A similar advantage would apply to electrical devices. In a building with DC power distribution, DC-internal electric devices can do away with all the components that are necessary for AC to DC conversion. This would make them simpler, cheaper, more reliable, and less energy-intensive to produce. The AC/DC adapters (which can be housed in an external power supply or in the device itself) are often the life-limiting component of DC-internal devices, and they are quite substantial in size. [2]

Illustration: Power driver for a 35W LED lamp. [3] All parts that are necessary for AC to DC conversion are marked.

For example, for an LED light, approximately 40% of the printed circuit board is occupied by components necessary for AC to DC conversion. [3] AC/DC adapters have more disadvantages. As a result of a dubious commercial strategy, they are usually specific to a device, resulting in a waste of resources, money, and space. Furthermore, an adapter continues to use energy when the device is not operating, and even when the device is not connected to it.

Last but not least, low-voltage DC grids (up to 24V) are considered safe from shock or fire hazard, which allows electricians to install relatively simple wiring, without grounding or metal junction boxes, and without protection against direct contact. [4, 5, 6] This further increases cost savings, and it allows you to install a solar system all by yourself. We demonstrate such a DIY system in the next article, where we also explain how to obtain DC appliances or convert AC devices to DC.

How Much Energy Can Be Saved?

It’s important to note, however, that the energy efficiency advantage of a DC grid is not a given. Energy savings can be significant, but they can also be very small or even turn negative. Whether or not DC is a good choice, depends mainly on five factors: the specific conversion losses in the AC/DC-adapters of all devices, the timing of the "load" (the energy use), the availability of electric storage, the length of the distribution cables, and the power use of the electrical appliances.

Eliminating the inverter results in quite predictable energy savings. It concerns only one device with a rather fixed efficiency (+90% — although efficiency can plummet to about 50% at low load). However, the same cannot be said of AC/DC-adapters. Not only are there as many adapters as there are DC-internal devices, but their conversion efficiencies also vary wildly, from less than 50% for low power devices to more than 90% for high power devices. [6, 7, 8]

Consequently, the total energy loss of AC/DC-adapters can be very different depending on what kind of appliances are used in a building — and how they are used. Just like inverters, adapters waste relatively more energy when little power is used, for instance in standby or low power modes. [8]

The conversion losses in adapters are highest for DVDs/VCRs (31%), home audio (21%), personal computers and related equipment (20%), rechargeable electronics (20%), lighting (18%) and televisions (15%). The electricity losses are lower (10-13%) for more mundane appliances like ceiling fans, coffee makers, dishwashers, electric toasters, space heaters, microwave ovens, refrigerators, and so on. [8].

Lighting and computers (which have high AC/DC-losses) usually make up a great share of total electricity use in offices, shops and institutional buildings. Households have more diverse appliances, including devices with lower AC/DC-losses. Consequently, a DC system brings higher energy savings in offices than in residential buildings.

The largest advantage is in data centers, where computers are the main load. Some data centers have already switched to DC systems, even if they’re not powered by solar energy. Because a large adapter is more efficient than a multitude of small adapters, converting AC to DC at a local level (using a bulk rectifier) rather than at the individual servers, can bring energy savings between 5 and 30%. [6, 9] [10, 11]

The Importance of Energy Storage

If we assume an energy loss of 10% in the inverter and an average loss of 15% for all the AC/DC adapters, we would expect energy savings of about 25% when switching to DC distribution in a solar PV powered building. However, such a significant saving isn’t guaranteed. To start with, most solar powered buildings are grid-connected. They don’t store solar power in on-site batteries, but rely on the grid to deal with surpluses and shortages.

This means that excess solar power needs to be converted from DC to AC in order to send it to the electric grid, while power taken from the grid needs to be converted from AC to DC in order to be compatible with the electrical distribution system of the building. Consequently, in a net-metered solar PV powered building, only loads coincident with solar PV output can benefit from a DC grid.

Early DC power stations had a dynamo for every light bulb. Source unknown.

Once again, this means that the efficiency advantages of a DC system are usually larger in commercial buildings, where most electricity use coincides with the DC output from the solar system. In residential buildings, on the other hand, energy use often peaks in mornings and evenings, when little or no solar power is available.

Consequently, there is only a small advantage to obtain from a DC system in a net-metered residential building, as most electricity will be converted to or from AC anyway. A recent study calculated that a DC system could improve the energy efficiency of a solar-powered, net-metered American home on average by only 5% — the figure is an average for 14 houses across the USA. [12] [13]

Off-Grid Solar Systems

To realize the full potential of a DC grid, especially when it concerns a residential building, we need to store solar energy in on-site batteries. In this way, the system can store and use power in DC form. Energy storage can happen in an off-grid system, which is fully independent of the grid, but adding some battery storage to a net-metered building also improves the advantage of a DC system. However, energy storage adds another type of energy loss: the charging and discharging losses of the batteries. The round-trip efficiency for lead-acid batteries is 70-80%, while for lithium-ion it’s about 90%.

Exactly how much energy can be saved with on-site battery storage again depends on the timing of the load. Electricity used during the day — when the batteries are full — doesn’t involve any battery charging and discharging losses. In that case, the energy savings of a DC system can be 25% (10% for eliminating the inverter and 15% for eliminating the adapters).

However, electricity used after sunset lowers the energy savings to 15% for lithium-ion batteries and between -5% and +5% for lead-acid batteries. In reality, electricity will probably be used both before and after sunset, so that efficiency improvements will be somewhere between those extremes (-5% to 25% for lead-acid, and 15-25% for lithium-ion).

Kensington Court Station: steam engine, dynamo and batteries. Source: Central-Station Electric Lighting, Killingworth Hedges, 1888.

On the other hand, battery storage brings an additional advantage: there are less or — in a totally independent system — no additional energy losses for the long-distance transmission and distribution of AC electricity. These losses vary a lot depending on the location. For example, average transmission losses are only 4% in Germany and the Netherlands, but 6% in the US and China, and between 15 and 20% in Turkey and India. [14] [15]

If we add another 7% of energy savings due to avoided transmission losses, an off-grid DC system can bring energy savings between 2% and 32% for lead-acid batteries, and between 22% and 32% for lithium-ion batteries, depending on the timing of the load.

Assuming 50% energy use during the day and 50% energy use during the night, we arrive at a gain of 17% for an off-grid system using lead-acid batteries, and 27% for lithium-ion storage. This means that electricity use can be met with a solar system that is one-fifth to one-third smaller, respectively. Total cost savings will remain a bit larger, because we still don’t need an inverter, and installation costs are lower or non-existent.

Unfortunately, introducing on-site electricity storage raises capital costs again, because we need to invest in batteries. This will negate the cost advantage we obtained through in choosing a DC system. The same goes for the energy invested in the production process: an off-grid DC system requires less energy for the manufacturing of solar panels, but it instigates at least as much energy use for the manufacturing of batteries.

However, we should compare apples to apples: a DC off-grid solar system is cheaper and more energy efficient than a AC off-grid system, and that’s what counts. The life cycle analyses of net-metered solar systems do not represent reality, because they ignore an essential component of solar energy systems.

Cable losses

There’s one more important thing to consider, though. As we have seen, power loss due to resistance is proportional to the square of the current. Consequently, low-voltage DC grids have relatively high cable losses within the building. There are two ways in which cable losses can make a choice for a DC system counterproductive. The first is the use of high power devices, and the second is the use of very long cables.

Voltage regulation in early power plant. Source unknown.

The energy loss in the cables equals the square of the current (in ampère), multiplied by the resistance (in ohm). The resistance is determined by the length, the diameter, and the conducting material of the cables. A copper wire with a cross section of 10 mm2, distributing 100 watts of power at 12 V (8.33 A) over a distance of 10 metres yields an acceptable energy loss of 3%. However, with a cable length of 50 metres, energy loss becomes 16%, and at a length of 100 metres, the energy loss adds up to 32% — enough to negate the efficiency advantages of a DC grid even in the most optimistic scenario.

The relatively high cable losses also limit the use of high power appliances. If you want to run a 1,000 watt microwave on a 12V DC grid, the energy losses add up to 16% with a cable length of only 1 metre, and jump to 47% with a cable length of 3 metres.

Obviously, a low-voltage DC grid is not suited to power devices such as washing machines, dish washers, vacuum cleaners, electric cookers, electric ovens, or warm water boilers. Note that power use and not energy use is important in this regard. Energy use equals power use multiplied by time. A refrigerator uses much more energy than a microwave, because it’s on 24 hours per day, but its power use can be small enough to be operated on a DC grid.

Cable losses also limit the combined power use of low power devices. If we assume a 12V cable distribution length of 12 metres, and we want to keep cable losses below 10%, then the combined power use of all appliances is limited to about 150 watts (8.5% cable loss). For example, this allows the simultaneous use of two laptops (20 watts of power each), a DC refrigerator (45 watts), and five 8 watt LED-lamps (40 watts in total), which leaves another 25 watts of power for a couple of smaller devices.

How to Limit Cable Losses

There are several ways to get around the distribution losses of a low-voltage DC system. If it concerns a new building, its spatial layout could significantly limit the distribution cable length. For example, Dutch researchers managed to reduce total cable length in a house down from 40 metres to 12 metres. They did this by moving the kitchen and the living room (where most electricity is used) to the first floor, just below the roof (where the solar panels are), while moving the bedrooms to the ground floor. They also clustered most appliances in the central part of the building, right below the solar panels (see the illustration below). [16]

Another way to reduce cable losses is to set up several independent solar systems per one or two rooms. This might be the only way to solve the issue in a larger, existing building that’s designed without a DC system in mind. While this strategy implies the use of extra solar charge controllers, it can greatly reduce the cable losses. This approach also allows the power use of all appliances to surpass 150 watts.

A third way to limit cable losses is to choose a higher voltage: 24 or 48V instead of 12V. Because the energy losses increase with the square of the current, doubling the voltage from 12 to 24V makes cable losses 4 times smaller, and switching to 48V decreases them by a factor of sixteen. This approach also allows the use of higher power devices and increases the total power that can be used by a DC system. However, higher voltages also have some disadvantages.

First, most low-voltage DC appliances currently on the market operate on 12V, so that the use of a 24 or 48V DC network involves the use of more DC/DC-adapters, which step down the voltage and also have conversion losses. Second, higher voltages (above 24V) eliminate the safety advantages of a DC system. In data centers and offices, as well as in the American residential buildings in the study mentioned earlier, DC electricity is distributed throughout the building at 380V, but this requires just as stringent safety measures as with 110V or 220V AC electricity. [17]

Slow Electricity

Shortening cable length or doubling the voltage to 24V still doesn’t allow for the use of high power devices like a microwave or a washing machine. There are two ways to solve this issue. The first is to install a hybrid AC/DC-system. In this case, a DC grid is set up for low power devices, such as LED-lights (< 10 watt), laptops (< 20 watt), a television (30-90 watt) and a refrigerator (<50 watt), while a separate AC grid is set up for high power devices. This is the approach for homes and small offices that’s promoted by the EMerge Alliance, a consortium of manufacturers of DC products, which devised a standard for a 24V DC / 110-220V AC hybrid system. [18]

Late 19th century, the only electric load in households was lighting.

Low power devices are (on average) responsible for 35-50% of total electricity use in a home. Even in the best-case-scenario (50% of the load), a hybrid system halves the energy efficiency gains we calculated above, which leaves us with an energy savings of only 8.5% to 13.5%, depending on the types of batteries used. These figures will be lower still due to cable losses. In short, a hybrid AC/DC system brings rather small energy savings, that could easily be erased by rebound effects.

The second way to solve the problem of high power devices is simply not to use them. This is the approach that’s followed in sailboats, motorhomes and caravans, where a supporting AC distribution system is simply not an option. This is the most sustainable solution to the limits of DC power, because in this case the choice for DC also results in a reduction of energy demand. Total energy savings could thus become much larger than the 17-27% calculated above, and then we finally have a radically better solution that could make a difference.

Obviously, this strategy implies a change in our way of life. It would mean that electricity is used only for lighting, electronics and refrigeration, while non-electric alternatives are chosen for all other appliances. Not coincidentally, this is quite similar to how DC grids were operated in the late nineteenth century, when the only electric load was for lighting — first arc lamps and later incandescent bulbs.

Thus, no dishwasher, but doing the dishes by hand. No washing machine, but doing the laundry in a laundromat or with a manually operated machine. No tumble dryer, but a clothes line. No convenient and time-saving kitchen appliances like electric kettles, microwaves and coffee machines, but a traditional cooking stove operated by (bio)gas, a solar cooker, or a rocket stove. No vacuum cleaner, but a broom and a carpet-beater. No freezer, but fresh ingredients. No electric warm water boiler, but a solar boiler and a small wash at the sink if the sun doesn’t shine. No electric car, but a bicycle.

To figure out what’s possible, we’re converting Low-tech Magazine’s headquarters into an off-grid 12V DC system — more about that in the next post.

Written by Kris De Decker. Edited by Jenna Collett.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Power Water Networks

- How to Build a Low-tech Internet

- Off-grid: How Sustainable is Stored Sunlight

- Solar PV Power: Why Location Matters

- Back to Bascis: Direct Hydropower

- Bike Powered Electricity Generators are not Sustainable

- How to Make Everything Ourselves: Open Modular Hardware

SOURCES & NOTES

[1] There is an analogy with hydraulic power: electric voltage corresponds to water pressure, while electric current corresponds to water flow. The invention of the hydraulic accumulator in the 1850s allowed higher water pressure and thus efficient transportation of water power over long distances.

[2] Study and simulation of a DC microgrid with focus on efficiency, use of materials and economic constraints (PDF), Simon Willems & Wouter Aerts, 2013-14

[3] Direct Current supply grids for LED lighting, LED professional

[4] DC microgrids scoping study: estimate of technical and economic benefits, Scott Backhaus et al., March 2015

[5] DC microgrids and the virtues of local electricity, Rajendra Singh & Krishna Shenai, IEEE Spectrum, 2014

[6] Comparison of cost and efficiency of DC versus AC in office buildings (PDF), Giuseppe Laudani, 2014

[7] Edison’s Revenge, The Economist, 2013

[8] Catalog of DC appliances and power systems, Karina Garbesi, Vagelis Vossos and Hongxia Shen, 2011

[9] DC building network and storage for BIPV integration, J. Hofer et al., CISBAT 2015, 2015

[10] However, DC power in data centers will not bring us a less energy-hungry internet — on the contrary.

[11] Also note that the efficiency of AC/DC adapters could be improved in a significant way, especially for low power devices. Many "wall warts" are needlessly wasteful because manufacturers of electric appliances want to keep costs down. If this would change, for example because of new laws, the advantage of switching to a DC grid would become smaller.

[12] Energy savings from direct-DC in US residential buildings, Vagelis Vossos et al, in Energy and Buildings, 2014

[13] In this study, the buildings use a combination of 24V DC for low power loads, and 380V DC for high-power devices and for distributing DC power throughout the house to limit cable losses.

[14] Electric power transmission and distribution losses (% of output), World Bank, 2014

[15] Rural areas usually have higher losses than urban areas, and a lone subdivision line that radiates out into the countryside can introduce very high losses.

[16] Concept for a DC low voltage house (PDF), Maaike Friedeman et al, Sustainable building 2002 conference

[17] A last — and rather desperate — way to lower distribution losses is to use thicker cables. The resistance in electric wires can be decreased not only by shortening the cables, but also by increasing their diameter (diameter here refers to the copper core). For example, if we would use 100 mm2 instead of 10 mm2 cables, we can have cables that are ten times longer for the same energy loss. Distributing 12V DC electricity across 100 metres of cable would yield an energy loss of only 3%. One problem with this approach is that the costs of electric cables increase linearly with the diameter. One metre of 100 mm2 cable will cost you about 50 euro, compared to 5 euro for a 10 mm2 cable. Sustainability also suffers because the higher use of copper has a significant environmental cost. Thick cables are heavy and less manageable, too. Thanks to Herman van Munster en Arie van Ziel for making this clear.

[18] Our standards, Merge Alliance, retrieved April 2016