The Long Descent

The Long Descent

A User’s Guide to the End of the Industrial Age

By John Michael Greer

Americans are expressing deep concern about US dependence on petroleum, rising energy prices and the threat of climate change. Unlike the energy crisis of the 1970s, however, there is a lurking fear that, now, the times are different and the crisis may not easily be resolved.

The Long Descent examines the basis of such fear through three core themes:

- Industrial society is following the same well-worn path that has led other civilizations into decline, a path involving a much slower and more complex transformation than the sudden catastrophes imagined by so many social critics today.

- The roots of the crisis lie in the cultural stories that shape the way we understand the world. Since problems cannot be solved with the same thinking that created thyem, these ways of thinking need to be replaced with others better suited to the needs of our time.

- It is too late for massive programs for top-down change; the change must come from individuals.

Hope exists in actions that range from taking up a handicraft or adopting an “obsolete” technology, through planting an organic vegetable garden, taking charge of your own health care or spirituality, and building community.

Focusing eloquently on constructive adaptation to massive change, this book will have wide appeal.

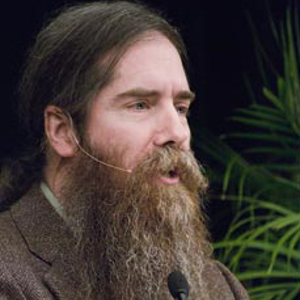

John Michael Greer is a certified Master Conserver, organic gardener and scholar of ecological history. The current Grand Archdruid of AODA, his widely-cited blog, The Archdruid Report (www.thearchdruidreport.blogspot.com) deals with peak oil, among other issues. He lives in Ashland, Oregon.

Chapter 2: The Stories We Tell Ourselves

Excerpt: pages 50-55.

Knowing Only One Story

One of the things that makes our culture’s reliance on the utopian myths of progress and apocalypse so problematic as we approach the end of the age of cheap energy is that both narratives claim to explain the entire universe. Universal claims of this sort have become popular in recent centuries, but from a wider historical perspective, stories that claim to be the answer to everything are something of a novelty. Traditional cultures around the world, in fact, have a very large number of stories, and much of the education received by young people in those cultures consists of sharing, learning, and thinking about those stories.

The stories handed down in oral cultures aren’t simply entertainment, any more than are the stories we tell ourselves about the universe today. Stories are probably the oldest and most important of all human tools. Human beings think with stories, fitting what William James called the “blooming, buzzing confusion” of the universe around us into narrative patterns that make the world make sense. We use stories to tell us who we are, what the world is like, and what we can and can’t do with our lives. Every culture has its stories, and if you pay careful attention to the stories a culture tells, you can grasp things about the culture that nothing else will teach you.

One of the most striking things about old stories – stories of traditional cultures – is that no two of them have the same moral. If you were born in an English-speaking culture, for example, you likely grew up with the last remnant of England’s old stories in the form of fairy tales that put different people in different situations, with very different results. Sometimes violating a prohibition brought success (think “Jack and the Beanstalk”), but sometimes it brought disaster (“Sleeping Beauty”). Sometimes victory went to the humble and patient (“Cinderella”), but sometimes it went to the one who had the chutzpah to dare the impossible (“Puss in Boots”). Common themes run through the old stories, of course, but they never take the same shape twice. Those differences are a source of great power. If you have a wealth of different stories to think with, odds are that whatever the world throws at you, you’ll be able to find a narrative pattern that makes sense of it.

Over the last few centuries, though, the multiple-narrative approach of traditional cultures has given way, especially in the industrial West, to a way of thinking that privileges a single story above all others. Think of any currently popular political or religious ideology, and you’ll likely find at its center the claim that one and only one story explains everything in the world. For fundamentalist Christians, it’s the story of Fall and Redemption ending with the Second Coming of Christ. For Marxists, it’s the story of dialectical materialism ending with the dictatorship of the proletariat. For believers in any of the flotilla of apocalyptic ideologies cruising the waterways of the modern imagination, it’s another version of the same story, with different falls from grace ending in redemption through different catastrophes. For rationalists, neoconservatives, most scientists, and many other people in the developed world, the one true story is the story of progress. The political left and right each has its own story; and the list goes on. From the perspective of traditional cultures, believers in these ideologies are woefully undereducated, since for all practical purposes, they know only one story.

This modern habit of knowing only one story has certain predictable results. One of these is that the story itself becomes invisible to those who believe in it. From their perspective, their story isn’t a story, it’s simply the way things are, and the fact that it copies other versions of the same story is irrelevant, since their story is true and the others aren’t. Often the story becomes so much a part of everyday thinking that it vanishes from sight entirely, becoming a presupposition that may never be stated or even noticed by those who build their lives around it. The myth of progress, a sterling example, has become so pervasive nowadays that few people notice how completely it dominates current thinking about the future. Speaking about historians of his own time who embraced the mythology of progress, the great 20th century historian Arnold Toynbee wrote:

The difference between these post-Christian Western historians and their Christian predecessors is that the moderns do not allow themselves to be aware of the pattern in their minds, whereas Bossuet, Eusebius, and Saint Augustine were fully conscious of it. If one cannot think without mental patterns – and, in my belief, one cannot – it is better to know what they are; for a pattern of which one is unconscious is a pattern that holds one at its mercy.9

While the story itself may become invisible, its implications are anything but, and this leads to the second symptom of knowing only one story: the certainty that whatever problem comes up, it has one and only one solution. For fundamentalist Christians, no matter what the problem, the solution is surrendering your will to Jesus (or, more to the point, to the guy who claims to be able to tell you who Jesus wants you to vote for). For Marxists, the one solution for all problems is proletarian revolution. For neoconservatives, it’s the free market. For scientists, it’s more scientific research and education. For Democrats, it’s electing Democrats; for Republicans, it’s electing Republicans, and so on.

What makes this fixation on a single solution so problematic is that the universe is what ecologists call a complex system. In a complex system, feedback loops with unexpected consequences make a mockery of simplistic attempts to predict effects from causes. No one solution will effectively respond to more than a small portion of the challenges the system can throw at you. This leads to the third symptom of knowing only one story: repeated failure.

Recent economic history offers a good example. For the last two decades, free-market advocates in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have been pushing a particular set of economic policies on governments and economies around the world, insisting that these are the one and only solution to every economic ill. Everywhere those policies have been fully implemented, the result has been economic and social disaster – think East Asia in the late 1980s, or Russia and Latin America in the 1990s – and every one of the countries devastated by the results has returned to prosperity only after junking the policies in question.10 None of this has stopped the free market’s true believers from continuing to press forward toward the imaginary Utopia their story promises them.

For those who know plenty of stories, and know how to think with them, the complexity of the universe is easier to deal with, because they have a much better chance of being able to recognize what story the universe seems to be following, and act accordingly. Those who don’t know any stories at all – if such improbable beings actually exist – may still get by; even though they don’t have the resources of story-wisdom to draw on, they may still be able to judge the situation on its own merits and act accordingly, because a lack of stories at least offers some hope of flexibility.

Those who only know one story, though, and are committed to the idea that the world makes sense if and only if it’s interpreted through the filter of that one story, are stuck in a rigid stance with no options for change. Much more often than not, they fail, since the complexity of the universe is such that no single story makes a useful tool for understanding more than a very small part of it. If they can recognize this and let go of their story, they can begin to learn. If you’ve gotten your ego wrapped up in the idea that you know the one and only true story, on the other hand, and you try to force the world to fit your story rather than allowing your story to change to fit the world, the results will not be good.

This leads to the fourth symptom of knowing only one story: rage. The third symptom, failure, can be a gift because it offers the opportunity for learning, but if the gift is too emotionally difficult to accept, the easy way out is to take refuge in anger. When we get angry with people who disagree with us about politics or religion, I’m coming to think, very often what really angers us is the fact that our preferred story doesn’t fit the universe everywhere and always, and those who disagree with us simply remind us of that uncomfortable fact.

Plenty of pundits, and many others as well, have commented on the extraordinary level of anger that surges through America these days. From talk radio to political debates to everyday conversations, dialogue has given way to diatribe across the political spectrum. It’s unlikely to be a coincidence that this has happened over a quarter century when the grand narratives of both major American political parties failed the test of reality. The 1960s and 1970s saw the Democrats get the chance to enact the reforms they wanted; the 1980s and the first decade of the 21st century saw the Republicans get the same opportunity. Both parties found themselves stymied by a universe that obstinately refused to play along with their stories, and both sides turned to anger and scapegoating as a way to avoid having to rethink their ideas.

That habit of rage isn’t going to help us, or anyone, as we move toward a future that promises to leave most of our culture’s familiar stories in tatters. As we face the unwelcome realities of the limits to growth, clinging to whatever single story appeals to us may be emotionally comforting in the short term, but it leads to a dead end familiar to those who study the history of extinct civilizations. Learning other stories, and learning that it’s possible to see the world in many ways, is a more viable path – but it can be a challenging one that many people can’t or won’t take.

Chapter 5: Tools for the Transition

Excerpt: pages 168-172.

One of the most hopeful features of this side of our predicament is that the revitalization of old technologies can be done successfully by individuals working on their own. It’s precisely those technologies that can be built, maintained, and used by individuals that formed the mainstay of the economy in the days before cheap, abundant energy made a global economy seem to make sense. These same technologies – if they’re recovered while time and resources still permit – can make use of the abundant salvage of industrial civilization, help cushion the descent into the deindustrial future, and lay foundations for the sustainable cultures that will rise out of the ruins of our age.

Another practical example shows how this can work. Some time ago, after mulling over the points just mentioned, I started looking into the options for climbing down the ladder a rung or two in the field of practical mathematics. The slide rule was an obvious starting place. A few inquiries revealed that most of my older friends still had a slipstick or two gathering dust in a desk drawer, and not long afterward I found myself being handed a solid aluminum Pickett N903-ES slide rule in mint condition. The friend who gave it to me is getting on in years and has a short white beard, and though he looks more like Saint Nicholas than Alec Guinness, I instantly found myself inside one of the fantasies burned into the neurons of my entire generation:

“This,” Obi-wan Kenobi tells me, “is your father’s slide rule.” I take the gleaming object in one hand, my gaze never leaving his face. “Not so wasteful or energy-intensive as a calculator,” he says then. “An elegant instrument of a more sustainable age.” I press my thumb against the cursor, and…

Well, no, a blazing blue-white trigonometric equation didn’t come buzzing out of the business end, and of course that’s half the point. The slide rule is an extraordinarily simple, low-tech device that lets you crunch numbers at what, at least in pre-computer terms, was a very respectable pace. Even by current standards it’s not slow. I’ve only begun to learn the ways of the Force, so to speak, but I can easily multiply and divide on my Pickett as fast or faster than I can punch buttons on a calculator.

Beyond its practical uses, however, the slide rule has more than a little to teach about what sustainable technology looks like. It’s quite literally pre-industrial technology – the basic principle was worked out in 1622 by Rev. William Oughtred, though it took many more years of experimentation to produce the handy ten- inch device with multiple scales that played so important a role in 19th and 20th century science and engineering. This simple device crunched most of the numbers that put human footprints on the moon. Set a slide rule side by side with an electronic calculator and certain points stand out.

First, a slide rule is durable. By this I don’t simply mean that you have to use more force to break a slide rule than a pocket calculator, though this is generally true. More important is the fact that a pocket calculator has a limited shelf life. Over fairly modest time spans, batteries go dead, memory and processing chips break down, and plastics depolymerize into useless goo. Even the cheap plastic slide rules once mass-produced for schoolchildren will outlast most pocket calculators, and a good professional model can stay in working order for something close to geological time.

Second, a slide rule is independent. You don’t need to rely on any other technology to make it work or to do something useful with the output. Pocket calculators depend on a certain level of battery technology to work, though admittedly this puts them toward the independent end of the spectrum. By contrast, think of the number and extent of the technological systems needed to keep a car or an Internet terminal functioning and useful.

Third, a slide rule is replicable. If you have one, it doesn’t take advanced industrial technology to make another, or a thousand more; a competent cabinetmaker with hand tools and a good eye can produce them as needed. Making a pocket calculator, by contrast, demands a mastery of dozens of extraordinarily complex and energy-intensive technologies: clean rooms with nanoparticle-free air, solvent chemistry, and manufacture of monomolecular metallic films are but a few. Once these technologies can no longer be sustained – a dead certainty in the deindustrial age – pocket calculators become a nonrenewable resource. Slide rules remain viable as long as something like the technology of Oughtred’s time remains available.

Fourth, a slide rule is transparent. By this I mean that it’s easy to work out the principles that make it function from the device itself. This is crucial, because a transparent technology can communicate much more than its own output.

Imagine for a moment that the deindustrial age turns out much more severe than we have reason to expect, and nearly all mathematical knowledge gets lost.A thousand years from now, a surviving slide rule ends up in the hands of a scholar who has laboriously learned how to read ancient numbers and has learned all the arithmetic known in her time. A few minutes of fiddling would show her how the C and D scales can be used to multiply and divide numbers, and a few more would reveal that the A scale shows the squares of corresponding numbers on the D scale. Once she realizes that each scale shows a different mathematical operation, the device itself becomes a mathematical Rosetta stone that can teach her all about fractions, decimals, squares and square roots, cubes and cube roots, reciprocals, and logarithms, because all the mathematical relationships are right there in plain sight.

If our imaginary scholar gets an ancient pocket calculator instead, none of this happens, because the algorithms that make a calculator work are hidden away in its circuitry. Even if the thing still works, it’s a black box that spits out numbers, and the relationships between the numbers would have to be worked out the hard way, by trial and error. For that matter, how would our future scholar realize that the calculator was a calculator rather than, say, a remote control or some other enigmatic ancient relic?

Science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke unknowingly pointed out one of the potential long-term weaknesses of our present technology in his famous Third Law: “Every sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”8 What makes one technology more or less advanced than another is a subtler question than it may appear at first glance, but Clarke’s point remains valid: once a technology becomes complicated enough that it loses transparency, it can be very hard to recognize the technology for what it is – and very easy to turn it into a stage property for ritual use. A number of today’s technologies have already become ritual props in industrial society’s mostly unacknowledged ceremonial life, and that process could accelerate drastically as education levels decline and technologies become rare.

The effects of Clarke’s law thus have to be dealt with if the technologies we pass on to the deindustrial future are going to be of value to anyone. For that matter, all four of the principles suggested by the humble slide rule – durability, independence, replicability, and transparency – make good criteria for any technology meant to outlast the industrial age. Too many of the technologies currently being touted as answers to peak oil fail one or more of these tests, and many fail all four. As the world begins to move beyond debating the fact of fossil fuel depletion and starts tackling the challenges of planning for a difficult future, a careful study of potential technologies in something like the terms I’ve outlined may be a good place to start.9

Scores of other technologies, skills, and traditions of high value to a low-energy future can be found with a little searching. Consider the haybox or fireless cooker, a container full of insulating material with a well in the center to hold a pot of food. Hay- boxes were a standard piece of kitchen equipment in the industrial world a century ago; if your great-grandmother lived in Europe or North America she very likely had one. She brought food to a boil, popped it into the haybox, and left it there to cook by residual heat, saving most of the fuel she would have needed to cook the same dish on the stove.10 Haybox technology could make a future of energy shortages much more livable, but only if it’s brought out of museums and put back into circulation before knowledge about it is lost.