Presently Americans wait with bated breath, watching sales numbers and unemployment statistics, grasping for signs that an economic recovery is underway. We search for signals that indicate we’re growing, that there will be a job for everyone who wants one, and that the United States will resume the prosperity and standing in the world it once had.

We wait in vain.

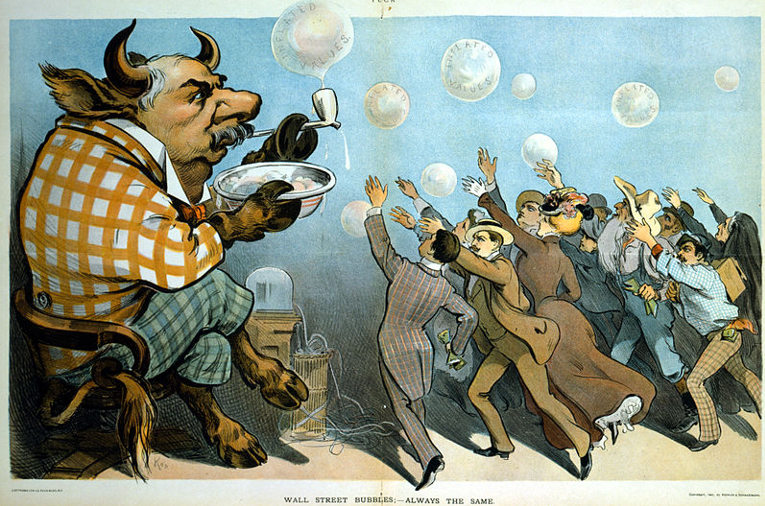

Sometimes it takes a cartoon character to show the absurdity of our global economic system (click to play video)

The economy isn’t coming back. On the contrary, it’s a patched-together mess on its way to the crapper. Though the Obama administration might crow about a tepid recovery, even today’s insufficient economy is itself a lie, propped up by governments printing money to buy their own bonds and simulate growth. The Dow ascends to ever more lofty heights, and yet few believe it’s tied to improving conditions for regular people. China, the economic engine of the world, is now slowing precipitously, and experiencing serious market declines and confidence problems. Europe is an economic mess, and when the EU eventually implodes (it really is a when and not an if), it will send shocks through the rest of our globalized world.

To try and remedy our situation, every government is of course promoting growth. We continue to push the lie that we’ve all internalized but have never spoken: that we could have infinite growth on a finite planet. Expecting infinite from the finite is an absurdist proposition, one that falls apart for the same reason the world economy has stalled: resource constraints. It might seem preposterous to talk about resource constraints, when we in the Western world are surrounded by endless abundance. After all, don’t we have the choice of ten different kinds of kitchen sponges, and 20 types of diet soda?

Yet if you can look past the bounty of the supermarket shelf, there are really dire resource shortages advancing from all sides. For example:

OIL

OIL

Oil is the lifeblood of modern civilization…and it’s running out. The world’s biggest fields are running dry, leaving humanity to scrape the bottom of the barrel with high effort-low reward energy options like Tar Sands and fracking. Peak Oil is and always has been a real thing, so if you’re unfamiliar with the concept I’d recommend a quick introduction.

WATER

WATER

Oil may be civilization’s lifeblood, but water is life itself — and it too is becoming scarce as sources are ravaged by climate change and rampant overuse. Water will be more valuable than oil in the future, and already conflicts over water rights are common. You might shrug and assume I’m talking only of sources in arid regions like the Middle East and North Africa, but even within the United States the water wars have begun.

LAND

LAND

Right now rich countries are buying up huge tracts of land in poorer countries, primarily to grow food and ship it back home. These countries, of which China is the most prolific, need this extra production because as their population and consumption levels skyrocket, they are increasingly unable to feed their people. Exacerbating the problem is the fact that humanity is pissing away its topsoil, making much of Earth’s arable land worthless.

Oil, water, land…these are the basic building blocks of modern civilization, and all three are in serious jeopardy. Everyone knows the economy is terrible right now, yet for each person you’d no doubt get a different opinion about the cause — lazy people, corporate abuses, excess regulation, automation, corruption, partisanship in Washington, the list goes on and on. But step back for a moment and consider the fact that what’s unfolding is much more fundamental: our output is so low because our inputs are dwindling. Beyond even the fundamental inputs outlined above, there are dozens of other key shortages contributing to our economic woes like phosphorus (fertilizer), rare earth metals (electronics), fish, and copper. All of those are legitimate crises in their own right; taken together, it’s the death knell for a growth-based economy.

A brief interview with author Richard Heinberg, who explains this stuff much better than I do click to play video (7:20)

So I put to you again: the economy we knew isn’t coming back. As our resources run out, prices will skyrocket and we will no longer be able to afford those that come from far-flung places after winding their way through an energy-intensive distribution system. In a world where every calorie of food you consume requires 10 calories of energy to produce, package, and transport, your Chilean Sea Bass and your Saudi Arabian oil will share the same fate.

But though our growth economy cannot survive, if we are diligent and inventive a new economy may bloom in its stead. The future of the world is local: economic inputs like food and energy will be produced in your local community. Prosperity will be found within worker cooperatives, which often perform much better than traditional businesses in times of economic turmoil. Things will not be easy, and there are no silver bullets here. Saying goodbye to the growth paradigm will be scary and strange, because it’s really all we’ve ever known. But I feel confident that with grit, determination and a bit of luck we’ll find our way through to something better on the other side.